Potential Federal Action Would Address Common and Harmful “Forever Chemicals”

UPDATE: On October 18, EPA announced a plan outlining how the agency aims to tackle PFAS chemicals between 2021 and 2024. The plan received a mixed reaction from environmental groups, with some applauding the action and others urging Congress to pass laws that set clear deadlines for the agency to regulate PFAS. Read more related to the Oct. 18 announcement at NC Policy Watch.

By Hannah Wilson-Black

Congress and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency may soon take serious regulatory action against a common but little-known family of man-made chemicals that has been sickening communities across the U.S for decades.

In September, the EPA announced its intention to set its first standards for PFAS concentrations in industrial wastewater discharges. And in October, the federal agency agreed to respond within 90 days to a petition from North Carolina health and environmental justice groups asking that Chemours, a chemical company with a history of discharging PFAS into the Cape Fear River watershed, be required to test for impacts to human and environmental health.

Separately, in July the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would require the EPA to broadly regulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. The Senate has not yet held a committee vote. Two representatives are also looking to include funding for fire departments to replace PFAS-laden supplies into the ongoing budget reconciliation process. If these changes become law, they could provide a sense of justice to those harmed by toxic PFAS exposure and prevent further persistence of PFAS in water and air.

The PFAS Action Act, which passed the House 241-183, would require the EPA to establish drinking water limits for two common PFAS known as PFOA and PFOS — perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, respectively. The agency would also be given five years to determine how many more varieties of PFAS need to be regulated. The chemical family would be classified as a “hazardous substance” under the Superfund program and PFOA and PFOS would be classified as “hazardous air pollutants” under the Clean Air Act. EPA would also be required to determine whether PFAS should be regulated under the Clean Water Act. If so, a limit would be set on the amount of PFAS that industrial sites can discharge.

Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.), who sponsored the PFAS Action Act, speaks during the U.S. House floor debate on July 21, 2021. Photo courtesy U.S. House

“The Most Persistent Chemicals Ever Made”

PFAS, also dubbed “forever chemicals,” are not currently regulated by the EPA, despite the danger they pose. A 2011 study using 10 years of blood serum data from a representative sample of United States residents found PFAS in the blood of more than 95% of participants. Research into the health impacts of PFAS is ongoing, but studies have found a “probable link” to ulcerative colitis and two varieties of cancer, among other conditions. Additional studies referenced by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that the odorless, tasteless chemicals may raise cholesterol and cause changes in liver enzymes, among other health issues.

“It’s just kind of mind-blowing how many systems of the body are impacted [by PFAS],” says Sierra Club Senior Toxics Advisor Sonya Lunder, the lead author of a February public comment letter to the EPA calling for PFAS regulations that was signed by 30 environmental groups.

The same carbon-fluorine bond that makes PFAS ideal for use in heat-, water- and oil-resistant products like non-stick Teflon pans, firefighting foam and food packaging also means PFAS “may be the most persistent chemicals ever made,” according to the letter. The manufacture of PFOA and PFOS has been voluntarily phased out by the chemical industry, but the two chemicals persist in soil, air, groundwater and surface water.

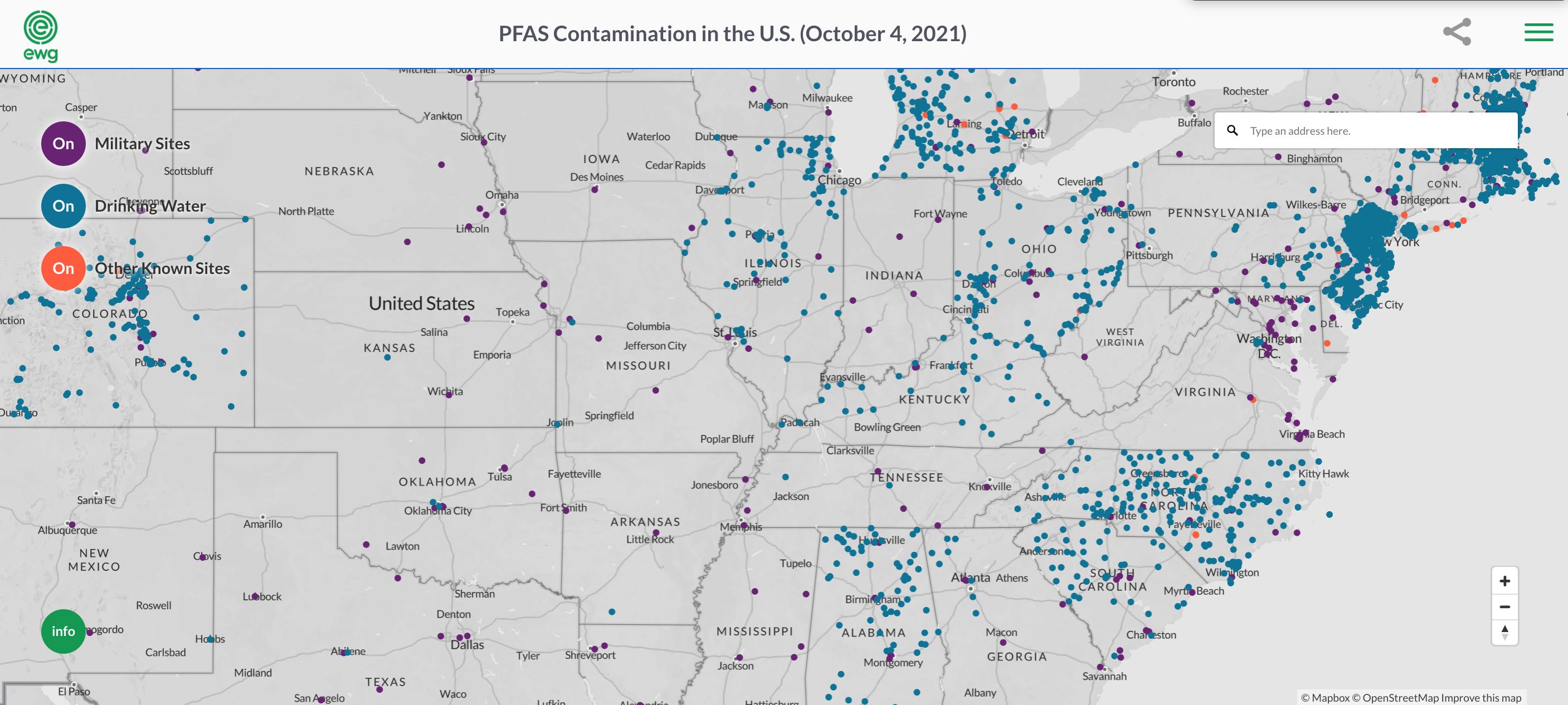

The Environmental Working Group, a national public and environmental health organization, hosts an interactive map of known PFAS contamination in the U.S. This screenshot shows a version of the map updated Oct. 4, 2021. Explore the interactive map and click on each dot to learn more about the site by visiting the interactive map here. Copyright © Environmental Working Group, www.ewg.org. Reproduced with permission.

Additionally, there are indications that industry replacements for PFOA and PFOS, alternative chemicals known as “short-chain” PFAS, are themselves dangerous. GenX, a short-chain chemical still in use as a replacement for PFOA, has caused cancerous tumors in rats at high doses and is being studied closely by the EPA.

The chemical industry “is shifting from one, well-studied chemical to another, slightly different one,” says Lunder. “And the fact that it takes scientists and regulators decades to figure out what it is, study it, figure out if it’s a problem, and regulate it.”

The EPA has been monitoring and encouraging industries to phase out PFAS for years, though the chemicals have never been federally regulated in the U.S. The PFAS Action Act would require significant regulation and set a stricter timeline to speed up development of a drinking water standard, a process that, according to Lunder, normally takes eight or 10 years if it happens at all.

Blood Levels of the Most Common PFAS in People in the United States from 2000-2014

Four common types of PFAS were consistently found in Americans’ blood throughout the early 21st century. Chart by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

A Job for State or Federal Government?

A common argument from opponents of the bill is that the legislation is a federal overstep. In a statement to the Charleston Gazette-Mail, U.S. Rep. Carol Miller (R-W.Va.) said, “It’s crucial we protect public health and the environment — especially in the Mountain State — from the challenges associated with PFAS, but House Democrats’ overreaching legislation is not the answer.”

In the eyes of some state politicians and advocates, however, strong federal intervention is just what is needed for PFAS.

A letter in favor of the PFAS Action Act signed by five governors in the Great Lakes region reads, “A strong federal law is needed to ensure a consistent national framework for addressing PFAS and because not all states have the capacity or legal frameworks in place to undertake state-driven actions.”

“I think state agencies are sometimes designed to fail, politically, or that they’ve been manipulated politically too much to be successful, which is unfortunate,” says Emily Donovan, co-founder of Fayetteville, North Carolina, volunteer organization Clean Cape Fear. Donovan and fellow Fayetteville residents founded the organization in 2017 after a local newspaper reported that DuPont Chemical Company had been releasing PFAS into the source of their drinking water, the Cape Fear River.

“I just assumed that when I turned on my tap it was safe,” Donovan says. “And what I realized was it was clear — it wasn’t clean.”

Most municipal water authorities do not possess the technology to screen PFAS out of their water, because it is not regulated as a hazardous chemical by federal law. Just seven states have enforceable limits on the amount of PFAS in drinking water, and 10 states have guidelines or issue notices for high PFAS levels, according to the environmental health network Safer States.

According to Donovan, states with particularly high concentrations of PFAS often lack state-level PFAS regulation. North Carolina, which does not have enforceable limits on PFAS levels in water, is an example. DuPont and, later, DuPont spinoff company Chemours, dumped waste that contained PFAS into the Cape Fear River from 1980 to 2017, according to Clean Cape Fear.

The Cape Fear River begins in the central part of the state and flows southeast. Photo by Blipperman, license throughWikimedia Commons

Eric Engle of West Virginia organization Mid-Ohio Valley Climate Action is dealing with similar PFAS contamination issues in his state, especially in the city of Parkersburg, and sees federal regulation as the answer.

“We’re going to need to look towards federal legislation and regulatory action more than any other vehicle for overcoming [PFAS pollution],” says Engle. “Especially at the state level in West Virginia, I don’t expect much from our legislature or governor at all.”

Parkersburg, W.Va. v.s. DuPont

Parkersburg, West Virginia, is a powerful example of the effects of PFAS. The city has made headlines periodically since Parkersburg farmer Wilbur Tennant and attorney Rob Bilott first sued DuPont Chemical in 1998 after Tennant’s cows began mysteriously dying.

DuPont began manufacturing the chemical PFOA, also known as “C8,” at its Parkersburg plant in 1951, in order to make Teflon products. In 2001, Bilott brought a class action lawsuit against the chemical company on behalf of 80,000 plaintiffs in six Ohio River water districts whose drinking water was contaminated by PFOA. In 2011 and 2012, a scientific panel finished a series of studies in the Parkersburg area and issued reports concluding that PFOA did indeed have a “probable link” to ulcerative colitis, pregnancy-induced hypertension, thyroid disease, testicular cancer and kidney cancer.

Yet another Bilott lawsuit is ongoing — the lawyer filed a class-action lawsuit in 2018 on behalf of all Americans with PFAS in their blood.

“The case of this one farmer in the Parkersburg area really was the shot over the bow that started all of this,” says Engle.

“[Parkersburg residents] were the people who taught us … the intense toxicity of PFAS,” says Sierra Club’s Sonya Lunder. Even with the settlements, she added, “justice for the people who had those intense exposures is lacking.”

Who Pays and How?

Litigation like Bilott’s lawsuits is important to advocates because it can force the companies responsible for PFAS-related harm to pay damages to individuals or pay for special technology to filter PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Bills like the PFAS Action Act would allow Superfund law to hold companies such as DuPont, Chemours and 3M accountable for PFAS cleanup costs, but would not necessarily force them to cover additional costs. As a result, communities often aim to receive damage payments and water filtration funding through lawsuits, Lunder explains.

A group of 13 organizations representing the nation’s municipal governments and drinking water and wastewater facilities submitted a July letter to Congress stating their apprehension that water municipalities and their ratepayers could be held accountable for cleaning up PFAS pollution they did not create. The organizations expressed concern that public water treatment plants will have to pay for PFAS cleanup both through purchasing new equipment to meet potential drinking water standards and through Superfund site rules that might designate PFAS disposal sites as polluted areas that municipalities must clean up.

“Wastewater utilities would face … liability through no fault of their own because they receive PFAS chemicals through the raw influent that arrives at the treatment plant,” the letter states. The groups state that water and wastewater utilities should be excluded from certain requirements of Superfund law through a special exemption.

“I think cost of pollution cleanup is a really important issue,” Lunder says, “but I think if we’re thinking about this big picture, the public is paying the price. Either you pay incredibly high water bills or you’re subjected to lifelong exposure to highly toxic chemicals. This is another place where the system is broken.”

The Future of PFAS

The PFAS Action Act passed the House and remains in the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, which may recommend the bill for a Senate vote if the issue appears to have enough bipartisan support. Apart from the bill, Reps. James McGovern (D-Mass.) and Daniel Kildee (D-Mich.) are urging the House to include funding for the removal and replacement of firefighting foam that contains PFAS in the budget reconciliation process currently underway for fiscal year 2022.

“In the meantime,” Lunder says, “[Dupont, Chemours and 3M] continue to make, use, and skirt responsibility for the lifetime and generation impacts of these chemicals on people and the environment.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment