New Draft Safety Standard for Exposure to Silica Dust

“The dust you see usually doesn’t hurt you very bad,” Jerry Coleman, a retired coal miner with black lung disease living in Kanawha County, West Virginia, told Willie Dodson for an April article in the Appalachian Voice. “It’s the dust you don’t see that gets you. The bigger dust gets in your mouth and your nose and you can spit it out. But it’s the small dust — the silica — that you don’t pay attention to. Over time, you’re used to doing certain things, and you get to noticing that you can’t do them anymore [because of black lung].” Above, Coleman speaks at a May 2022 press conference. Photo by Willie Dodson

By Molly Moore

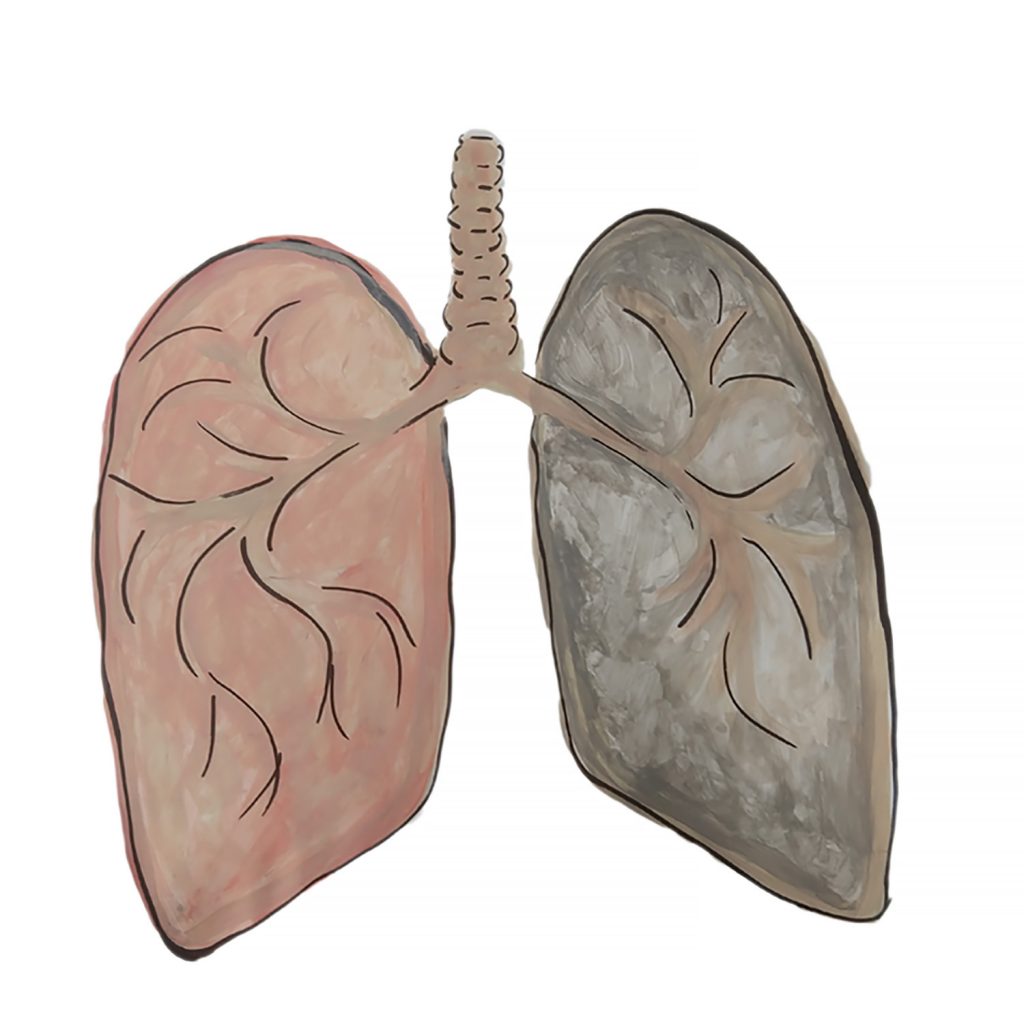

The rock layers surrounding coal seams are deadly for miners. The silica dust they produce is even more hazardous to human lungs than the coal dust typically associated with black lung disease. Coal miners, who are often exposed to both, know the toll too well.

In Central Appalachia, one in five tenured miners now has black lung disease, and one in 20 has the most severe and utterly disabling form of black lung. These fatal diseases are preventable, yet in recent years they have become more common and are hitting younger workers — some who have spent just a handful of years as miners.

Silica is also a carcinogen that causes other respiratory and kidney ailments. That’s why the Mine Safety and Health Administration proposed new regulations June 30 to reduce worker exposure to silica dust. The draft silica rule cuts the amount of silica dust a miner can be exposed to during an eight-hour shift by half, from 100 micrograms per cubic meter to 50, granting miners the same silica exposure limit as workers in all other industries.

Miners and their supporters were glad to see the draft rule’s release.

“We need the strongest possible silica standard to give miners a better quality of life, and longer lives to live,” said Vonda Robinson, vice president of the National Black Lung Association.

Under the proposed rule, if miners are exposed to more than 50 micrograms per cubic meter of silica dust, the mine operator would have to immediately correct the problem and perform sampling to monitor silica levels. The rule also sets an “action level” or exposure threshold of 25 micrograms per cubic meter. If miners reach that exposure threshold, the mine operator must conduct periodic sampling until the level drops below the limit.

“Miners will tell you that company-submitted samples can be fudged fairly easily to appear compliant regardless of actual conditions in the workplace, and that one-off samples collected by MSHA inspectors can be inadequate as well, since a mine operator can change how a mine is run for one day without seriously addressing ongoing issues,” said Willie Dodson, Central Appalachian field coordinator with Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper. “Ideally, MSHA inspectors would take samples day after day after day in a given mine to determine compliance. As miners and advocates continue to engage MSHA on this matter, we’ll be pushing to ensure strong sampling methodologies are in place.”

Instead of relying primarily on silica monitoring that is conducted by coal companies, as the draft rule does, miner advocates would like to see MSHA inspectors themselves routinely collect silica dust samples over full shifts and multiple days, without providing advance notice to the mine operators. Advocates also want to see silica sampling required at every aspect of the mining process where miners might be exposed to high dust levels, and want the rule to set monetary fines for companies that violate the standards that are high enough to compel compliance.

Another concern flagged by Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center and other advocates is that the draft rule does not require mines to shut down if the silica dust level is dangerously high. Instead, it allows coal companies to rely on respirators worn by miners for an unspecified amount of time, even though it’s known that mine conditions make it extremely challenging for workers to wear heavy-duty respirators.

The draft silica dust rule is enforced separately from coal dust standards, and also applies to other types of mines. It requires medical surveillance programs at non-coal mines, expanding a program already in use at coal mines to gain a better understanding of how silica exposure is affecting workers at mines for sand and gravel, stone, metal and more.

While miners and advocates were glad to see a draft rule released, they also expressed disappointment that the safety standards weren’t updated sooner.

“It should’ve been done a long time ago,” Robinson said.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health first recommended a 50 microgram per cubic meter exposure limit for silica dust in 1974, a recommendation it reiterated several times over the following decades. In 2008, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, a nonprofit research organization, set its recommended silica exposure level at 25 micrograms per cubic meter. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration adopted the 50 microgram per cubic meter standard for non-mining industries in 2016.

Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center,a nonprofit organization that advocates for coal policy changes and provides free legal services for miners with black lung and their families, petitioned MSHA to set a silica limit in 2010 and again in 2021.

MSHA released its draft rule for interagency review in January. In the weeks before the rule was announced, six Appalachian senators sent a letter calling on the Office of Management And Budget to speed the rule’s release, followed by a similar letter from 28 organizations, including the United Mine Workers of America.

“This is the first step of many that will be required,” said UMWA International President Cecil Roberts in a statement commending the rule. “We must get this rule finalized as soon as possible. And then, we must ensure that mine operators follow the rule, the government enforces it and penalizes those who violate it. We must remain vigilant until the day comes when no miner contracts this disease and we can finally say we have wiped out black lung for good.”

Ways to Get Involved

Learn about upcoming public hearings and webinars. Share your thoughts with MSHA regulators by submitting a comment.

The rule’s success in protecting miner health will hinge in large part on how well MSHA can enforce the standard.

As of 2023, there are nearly 50% fewer coal mine inspectors than there were in 2013, according to a review of federal budget archives. Congress has not allocated enough money to the agency to keep up with inflation and maintain staffing levels.

In March, the Biden administration proposed a 13% budget increase for MSHA for fiscal year 2024, but in June, Congress enacted the Fiscal Responsibility Act to avoid default on the nation’s debt. The law caps fiscal year 2024 government agency spending at fiscal year 2023 levels. While the budget for the agency and its inspectors is still under negotiation, Congress is highly unlikely to increase it.

The silica rule is open for public comment through August 28.

This article was updated on Aug. 3 from the version published in print on July 20 to reflect analysis of the rule from mine safety advocates.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *