Researchers Discuss How Climate Change Impacts Health in Rural Mountain Communities

By Cameron Stuart

Appalachian State faculty member Christine Hendren discusses the work of Appalachian State University’s Research Institute for Environment, Energy and Economics to begin the event, joined by fellow App State colleagues Maggie Sugg and Gary McCullough. Photo courtesy of Maggie Sugg

Unless the current greenhouse gas emission rate is lowered, North Carolina is expected to warm up to 10 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century.

This finding was one of many discussed at the Climate Change and Health in Rural Mountain Environments collaborative workshop April 8 at Appalachian State University.

The workshop was designed to “identify research needs and priorities for our region at the intersection of climate and health for rural mountain environments,” according to the university’s website.

The event began with four speakers discussing specific climate change impacts in rural mountain communities: heat-related illness, vector borne diseases, mental health and maternal health and national scientific assessments.

Faculty and researchers split into breakout groups to discuss emerging issues in western North Carolina and the Appalachian region. They plan to compile their data and findings in a journal article submission to identify necessary research and funding options.

Topics discussed include environmental changes, reaching vulnerable populations, healthcare access during weather disasters, mental health support, vector-borne disease, food security and public education on climate change.

Environmental Impacts: Warming and Flooding

North Carolina has warmed by 1 degree Fahrenheit since 1901, while the planet overall has warmed by 2 degrees, according to speaker Kathie Dello, state climatologist and director of the North Carolina State Climate Office. However, this warming has not come from increasing daytime temperatures.

“If we’re worried about rural health and we’re worried about exposure to heat, we’re certainly going to think about those really hot North Carolina days,” Dello said. But, she added, “Our warming trend, that 1 degree Fahrenheit those past few decades, are really dominated by the nighttime temperatures.”

Warmer nights create a risk, especially in rural and mountain areas where crops reliant on lower temperatures grow and access to air conditioning is limited. Dello says this increase in heat has led to approximately a 6% decrease per year in hours worked in outdoor jobs in the Southeast due to the increased vulnerability of outdoor laborers to heat death.

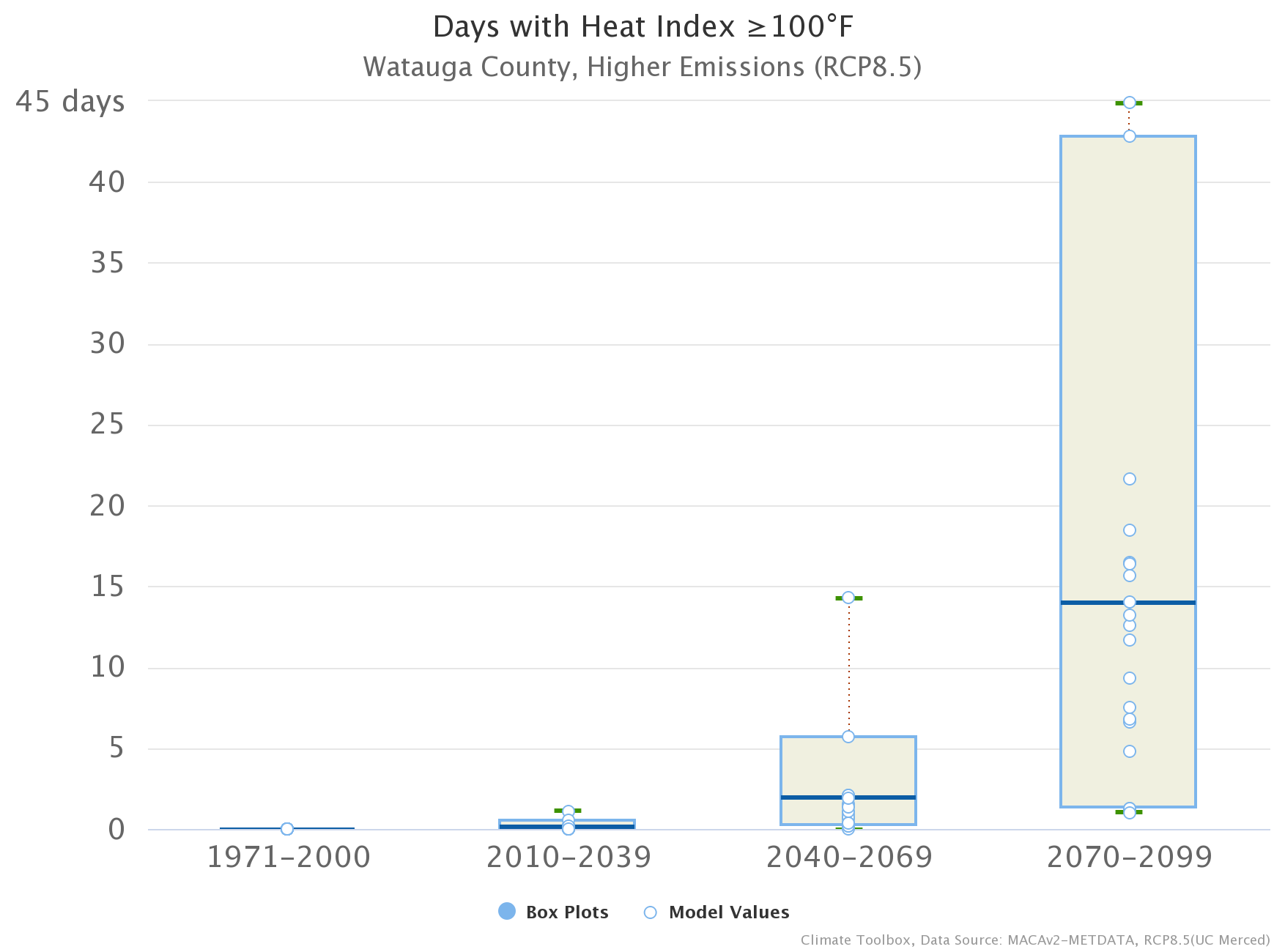

During her lecture, Dello showcased various graphics from Climate Toolbox, a website that visualizes various climate-related projections.

This graphic shows a projection of the number of days where the heat index will be equal to or higher than 100 degrees Fahrenheit in Watauga County, N.C., where Appalachian State University is located, if emissions continue at higher rates. Image courtesy of the Climate Toolbox, data source MACAv2-METDATA, RCP8.5 (UC Merced)

Health Impacts: Disease

Western Carolina University Environmental Health Professor Brian Byrd discussed the importance of preparing for an increase in vector-borne diseases in rural and mountain areas, especially diseases spread by mosquitoes and ticks.

Tick-borne illness is much more prevalent in western North Carolina than mosquito-borne illness. Many of the more common tick diseases such as Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever are bacterial and are cured with antibiotics. However, mosquito diseases such as West Nile virus and La Crosse encephalitis virus cannot be cured with antibiotics.

The La Crosse encephalitis virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes, is the most common mosquito or tick-borne viral disease in North Carolina, according to a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention article by Byrd. Though it is rare, this disease predominantly impacts adolescents, and there is no vaccine, making prevention efforts especially important.

“The challenge is not to overestimate risk and not to minimize risk,” Byrd says. “I’m not trying to fear-monger about this mosquito-borne disease. It’s very rare but it is something, if we can empower people to know a little more about it, there’s a good chance they can do something to reduce their own risk.”

Byrd suggested two strategies to help combat this increase in vector-borne diseases. First, clean backyard debris, which carries an increased disease risk similar to that of forests. Second, people can use many tools which can empower informed choices about personal protection. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Find the Repellant that is Right for You toolbox allows people to find the most effective repellent based on their own personal risks and other factors.

Climate change also impacts rates of vector-borne diseases in ways that aren’t immediately apparent. While the perception is often that increased rainfall leads to increased rates of mosquito diseases, Byrd explains this is not the case. Instead, limited water supplies during droughts force a wider variety of species to congregate in closer proximity at the same water sources, spreading diseases – especially to birds that can carry those viruses longer distances.

“Building Healthcare Access Security During Weather Disasters in Rural Mountain Environments” was one of the seven themes discussed during the event’s workshop portion. Photo courtesy of Maggie Sugg

Health Impacts: Mental and Maternity Health

Maggie Sugg of Appalachian State discussed the ways in which climate change is linked to mental and maternal health. Sugg, a geography and planning associate professor, also hosted the event.

“I like to think of climate change as a threat multiplier,” Sugg said. “It takes those health disparities and really amplifies them, and in rural communities we have really unique health disparities, and so climate change is taking these unique vulnerabilities, these threats, and amplifying them.”

Sugg explained that mental health is often an indirect effect of climate change, such as the negative mental health implications from losing one’s home in a large-scale flood.

In one study conducted with a crisis text line for adolescents, Sugg says there was an immediate 15% increase in texts and a 17% increase in suicidal thoughts in the post-Hurricane Florence storm period.

Some regions of the U.S. showed a correlation between higher temperatures and an increase in suicide rates, though the reason for this relationship is unknown. According to Sugg, this emphasizes the need for grants for local studies and research.

“There’s a lot of studies at the national level talking about climate and health interactions,” Sugg says. “But there’s nothing particular to our area and nothing that really shows us what are the environmental changes for our area.”

One environmental factor with mental health benefits is public green spaces, especially in rural communities. Regional studies in both rural and urban areas in the Southeast found that access to green spaces reduced near-miss mortality in pregnant women, especially Black women. The phrase “near-miss” refers to a woman who survived a complication during either pregnancy or childbirth, according to the National Library of Medicine.

A study in South Carolina showed that exposure of maternal women to floods, particularly during their second trimester, resulted in a 2.43 increase in near-miss mortality rates.

Following the lectures, faculty were divided into seven groups to discuss solutions to different climate change-related issues. The findings from each group will be compiled in a publication to highlight research and grant needs. Photo courtesy of Maggie Sugg

National Impacts: Scientific Assessments

The final speaker at the event, Allison Crimmins, wrapped up the lecture portion by discussing the impacts of climate change on disease, mental health and environmental risks at the national level. These, along with many other findings, will be published in the upcoming Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Crimmins said the NCA5 themes are environmental justice, compounding effects and hope. Compounding effects are “events where more than one hazard interact and cause multiplicatively destructive consequences,” according to the Yale School of the Environment.

One of Crimmins’ examples of this concerned compounding climate, economic and social stressors. There is an overlap in rural communities that are experiencing persistent poverty, as well as places that are expected to see an increased need for air conditioning and cooling due to climate change.

“I can’t tell you the prettiest picture that things are all great,” Crimmins says. “We are facing a lot of threats, but I don’t think we’ve ever been as prepared as we are now either. So I think one of the things that I’m picking up as I’m reading is just how many tools we have, how many communities are already taking actions, how far along the path of mitigation and adaptation we already are.”

The findings from this workshop will be published in a journal article. The NCA5 is scheduled for publication in 2023.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment