Grazing In The Sun: Enterprising Farmers Pair Agriculture With Solar Power

Before a solar developer came to town, Cody Moore was a heavy equipment diesel mechanic and hobby cattle farmer in Washington County, Tennessee.

He enjoyed his job but had always hoped that if he could scratch out a living in full-time agriculture work, he would make a go of it.

Today, the 27-year-old husband and father of two is a full-time farmer grazing sheep on more than 400 acres of land across five solar sites owned by Silicon Ranch Corporation, a solar developer that operates 25 similar projects across five different states. Moore expects his flock of close to 300 ewes to double in size by next year.

“I never thought that I would be grazing sheep at a solar site,” Moore says. “If it weren’t for these solar farms, there would be no way I could do this. It would not pencil in for me to have been able to quit my job and be able to farm. There’s just no other way.”

Moore is involved in agrivoltaics, which is the practice of using land for both agricultural and solar energy production. Unlike single-use solar fields, agrivoltaics involves traditional ground-mounted solar arrays where panels are elevated or spaced out to allow for crop production, pollinator habitats or grazing. It also includes solar technology installed on or around greenhouses.

Agrivoltaics’ dual-use approach allows both industries to coexist on the same parcel of land and is rising in popularity. The industry’s most comprehensive study comes from the InSPIRE project at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. According to the InSPIRE agrivoltaics map at the time of publication, 598 sites across the United States represent 10.3 gigawatts and 64,688 acres — figures that have nearly doubled since 2020. That means solar sites on current working farmland are creating enough power for more than a million U.S. households.

Most solar development isn’t happening in Appalachia — California, Texas, Florida and other sunnier states are still leading the charge, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. However, agrivoltaics advocates in the region believe that when done well, the co-location of renewable energy and agriculture can offer numerous environmental and economic benefits for Appalachian communities.

Solar grazing: Empowering farmers, one flock at a time

Many agrivoltaic projects in the U.S. involve sheep grazing, where shepherds like Moore — either contracted by solar developers or hired internally — use their flock to control vegetation.

“It’s no different than you would hire someone to mow your yard,” says Eric Bronson, owner of James River Grazing Company. “I just happen to do some of it with sheep.”

Bronson grazes sheep on a nearly 2,000-acre, 175-megawatt site in Charles City, Virginia. He is also the Mid-Atlantic senior Smart Solar specialist for American Farmland Trust, a nonprofit with the goals of protecting farmland and farmers and promoting environmentally sound farming practices in Appalachia and the rest of the country.

He grew up in Virginia and returned to the region after college, where he managed a small cattle operation but had difficulty accessing land. Like many farmers, Bronson also worked an off-farm job for nearly a decade before a solar facility opened up near him and he jumped at the chance to get into agrivoltaics. Like Moore, he says he would be unable to farm full-time without solar.

“I think Appalachia is in the perfect position when we look at agrivoltaics,” Bronson says. “One thing that’s unique about the Appalachian region is when we look at Southwest Virginia, where the bulk of sheep production happens in the state. It has the highest density and number of sheep and producers. That’s where we would like to see people be able to harness these opportunities.”

Gray’s LAMBscaping, owned and operated by Jess and Marcus Gray in Chatham, Virginia, manages thousands of acres of agrivoltaic projects across the state, working with major organizations and utility companies, including Dominion Energy. In 2025, the company is set to graze around 4,000 acres across Virginia.

“We’re practicing this idea of making [land] better than before we got there,” says Jess Gray, who serves as the company’s CEO. “When it gets returned to farmland, it’s going to be thriving farmland. We’re putting in more than we’re taking out. And I wish more people would recognize that dual-use solar is a fantastic idea because we’re getting clean energy but also taking time and almost letting the field be fallow again.”

Over time, sheep improve the soil they graze on through natural fertilization, depositing rich nutrients back into the soil, explains Jess Gray.

“We are changing the soil in a good way and a super positive way,” she says. “We’re giving back what it needs.”

Sheep grazing opportunities can also take “some of the volatility out of the agricultural market,” says Moore. Farmers can count on a steady income stream from solar companies for vegetation management and then sell their sheep. It also gives farmers the chance to diversify into new income streams.

“It’s about getting people to understand that agriculture changes, and it’s supposed to change,” Jess Gray says. “It doesn’t have to look the way it did when your grandparents started farming.”

However, not every farmer is as keen as Moore, Bronson or Gray when presented with the opportunity to enter the solar grazing space. Around a decade ago, Johnny Rogers, owner of Rogers Cattle Company, was leasing his pasture-based livestock farm in North Carolina when his landlord decided to build a 30-acre solar array on the property.

Though he now refers to this situation as “destiny,” he was initially uneasy and “miserable to live with” for a few weeks until his landlord encouraged him to talk to the solar developer about sheep grazing.

“All I could see was this is the end of this chapter,” Rogers says. “We’re gonna cover this whole place with solar panels. And to make it even more interesting and stressful, we live in a house on that same farm. So, we were going to lose our house, our principal place of doing business — all because of this solar farm.”

Instead, Rogers turned the solar installation into a way to meet his biggest expense — feed cost. The solar company compensates him for grazing and mowing, also known as total vegetation management.

“Originally, what I thought was going to be a bad situation actually turned out to be a significant part of our farming enterprise from a revenue standpoint,” says Rogers, who now also serves as the program coordinator for North Carolina State University Extension’s Amazing Grazing Program and sits on the advisory board of the American Solar Grazing Association. “The sheep are getting paid to graze that grass.”

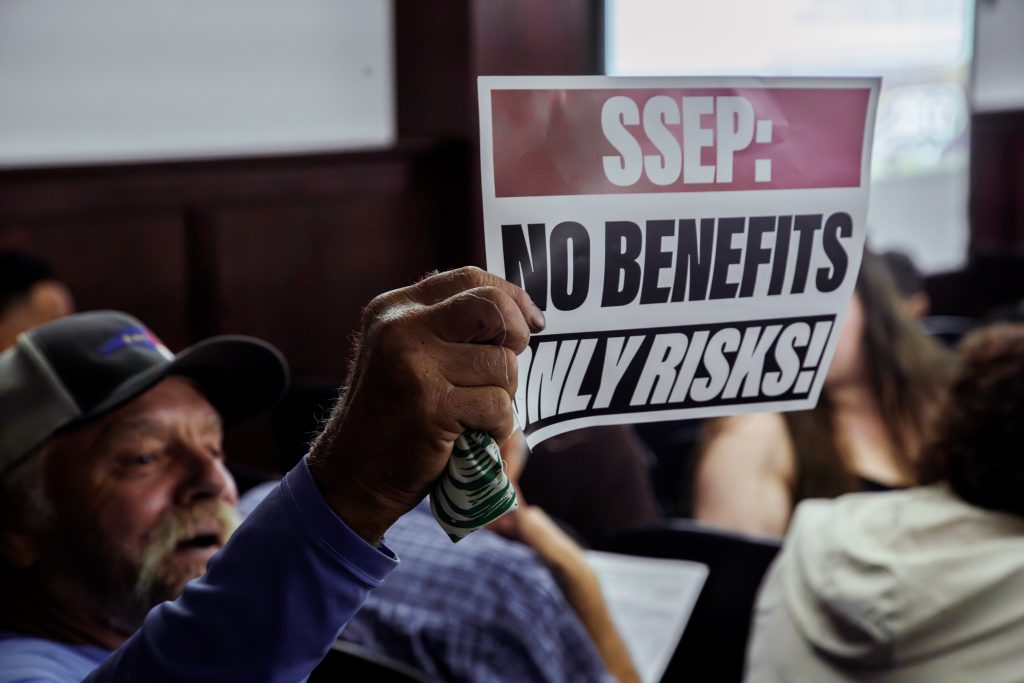

Land use concerns and misinformation

As renewable energy demand has increased in recent years, the large-scale deployment of solar energy presents concerns about land use and sustainable land management practices, particularly on high-quality agricultural land.

Ashish Kapoor, senior energy and climate advisor at Piedmont Environmental Council, a Virginia conservation nonprofit, cautions that the tension between prime agricultural lands and the renewable energy transition “runs pretty deep” and emphasizes the need for farmer-first approaches.

“Dual use is two things together,” Kapoor says. “Thoughtfully developing projects from the agricultural side will be critical at the small and large scale for agrivoltaics to be something that’s viable and is accepted.”

Bronson acknowledges that anyone in agriculture is aware of that tension point around land use. At the American Farmland Trust, he and others on his team serve as a middle ground between solar and agriculture to facilitate “smart solar” solutions and help equip farmers with the tools they need to be successful in the space.

“We have to evaluate each project on its own merits because solar is not this giant monolithic thing that’s spreading across the landscape,” Bronson says. “I think it’s really important that the public knows that continued agricultural production on [land with solar arrays] is possible. And we can signal to our elected officials that this is important to us.”

Additionally, Jess Gray has been surprised to encounter a lot of misinformation and anti-solar sentiment in the field, including those who believe no farmers should be building or participating in solar.

“What frustrates me is nobody ever took the time to talk to the farmer,” Gray says. “Some families have been slugging away for generations, and they’re in debt to their eyeballs. Solar provides an opportunity to potentially provide for their family or lift generational debt. It’s hard not to weigh that out.”

Gray works hard to showcase the opportunities that come with agrivoltaics and the importance of uplifting rural voices and inviting them into the space.

“It’s a really welcoming, open industry,” says Jess. “Let’s build those local economies that we’ve neglected and moved without them. Let’s give them tools [so] they can be successful.”

By Moore’s estimate, skyrocketing property values in his region have made the odds of a farmer purchasing land and keeping it in agricultural production “slim to none.”

“It’s important for people to realize that although a family farm might be being sold and a solar company might be purchasing it, it gives young people like me the opportunity to participate in agriculture,” Moore says. “This gives me the opportunity to feed my family doing what I love.”

“I can’t farm a subdivision,” Moore jokes.

Future opportunities with agrivoltaics

Beyond sheep grazing, there are plenty more agrivoltaic applications and opportunities for farmers, developers and landowners alike.

In the Southeast, Loran Shallenberger, senior director of regenerative energy operations at Silicon Ranch Corporation, says, “Cattle is still king.” Even so, co-locating cattle grazing with solar has not taken off quite as quickly as sheep grazing because solar arrays must be raised off the ground higher to avoid animal damage, which leads to increased construction and maintenance costs.

Silicon Ranch Corporation launched the CattleTracker project, funded by the Department of Energy, to create a beneficial solution for all parties — developers, farmers and cows. CattleTracker is the solar company’s unique system and approach to grazing cattle on and around solar.

“By the end of the summer, we’ll have an operational, utility-scale CattleTracker, where we will work out the kinks of grazing cattle [with solar],” Shallenberger says. “There is a modest cost increase on the construction side because there’s more steel. But ultimately, we think we’ll see enough savings on the land management side to compensate for that additional expenditure.”

Meanwhile, Allison Wickham, founder of Siller Pollinator Company, receives nearly half of her company’s revenue from pollinator services for solar installations. The Charlottesville-based company also offers beekeeping classes and sells beekeeping equipment.

Many states, like Virginia, where Wickham primarily operates, have dedicated programs or incentives to encourage pollinator-friendly solar projects. Developers hire experts like Wickham to remove invasive species and install native plants on portions of project land not covered by solar arrays to control vegetation and support endangered pollinators, including moths, butterflies and honeybees.

“I will boldly say that solar is probably the best opportunity for native pollinators that we have seen in a very long time,” Wickham says. “It’s this amazing, nonpartisan environmental effort to increase the percentage of native flowers that we have out there, which is just good for everybody. It’s good for the land, the site, the bugs, the birds and the people.”

Wickham also oversees one solar site that installed honeybee hives, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as domesticated livestock. Wickham says the practice faces a harder uphill climb than sheep grazing due to misunderstandings about the level of risk for solar workers near hives and how to implement this form of agrivoltaics.

Despite this slow start, she is hopeful of some rising interest from the solar industry, including Dominion Energy’s recent partnership with Mountain House Apiaries to install honeybee hives on its 1.6 megawatt Black Bear Solar project in Buckingham County, Virginia.

“It will present opportunities for beekeepers, produce food on-site and improve the local ecosystem,” Wickham says. “It’s a win-win-win.”

Another project in Northern Virginia is exploring the possible benefits of agrivoltaics. Piedmont Environmental Council is installing 42 solar panels at its Community Farm at Roundabout Meadows in Loudoun County to explore the feasibility of crop-based agrivoltaics and inform future policy and projects. The panels will be spaced out and raised 6 feet to allow for both raised bed and in-ground crop growth underneath.

Led by the council’s Kapoor, the project should be completed later this year and serve as a demonstration site that local farmers, nonprofit organizations, developers and policymakers can visit and see how communities can retain rural character, continue agricultural activity and provide clean energy — all at once.

“We want to share very clearly and openly and in ways that are not intimidating for folks that are thinking about these projects themselves,” Kapoor says. “People can start thinking about, at least in our region, that juxtaposition of agriculture and solar in a different way, and that can then inform agrivoltaics, small and large, in a productive way in the next five years.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “Grazing In The Sun: Enterprising Farmers Pair Agriculture With Solar Power”

-

This is one of the few real win-win setups in clean energy today. Solar grazing gives farmers land access without the huge upfront costs and opens steady income from managing vegetation. I’ve talked to landowners in Ontario facing similar issues—priced out of expansion, limited options. Agrivoltaics can offer a bridge back to agriculture for younger farmers, which we badly need.

That said, it’s not all smooth. Not every site fits sheep grazing. Terrain, local opposition, unclear rules, and anti-solar noise can kill momentum before a project starts. And some developers still treat agriculture like an afterthought. That needs to change if this is going to scale right.

Still, there’s real potential here. We’re talking about thousands of underused acres producing food and power without displacing one or the other. That’s rare. We need more of these farmer-first approaches that actually work on the ground.

Leave a Comment