Toxic Ponds: Coal Ash Ponds Pollute North Carolina Water

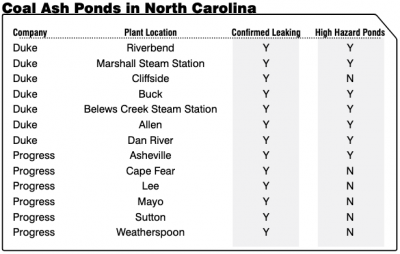

This chart shows the plant locations which were included in a data analysis conducted by

Watauga Riverkeeper Donna Lisenby. The data was originally collected by Duke and Progress

Energy. Lisenby’s analysis confirmed that all of the tested coal ash ponds were found to be

leaking toxic pollutants into the ground water. The information in the fourth column is based

on EPA’s list of high hazard coal ash ponds as of August 2009.

Thirteen coal ash ponds in North Carolina are contaminating ground water with toxic pollutants known to cause cancer and organ damage, a recent report shows.

Appalachian Voices’ Upper Watauga Riverkeeper team conducted an analysis of groundwater contamination data and reviewed the test results of wells surrounding 13 coal ash ponds located adjacent to the North Carolina’s coal-fired power plants. All of the coal ash ponds studied have been leaking toxic pollutants into groundwater—some for years.

Of the 13 coal ash ponds, seven are on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s list of high hazard ash ponds in the United States, which was released in August 2009. According to the EPA, “A high hazard potential rating indicates that a failure will probably cause loss of human life.”

After reviewing the data, Upper Watauga Riverkeeper Donna Lisenby concluded that all of the tested coal ash ponds were found to be leaking toxic heavy metals and other pollutants into nearby groundwater. The pollutants included arsenic, boron, cadmium, chloride, chromium, iron, lead, manganese, pH and sulfate. In all, the analysis found 681 instances where levels of pollutants were in excess, ranging from 1.1 to 380 times higher than North Carolina’s groundwater standard.

“The results of this data are very alarming, and we now know that some of these ponds have been leaking into the groundwater for years,” said Lisenby. “We intend to call for further oversight and clean up of coal ash pond waste to prevent additional heavy metals and other toxins from being released into our groundwater and rivers.”

In North Carolina, utilities generate millions of pounds of toxic coal ash waste annually as a byproduct of coal combustion. After coal is burned in a power plant, the leftover ash is stored in large retaining ponds, ranging in size from 26 to 512 acres.

According to Earth Justice, a nonprofit environmental law firm, “enough coal combustion waste (CCW) is generated each year in the United States to fill a train stretching from Washington, D.C. to Melbourne, Australia.”

The power plants, which are typically located on rivers, routinely discharge water from the coal ash ponds directly into the waterways. Three of the analyzed waste ponds border the Catawba River Basin, a watershed that provides drinking water to nearly 1 million residents in the Charlotte region.

A 2007 EPA Risk Assessment concluded that residents with wells who live in close proximity to coal ash ponds have as much as a 1 in 50 chance of getting cancer from drinking water contaminated by toxins such as arsenic, one of the most common and dangerous pollutants in coal ash.

The assessment also states that living near ash ponds increases the risk of damage to the liver, kidneys, lungs and other organs as a result of being exposed to toxic metals like cadmium and lead. Wildlife and ecosystems are also threatened by coal ash contaminants like boron, which at North Carolina ash ponds can be found at levels ranging from 1.4 to 16 times the safe threshold.

North Carolina’s two power utilities, Duke and Progress, submitted the original test results to the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources (NCDENR). The tests were conducted as part of a voluntary program in an agreement with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for utilities companies to self-monitor coal waste ash ponds.

Because testing has been voluntary and the frequency and distribution of sampling was determined by the power companies and not by federal or state regulation, NCDENR is still trying to confirm the results before they determine whether corrective action can be required under current state law.

“Because coal ash is minimally regulated in North Carolina, the exact impacts to downstream communities are unknown, and further testing is needed,” said Lisenby.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment