Beyond the Tuition Bill, College Students Face Stressful Housing and Utility Costs

By Korie Dean, Energy Democracy Communications Assistant Spring 2021

Kathryn Obenshain was shocked when she received the first electric bill for her off-campus house in September.

Obenshain, who is a junior at UNC-Chapel Hill, moved into the house in August. Based on what they had heard about other students’ utilities costs, Obenshain and her five roommates estimated that, combined, their total utilities would cost about $50 per person each month.

But their September electric bill from Duke Energy came out to $81 per person, or about $485 total.

Obenshain attributes the high bill to the age and condition of the six-bedroom house. She says that there were some spots in the house where air vents were covered by carpet, and large windows on the second floor allowed in so much light and heat from outside that the air conditioning system couldn’t keep up.

“It had always been a student rental,” Obenshain says. “It’s a big place and the zoning for the air conditioning was really bad, because it seemed like everything in the house was an afterthought since it had been a rental for so long.”

Obenshain feels fortunate that she had her parents’ support in paying rent and utilities. But for many college students, utility costs are a burden that is often too much to bear.

“For others in my house that come from different backgrounds, it was scary and frightening,” Obenshain says. “It was like, ‘Okay, well there goes $50 that I might have been able to spend elsewhere for groceries or food.’ We felt completely blindsided.”

A pervasive issue

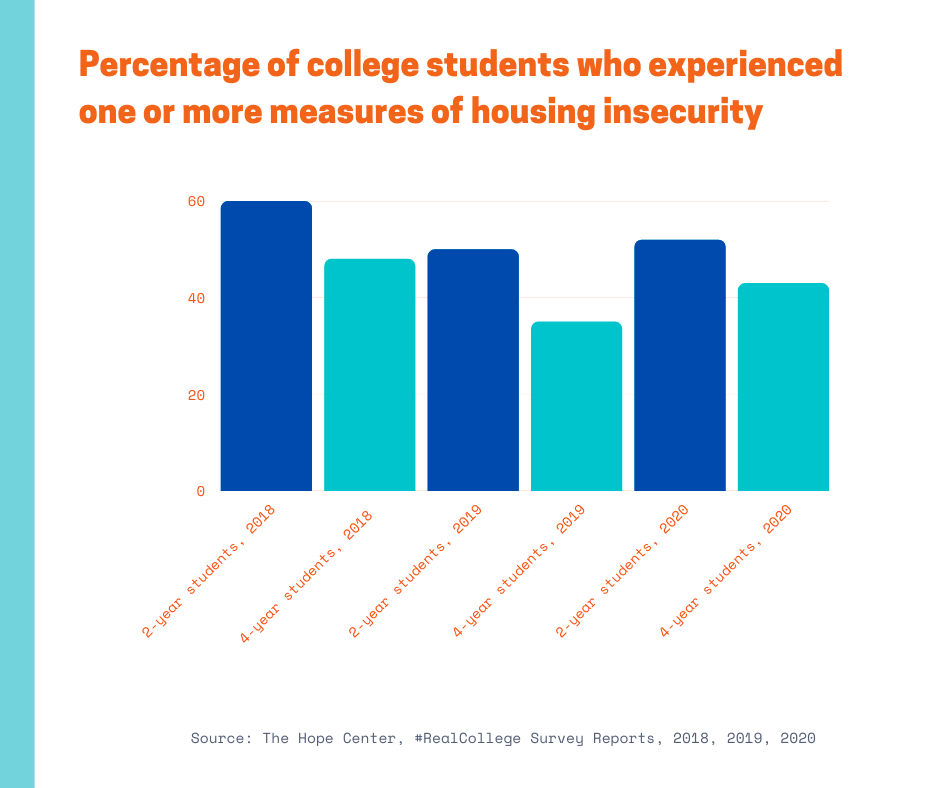

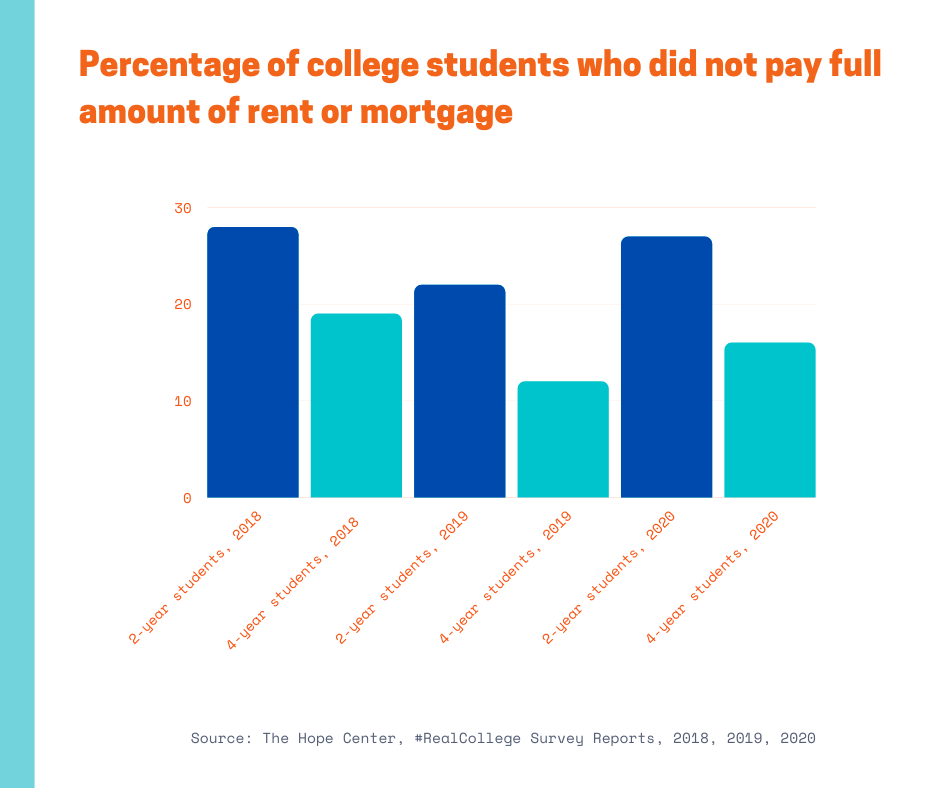

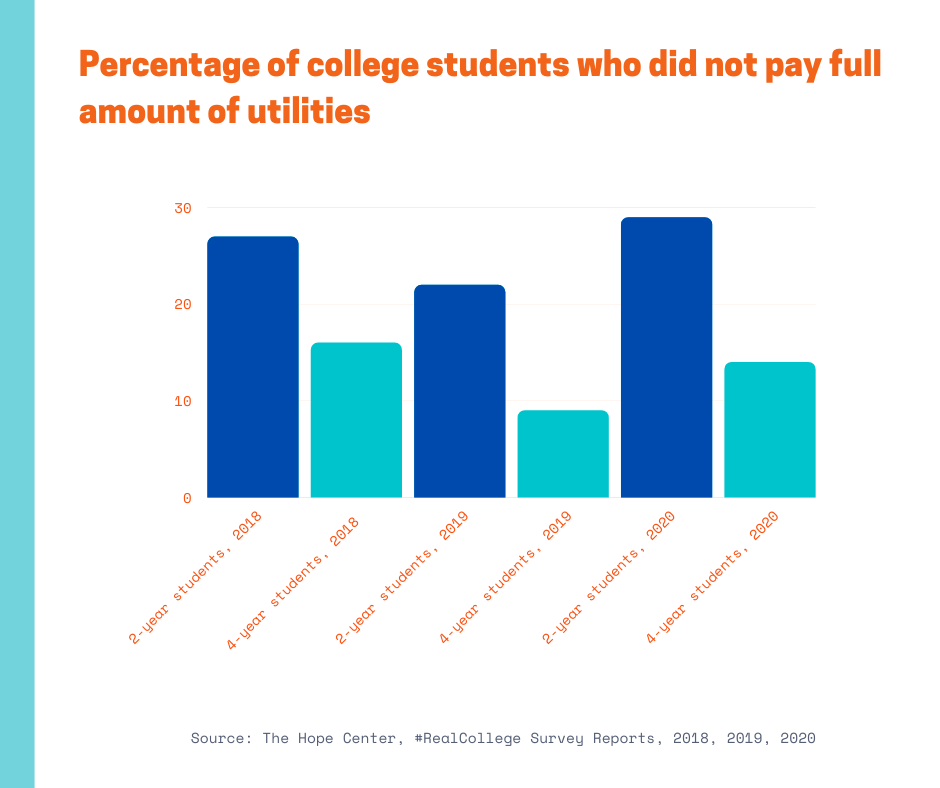

A 2020 survey of more than 195,000 students conducted by the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice found that 48% of respondents faced housing insecurity that year. Of that group, 29% of community college students and 14% of four-year university students could not pay the full amount of their utility bills in 2020.

The Hope Center’s survey also shows that, across both two- and four-year colleges and universities, students of color and LGBTQ students are more likely to experience insecurity around meeting basic needs.

College students aren’t alone in facing housing and utility insecurity. Research from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy estimates that 24% of households nationwide face a high energy burden, which is generally defined as paying more than 6% of one’s income on energy costs.

For college students, who balance their education with part- or full-time jobs and family responsibilities, the financial burden of high housing or utility costs can cause immense stress.

“I’ve had many students in front of me who are thinking of dropping out because they’re so stressed out, and they need tons of assistance to just pay the $200 missing to pay a bill,” says Paula Umaña, the Hope Center’s director of institutional transformation. “It affects their education, it affects their work, it affects their wellbeing because it causes so much stress.”

More than 500,000 students from 500 colleges and universities have participated in the Hope Center’s #RealCollege survey since 2015, making it the nation’s largest and most well-established assessment of students’ basic needs.

Part of the survey’s purpose is to dispel outdated stereotypes about college students.

“Students are no longer what the stereotype used to be,” Umaña says. “They’re not only 18 to 22. They don’t live with mom and dad. Real college students are students who work, who have families, who have to attend to many responsibilities.”

Durham Technical Community College participates in the #RealCollege survey annually. Erin Riney, Durham Tech’s director of student engagement, says that the school’s 2019 survey results showed that 52% of students who completed the survey were housing insecure.

And typically, according to Riney, housing and utility insecurity aren’t isolated issues — they coexist with other financial burdens, leaving students to carefully juggle bills and other financial responsibilities.

In 2019, 32% of #RealCollege survey respondents from two-year colleges and 20% from four-year colleges were both food and housing insecure during that year.

“They’re keenly aware of due dates, and how long things can go before things can get cut off,” Riney says. “They know very well how to manage their resources, it’s just they don’t have a lot of resources.”

While many colleges and universities offer emergency funds and other support services for students experiencing housing and utility insecurity, barriers to access, such as confusion about how to apply for funds, can keep some students from benefitting.

“We weren’t sure if we should talk to someone at Carolina Student Legal Services, or who we should talk to or if it was okay that our electricity bill was so high,” Obenshain says of her September electric bill. “Given the situation, we just felt like there wasn’t a lot we could do. There’s a pandemic going on, so we still have to eat. There’s nowhere else we can go.”

The pandemic’s impact

The pandemic has put an even greater strain on students’ resources, forcing colleges and universities to reevaluate the effectiveness of their financial and social support programs for students.

Maggie West, Durham Tech’s coordinator of student wellness and basic needs, says that she has seen many students lose their jobs because of the pandemic, which has led to many of them moving in with relatives or friends — potentially leading to higher utility bills.

“It feels like an incredible portion of our students’ income has been affected specifically by COVID. Whether that’s reduced hours, or completely laid off from jobs, or having to find different jobs,” West says. “Being homebound during the pandemic, and sometimes with whole families now, all siblings learning at home and parents at home more, the utility bills are also higher than they would be in normal circumstances.”

At the start of the pandemic, Durham Tech implemented weekly wellness calls for students, which has allowed staff to connect students with resources, such as emergency grants or community support networks, on a more regular basis.

While many staff members, such as Riney and West, knew that students struggled with basic needs prior to the pandemic, the increased amount of need over the past year heightened their sense of urgency in responding to the issue.

“Our college has responded to the call of basically what COVID has uncovered, or what COVID no longer allows to be hidden, which is students’ basic needs insecurity,” Riney says. “Those are real and those are here, and COVID just kind of ripped the cover off that. We can’t pretend that they’re not there anymore.”

Many colleges and universities were able to offer emergency financial aid to students through the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, a $14 billion fund established by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act. Students who received HEERF emergency aid could use the money to pay for costs related to tuition, food, child care, health care or housing — including utilities.

Colleges and universities around North Carolina, such as Western Carolina University, Appalachian State University and Durham Tech, received and distributed HEERF funds to students during the fund’s first round of distribution. A second round of HEERF funds became available for universities through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, which passed in December 2020, and a third round from the March American Rescue Plan was made available May 11.

But while increased financial aid and other grants temporarily assist students, fully addressing the financial burden of housing and utility costs among college students is an issue that the Hope Center suggests will take long-term, collaborative efforts between colleges and universities, policymakers and utility companies.

“We need to tell our elected officials that we need help,” Umaña says. “We need help for students. They should get attention.”

Colleges and universities can address the issue on their campuses by being proactive in connecting students with existing resources and assistance programs in their communities and at the state and federal levels, like Durham Tech has done with their student wellness calls.

But the critical first step, Umaña said, is acknowledging the issue.

“Everyone needs to understand that this is real,” Umaña says. “Basic needs are real. It’s not an issue of poverty; it is not an issue of just a few.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment