Confronting Carbon Pollution

By Molly Moore

Six months after declaring “climate change is a fact,” in his State of the Union address, President Obama prepared to unveil what The New Yorker calls “the policy centerpiece of his second term.” The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency guidelines that he was poised to announce at press time will put in motion state and federal policies that could determine whether the nation moves toward climate security and cleaner sources of power or sits on the sidelines as the seas rise.

Climate change is expected to decrease water availability in the Southeast. Above, drought conditions transform Fontana Lake, N.C., in summer 2007. Photo by Ryan Rasmussen, courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

“When our children’s children look us in the eye and ask if we did all we could to leave them a safer, more stable world, with new sources of energy,” Obama told Congress and the nation, “I want us to be able to say yes, we did.”

The Case Against Carbon

The EPA currently limits emissions of air pollutants such as mercury and other pollutants associated with producing electricity, but as the agency moves to regulate the amount of carbon dioxide that existing coal-fired power plants can release into the atmosphere, it is grappling with arguably its most significant challenge yet.

Carbon dioxide is a fundamental building block of life on Earth, but it’s also king among the gases that have an overall warming effect on the planet. These greenhouse gases act somewhat like the plastic shield on a greenhouse, holding the heat from the sun’s rays close to Earth instead of letting it bounce freely back into space. Of the greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activities in the U.S., carbon dioxide comprises 82 percent. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today is about 40 percent greater than it was in the mid-1700s before the industrial era began. Essentially, the greenhouse barrier is getting thicker and the Earth is getting warmer.

Global scientific consensus links the sharp rise in carbon to a host of climate projections. According to the National Climate Assessment, a report released in May by a consortium of experts assembled by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, prominent impacts in the Southeast will include sea level rise, more extreme heat events and decreased water availability.

The federal government began to seriously connect carbon dioxide emissions to climate change in the late 1970s, but there has been scant political action. In 2009, President Obama pledged that the United States would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 if other economically powerful countries made similar commitments. When the Senate failed to ratify the “cap and trade” carbon bill in 2010, the president was prompted to pursue a method of addressing climate change that relies on executive powers instead of Congress.

The EPA wasn’t always in favor of regulating carbon dioxide. In 2007, under President George W. Bush, the EPA attempted to deny its authority to address greenhouse gases. But the Supreme Court disagreed and ruled that the agency would be obligated to regulate greenhouse gases if it determined that the pollutants endangered public health and welfare. When the Obama administration began in 2009, then-EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson declared that greenhouse gases did pose risks to the public.

“The science on whether or not these gases are pollutants is clear,” Jackson said during a 2009 interview with Time magazine. “As the endangerment finding says, in both magnitude and probability climate change is an enormous problem.”

Those risks, according to the National Climate Assessment, include “increasingly frequent, intense, and longer-lasting extreme heat, which worsens drought, wildfire, and air pollution risks; increasingly frequent extreme precipitation, intense storms, and changes in precipitation patterns that lead to drought and ecosystem changes; and rising sea levels that intensify coastal flooding and storm surge.” Summertime levels of harmful ground-level ozone could rise by as much as 70 percent by 2050 if emissions are left unchecked, reports a study published this May in Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. Analysts project that humans will contend with troubles such as escalating asthma and allergy rates, more heat-related illness and death, a rise in insect-borne illnesses such as Lyme Disease, and challenges to the food system due to drought.

With a clear link established between public health and safety and climate change, the EPA began limiting greenhouse gas emissions in 2011 by finalizing fuel efficiency standards for heavy-duty trucks and buses. The agency also said it would focus on regulating the largest industrial polluters — those responsible for roughly 70 percent of national greenhouse gas emissions — and avoid limiting small businesses. With fossil-fuel power plants responsible for 40 percent of nationwide carbon dioxide emissions, it was clear that the electricity sector would be affected.

In September 2013 the EPA announced its intention to limit the amount of carbon dioxide that can be released by new and current power plants.

Policy Prescriptions

The EPA’s authority to regulate both new and existing power plants leans on a section of the Clean Air Act, but the act prescribes different ways for handling future versus current facilities.

The agency is given more top-down authority when it comes to new facilities and is able to set federal carbon emissions standards for all new power plants. Last January the EPA released its proposed standards for new power plants — the public was able to comment on the draft standards until early May, and the rules are scheduled to be finalized this coming winter.

Duke Energy’s Riverbend Steam Plant in Gaston County, N.C., was retired in April 2013; the utility said the plant, which began operating in 1929, was rarely used. Political analysts suggest that outlining a strong plan for reducing its own carbon emissions could give the United States added leverage at the 2015 international climate change conference in Paris. Photo by Sandra Diaz

By capping the amount of carbon dioxide a coal-fired power plant can emit at 1,100 pounds per megawatt-hour, the rules are pushing utilities to instead use zero-emission renewables, energy efficiency improvements or natural gas. Utilities could also deploy carbon capture and storage technology to capture carbon emissions and contain them underground. The new technology, however, has not been used on a commercial scale; coal industry supporters say it’s too expensive and environmental advocates counter that utilities just haven’t had any incentives to make the switch.

Unsurprisingly, coal and utility groups are decrying the carbon standards for new power plants as an attack on the electricity industry, while environmental and public health organizations are applauding the move. “The whole point of these regulations is to discourage carbon, to make it unprofitable to create electricity with a lot of carbon,” David Doniger of the Natural Resources Defense Council said on The Diane Rehm Show, “And so we’ll see technologies that allow companies, electric utilities to squeeze more energy out, more electricity out with less carbon [polluting the air].”

As the standards for new power plants move forward, the process for existing ones is just beginning. Because it can be more expensive to change the way existing facilities work, the EPA has a different, more flexible method for devising new air pollution standards for already-established power plants. In this scenario, regulators first issue general guidelines that outline what the end carbon-reduction goals should be. Once those goals are established, the states devise their own plans for meeting the targets and submit their plans to the EPA for approval.

Obama himself is expected to announce the EPA’s proposed guidelines for carbon emissions from existing power plants at the beginning of June. The public will have until September to comment on the proposal, and by June 2015 the EPA will finalize its guidelines. States will have until June 30, 2016, to submit their plans for achieving the needed reductions, and the EPA will have until the end of 2016 to review each state’s plan. If all goes according to the administration’s agenda, by the time Obama’s term ends in January 2017 the nation will be on its way to lower carbon emissions — provided the rules withstand the lawsuits that industry groups and coal-friendly states are likely to file.

Carbon Standards and the Southeast

Regional supporters of energy efficiency and renewable energy, along with public health and environmental advocates, are watching closely to see how the EPA guidelines influence the Southeast’s overall energy mix.

Mary Shaffer Gill, president of the Tennessee Solar Energy Industries Association and vice president of Aries Energy, LLC, says the EPA guidelines are coming at an opportune time, as solar industry groups are talking with the Tennessee Valley Authority about how the federal utility can integrate more solar power into its energy portfolio. “The next two years are going to be very critical in developing long-term solar policy and bigger-picture lofty goals, making sure we’re seeing positive policy for our industry,” she says.

At the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance, Policy Associate Abby Schwimmer says that investing in energy efficiency puts states in a position of strength and preparedness, regardless of how the carbon rule and other federal regulations pan out.

Public health officials are also watching. Among other ills, carbon emissions can be directly and indirectly tied to North Carolina’s high rate of pediatric asthma, says Gayatri Ankem of Medical Advocates for Healthy Air, a branch of the advocacy organization Clean Air Carolina. Citing the host of health consequences associated with higher ozone and pollen levels, changing weather patterns, and more severe storms, Ankem says that addressing carbon emissions will strike at the core of these problems.

Despite the known health concerns, those most at risk from poor air quality and the impacts of climate change have been underrepresented in the policy-making process, says Jacqui Patterson, director of the NAACP Climate Justice Initiative.

Nearly 78 percent of African-Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant, she says, and African-Americans are hospitalized for asthma at a rate three times as often. She notes that low-income communities and communities of color near power plants pay a cost for “cheap” energy in terms of attention problems linked to lead exposure, asthma attacks, and lost work and school days due to poor air quality.

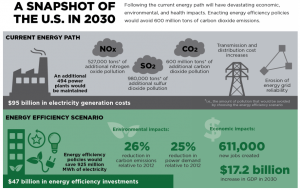

Click to enlarge // The most affordable way for states to reduce carbon emissions is simply by using electricity more efficiently, according to advocates such as the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. By pursuing four energy-efficiency policies such as adopting stricter national building codes and setting state energy efficiency targets, the group reports that “an emissions standard set at 26% below 2012 levels can be achieved at no net cost to the economy.” The ACEEE report finds that adopting their recommended policies is attainable and would cost states less than their business-as-usual approach to meeting electricity demand, reduce pollution, and create 611,000 new jobs.

When it comes to the damages caused by flooding and severe storms, Patterson explains, pre-existing socio-political factors such as housing quality and homeownership affect how poor, elderly and minority residents are impacted by disasters. Displaced residents might be eligible for hotel reimbursements, for example, but such assistance doesn’t help those who can’t afford the upfront cost of lengthy hotel stays. “The marginalized get even further marginalized in disasters,” she says.

For Patterson, the policy details the EPA and states will grapple with during the coming years will have a tangible effect, both by reducing the amount of pollution that harms communities near power plants and by shifting the environmental and public health costs of carbon to fossil fuel companies.

“By putting in carbon pollution standards, it levels who’s paying the costs by [making it] the responsibility of energy companies instead of letting them live high off the hog while others are choking on pollution,” she says.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment