Citizens ask courts to investigate fly ash project for New River

PEARISBURG, VA – An unusual lawsuit by a citizens group asks for a grand jury investigation into a controversial coal waste project on the banks of the New River.

The Concerned Citizens of Giles County filed the lawsuit on January 8, hoping to stop the project, which would accept coal fly ash, slag and other combustion wastes from a nearby electric power plant operated by American Electric Power at Glen Lyn. The suit is based on a section of Virginia code that allows court-appointed citizens to investigate public nuisances.

“If used correctly, this could be a powerful tool to aid this (environmental) cause,” said John Robertson, the citizens’ attorney, of the petition against public nuisance process. The Giles foundation responded by saying that technically, the law only covers existing nuisances, and no fly ash has yet been placed on the site.

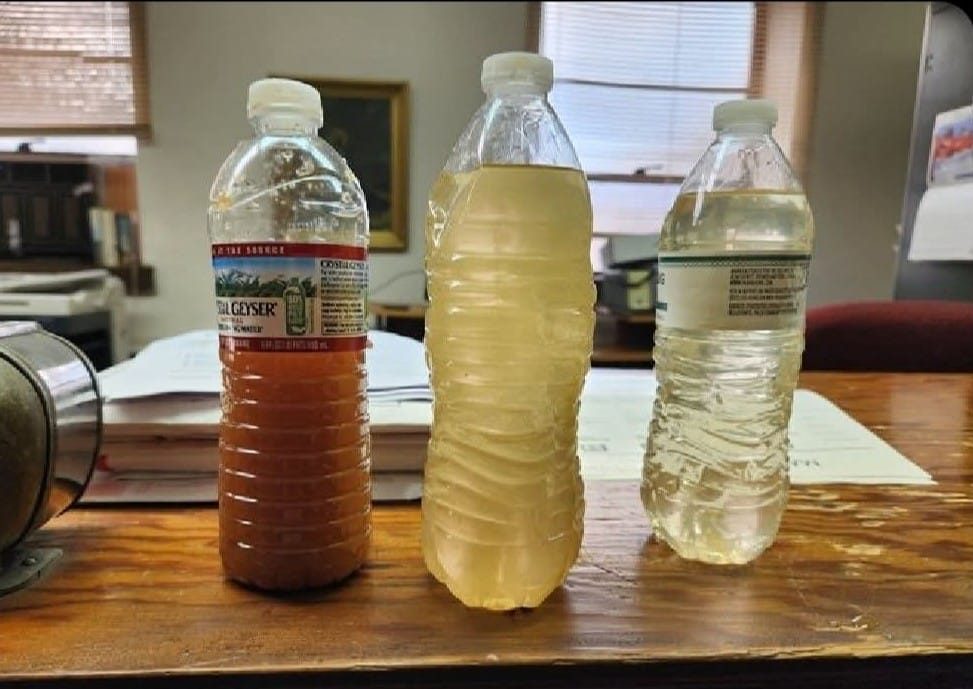

The citizens said the waste project is a threat to public health and property values because fly ash which will be placed on the site has high levels of heavy metals, arsenic and other toxic materials. In addition, the design of the project is not likely to protect against groundwater contamination, the citizens group said.

Fly ash mixed with cement is sometimes considered a “green” building material, since it is immobilized in the concrete. In contrast, the Giles fly ash would be used as loose fill, with little protection from flooding or groundwater seepage. State and federal regulations make practically no distinction between concrete and loose fill, regarding both as beneficial uses. As a result, no safeguards are in place.

“You’re just looking at a catastrophe waiting to happen,” said Britt Stoudenmire, one of the participants in the lawsuit. “Fly ash is fairly benign if it’s controlled – but when you put the stuff near groundwater, it is a much bigger issue.”

A “win-win” proposition?

The Giles fly ash project, named “Cumberland Park,” was announced to residents in August, 2007, although it had been planned by a few county officials and AEP for at least two years. Construction began in November.

The idea behind the project is to make money for the county’s educational foundation, the Giles County Partnership for Excellence Foundation (GCPEF), according to Howard Spencer, a member of the partnership’s board and also an elected county supervisor. The partnership operates independently, without oversight from the school board or other members of the board of supervisors. One of the foundation’s directors, Joe Ryder, is an employee at the Glen Lyn plant and is listed as a designated spokesman.

The project involves dumping about 300,000 tons of loosely compacted fly ash on a seven acre site on the New River flood plain near the West Virginia border. A 22 foot barrier would separate it from the river. The barrier is two feet taller than the 100 year flood level. Behind the barrier, the lowest part of the fly ash deposit would be within six feet of the water table.

The foundation would earn about $10 per ton for receiving the fly ash. The foundation’s web site says that eventually they would sell the land for commercial development, although critics find this hard to believe. If the land were to be sold, it would make even more money, creating a “win-win” proposition, according to the project web site.

The fly ash dump would “create jobs, provide a significant donation to the Giles Technology Center, and consider the environmental needs and concerns of the New River,” according to the project web site.

The plan did not need a permit from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, but DEQ official Aziz Farahmand said his agency will “still have over site of these projects although no permit is required.” He went on to say: “In this case the site is inspected by DEQ. The material was covered under Virginia solid waste management regulations before coal combustion byproduct regulations were established. Beneficial use of the material was covered under solid waste management regulations in the past.”

However, no inspections would actually be required, no groundwater monitoring would be required, and no financial assurance of long term structural stability or groundwater purity would be required.

AEP spokesman John Shepelwich said that AEP was committed to the plan and would install two monitoring wells. “We don’t feel there is a hazard to the community or the river,” Shepelwich said.

Increasing nationwide controversy

Every year, 120 million tons of fly ash form the residue of 1.1 billion tons of coal burned for electricity. Coal waste is the second largest waste stream in America after municipal solid waste. A train with cars full of a year’s fly ash production would stretch 9,600 miles.

Fly ash is often been used to make grout, asphalt, Portland cement, roofing tiles and filler for other products. In 2005, 29.1 tons of fly ash were recycled, but if all of it had been recycled, 27,500 acres of landfills would have been saved, according to the American Coal Ash Association.

Fly ash disposal has become increasingly controversial over the years. Studies from the 1980s concluded that fly ash was harmless, but more recent scientific and EPA assessments have sounded alarms.

Environmental groups have been alarmed at the groundwater contamination by heavy metals from coal fly ash. Incidents have taken place all over the country where old fly ash deposits have broken loose, contaminating neighborhoods, threatening health and reducing property values. Fish and other species die quickly when directly exposed to fly ash, and those exposed indirectly accumulate heavy metals in their bodies, harming the ecosystem and posing a serious health risk to anglers.

Undeterred, the coal and utility industries keep insisting that fly ash is harmless. Yet in 2003, EPA identified over 70 sites nationwide where fly ash and similar coal power plant waste has contaminated surface and groundwater. The next year, 130 environmental groups petitioned the federal government to stop allowing fly ash to be dumped where it could come into contact with drinking water supplies.

At the time, EPA put off a decision on new regulations for 18 months. Five years later, regulations have yet to be written, although two years ago, a National Science Foundation report urged EPA to begin regulation.

In the summer of 2007, the EPA released a national risk assessment on coal fly ash disposal. One of the most important factors involved in risk was whether runoff could carry contaminants away from the site and into groundwater.

The cancer risk from arsenic is one of the biggest issues with fly ash. People drinking groundwater contaminated by a landfill that did not use a plastic liner had a 10,000 times greater than allowable risk of cancer, the EPA said. Other risks include high levels of mercury, lead and other heavy metal contaminants.

Communities in Indiana, Pennsylvania and Maryland have already experienced severe fly ash problems. Water supplies had to be shut down in 2004 in the town of Pines, Indiana, and families were provided with bottled water after molybdenum showed up the town’s drinking water.

In September of 2007, the Boston-based Clean Air Task Force and EarthJustice released a report on the use of coal fly ash to fill in Pennsylvania mines. In 10 of 15 mines examined across the state, groundwater and streams near areas where coal ash, or coal combustion waste had high levels of arsenic, lead, cadmium and selenium and other pollutants above safe standards.

In November 2007, some 34 residents of Gambrills, Maryland, filed a class action lawsuit against a power company, saying that their water was contaminated by a fly ash disposal site. The suit was filed because the claimants felt that a previous $1 million fine, levied against a utility by the state environmental agency, was inadequate.

Giles Concerned Citizens fight

After the Giles fly ash project became public last summer, a group of citizens began meeting to make plans to fight it.

An early ally was the Virginia Tech chapter of the American fisheries society, which said that the plan poses an “unacceptable risk to the fishery of the New River.” Fisheries biologist Than Hitt, writing on behalf of the society, also said he worried that there were “no plans for a temporary cover or cap on the fill site during the three years that (fly ash) will be disposed of” at the site.

“The plans for the project seem to assume that there will be no rain, snow or other major weather events like hurricanes, tropical storms or nor’easters for the three year disposal period. This is a recipe for potentially major leachate problems.” Hitt also said that due to poor quality of the leachate data provided by Appalachian Electric Power, “there is inadequate analysis of the true potential for contamination.”

Along with holding public information meetings, the citizens began showing up at board of supervisors meetings and demanded answers to questions. Most board members had not been informed of the project, and several were alarmed at being told that they had no power to stop it.

“I went to them and I said I want to try to get this developed because I want to put jobs in Giles County,” Spencer said in an exchange last October recorded by Star City Studios of Roanoke. “That’s not the concern,” responded one angry resident. “Dumping toxic waste on that site on the river is the issue.”

Spencer added that fly ash ponds downstream from Cumberland project, at AEP’s Glen Lyn plant, had been contaminating the New River for years. “For 44 years there at Glen Lyn, I go across the bridge and I look down and there’s an open fly ash – two pits side by side.”

County residents at the meeting shouted “Shame, shame” in response, and when Spencer volunteered that if they didn’t like it, they could vote him out of office, there was applause and shouts of “we’d love to.”

Spencer has also said that he does not stand to profit from foundation work. However, in 2006, Spencer was paid more than $28,000 by the foundation, according to the organization’s IRS 990 form. The 2007 form has not yet been filed, although a Freedom of Information Request for that and other tax, income and expenditure information has been made by the Concerned Citizens of Giles County.

“I think instead of serving the people, it is serving the special interest groups,” said Concerned Citizens for Giles County chair James McGrath. “There’s going to be a few people who are going to line their pockets at the expense of the health of the county and the future of tourism and recreational jobs.”

“I feel very strongly that while young men and women from this county and this nation are serving in Iraq and Afghanistan to bring democracy to the Middle East, democracy has not been served in Giles County” McGrath said.

The controversy has split the community, as old friends take opposing sides in the increasingly bitter debate. School teachers said they have been told not to allow discussion about the controversy in classes since some of the students might be sensitive about their parent’s roles in the controversy.

“This dump is located in the flood plain, and it has no liner,” said Lawanda Robertson. “This is very dangerous because of the leachate. When it rains it has nowhere else to go but down and out.”

“We’re not so green that we don’t realize we don’t have (to dispose of) fly ash,” said Stoudenmire, “but why put it on the flood plain of a river? “

More information:

Concerned Citizens of Giles County — http://www.concernedgilescitizens.org/

Concerned Citizens video — www.starcitystudios.net

Giles County Partnership for Excellence — http://gilespartnership.org)

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment