The End of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline

Sections of the Mountain Valley Pipeline in central West Virginia. Photo courtesy of Mountain Valley Watch

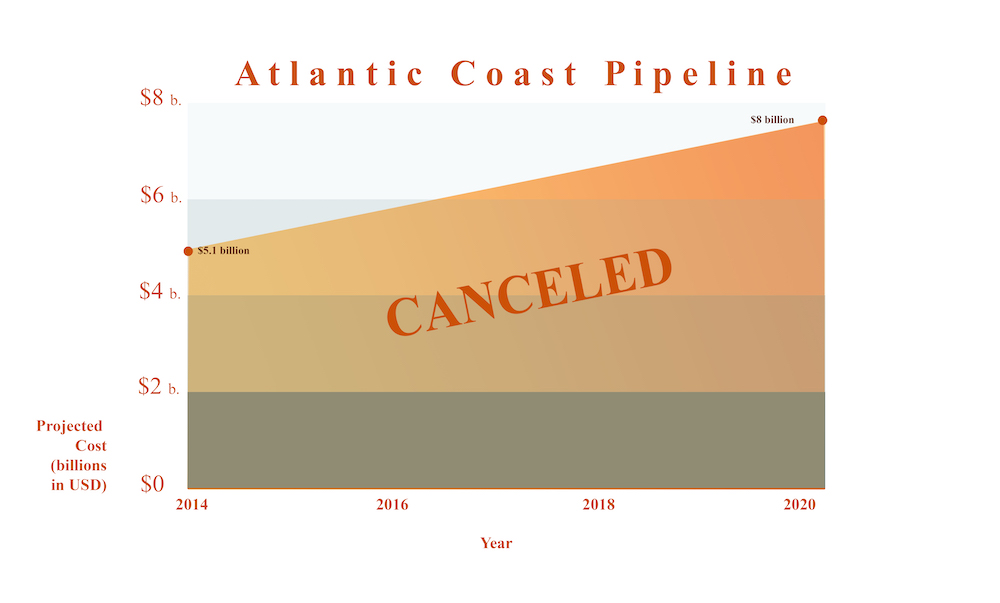

- In a monumental victory for impacted communities, lead developers Duke Energy and Dominion Energy put an end to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline on July 5, citing ballooning costs and increasing legal uncertainty. At time of death, the 600-mile proposed pipeline was nearly $3 billion over budget, three years behind schedule and lacked eight required permits.

- The companies behind the Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley pipelines have spent the past six years arguing that additional major gas infrastructure was needed — but their economic arguments are increasingly coming under scrutiny.

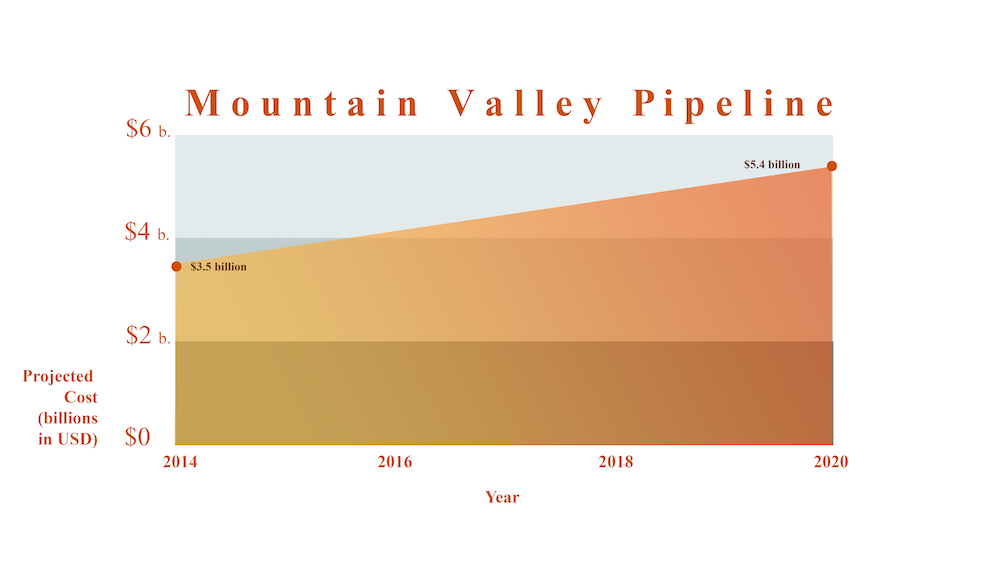

- It remains to be seen how the ACP’s cancellation will affect the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which currently lacks six required permits, is nearly $2 billion over budget and is more than two years behind schedule.

- Duke and Dominion continue to claim that there is a “robust demand” for natural gas in the region.

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline is no more.

On July 5, lead developers Dominion Energy and Duke Energy sounded the death knell for the 600-mile fracked gas behemoth, citing ongoing delays, increasing costs and legal uncertainty. This is a monumental victory for the North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia communities in the path of the pipeline that spent the better part of a decade fighting against it.

Following legal challenges from community and environmental groups, construction has been halted on the largely unbuilt pipeline since late 2018, and developers lacked eight permits at the time the project was canceled. Although Duke and Dominion won a Supreme Court case in June that would have allowed them to burrow under the Appalachian Trail, this was not enough to overcome the variety of obstacles the monopoly utilities faced.

The Friends of Buckingham in Union Hill, Va., were one of many groups opposed to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Photo by Lara Mack

“I feel that all the hard work that all of us have done was finally for good,” said Ella Rose with Friends of Buckingham in a statement. “I feel like I have my life back. I can now sleep better without the worries that threatened my life for so long.”

Bishop William Barber II and former Vice President Al Gore spoke at a rally against a proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline compressor station in Union Hill, Va., in 2019. Photo by Cat McCue

In addition to canceling the ACP, Dominion announced the sale of $9.7 billion in gas transmission and storage assets to Berkshire Hathaway Energy on July 5. The sale does not does not include the Atlantic Coast Pipeline or easements related to it.

On July 10, Dominion asked federal regulators for an additional two years to complete their supply header project, a 30-inch-diameter pipeline which would have stretched about 38 miles from West Virginia’s fracking fields to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. But the justification behind finishing the project is unclear, according to Thomas Hadwin, a former utility executive. Hadwin now sits on the steering committee of the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance, a coalition of 51 organizations including Appalachian Voices that opposed the ACP.

“Without the ACP, the supply header project is sort of a bridge to nowhere, because there’s no pipeline connected to it,” says Hadwin. “Since that was the source of the ACP, it would have the potential to supply the volume of gas that was going to supply the ACP.”

The supply header was 31 percent complete at the time of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline’s cancellation, according to Dominion.

The company is also seeking a one-year extension to work along the ACP route on site restoration.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission set a 15-day public comment period on the two requests, which ends at 5 p.m. on Aug. 3. Attorneys with the nonprofit law firm Southern Environmental Law Center asked FERC to deny the request for an extension to complete the supply header project, arguing that it does not meet FERC’s standards for time extensions, according to The Recorder. SELC attorneys stated that another comment period of 30 days was needed “to highlight the concerns of landowners, conservation groups, and other stakeholders.”

Dominion plans to end around 80 eminent domain lawsuits with residents who had opposed the utility’s attempts to use their land for the pipeline, according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

“We will evaluate the best way forward for resolving easement agreements with landowners,” a Dominion spokesperson told the Times-Dispatch. “They will, of course, keep any compensation they’ve received.”

The private companies behind the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the unfinished Mountain Valley Pipeline have spent the last six years stating that new fracked-gas infrastructure is needed to meet rising gas demand, a claim that pipeline opponents had refuted. And the economic challenges have grown since the projects were announced in 2014.

Since the projects’ start, economic experts have warned of an overbuild of natural gas infrastructure and stated that existing pipelines would be sufficient. And global demand for natural gas could fall 5 percent in 2020, the steepest decline in 70 years, according to an April report from the International Energy Agency.

The cost of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline rose by nearly $3 billion by the time Dominion Energy canceled it. Graphic by Hayley Canal

If the Atlantic Coast Pipeline had been built, these costs and others would likely have been reflected in customers’ monthly utility bills — further increasing the amount of a person’s income spent on electric bills.

In a June 2019 letter to North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, NC WARN’s Jim Warren warned that the pipeline’s cost to state ratepayers could be much greater than anticipated. The letter was sent on behalf of Energy Justice NC, a coalition of 15 local, state and national groups including Appalachian Voices. After including the construction, financing and operating costs in addition to the pipeline’s 15 percent rate of return, North Carolinians would have paid more than $20 billion for the ACP over 20 years — regardless of how much gas was used. This amounts to 66 percent of the ACP’s cost.

The cost of the Mountain Valley Pipeline has risen by nearly $2 billion in the last several years. Graphic by Hayley Canal

In May, financial analysts told Reuters that MVP Southgate would be more likely to be built in the case of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline’s cancellation. Even so, the future remains unclear for both the Mountain Valley Pipeline and its proposed extension.

Maury Johnson with grassroots coalition Protect Our Water, Heritage, Rights, celebrated the July 5 victory over the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, but stated that the job is only half-finished. Johnson lives in the path of the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

“Today we enjoy this victory, but tomorrow we must double down our efforts, pull together and send MVP and the MVP Southgate to the scrap heap of bad ideas with the ACP,” said Johnson in a statement.

What’s Next?

Now that Duke and Dominion have canceled the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, what will happen with the Mountain Valley Pipeline? Developers stated in June that the project is 92 percent complete, with approximately 80 percent of pipe in the ground and about 50 percent of site restoration finished.

Mountain Valley Pipeline sections and a cleared right-of-way in Craig County, Va., in May 2020. Photo courtesy of Mountain Valley Watch

Nancy Bouldin with the grassroots group Indian Creek Watershed Association said over email that “even more important than the number of miles left is the fact that these miles are among the most difficult and vulnerable miles of the route — almost all stream and wetland crossings, many with extremely steep approaches on one or both sides and all presenting unique challenges.”

Appalachian Voices’ Virginia Program Manager Peter Anderson notes that issues related to the Endangered Species Act — which led FERC to order a halt to construction in October 2019 — may be difficult to resolve.

“MVP’s permits under the Endangered Species Act were rushed and slipshod, and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the government to reconsider the pipeline’s impacts on species and their habitats,” says Anderson. “Sediment pollution from construction has been so severe, it could be quite difficult for the agencies to show how the project complies with that law, especially with the endangered Roanoke logperch living along its route.”

In June, Mountain Valley developers pushed back the completion date of the pipeline yet again, this time from late 2020 to early 2021. The company stated the delay was due largely to permit disputes for crossing waterbodies, the Jefferson National Forest and the Appalachian Trail.

But a July 6 U.S. Supreme Court decision may clear the path for Mountain Valley developers to build across waterbodies by reopening the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Nationwide Permit 12 program, which allows regulators to grant blanket water-crossing permits instead of individual reviews. A federal district court judge in Montana closed the program in April, stating that the government had violated the national Endangered Species Act by not undergoing proper review with wildlife agencies before approving the Keystone XL Pipeline. And the Supreme Court’s June decision allowing the now-canceled Atlantic Coast Pipeline to cross the Appalachian Trail clears an additional barrier for MVP developers.

Even with the Nationwide Permit 12 generally in place, however, Mountain Valley Pipeline developers already lost verifications of the permit in three different geographic regions to a court order and agency suspensions. Developers will need agencies to reinstate those permit verifications before the pipeline can cross water bodies. Additionally, MVP’s overall project certification from FERC expires in the fall, and developers have yet to ask for an extension. Added on are the hundreds of environmental violations reported by citizen monitoring groups as well as a tree-sit in the path of the pipeline that has been ongoing for nearly 700 days as of mid-July.

Investor Doubt

Investor confidence in the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was cracking in the months leading up to the July cancellation of the project due to the multitude of legal barriers facing the project. The same holds true for the embattled Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Back in February, Dominion bought out the 5 percent share in the Atlantic Coast Pipeline held by Southern Company Gas. Investment banking firm Morgan Stanley expressed doubt that the project would be completed.

As for the Mountain Valley Pipeline, Con Edison — which owns approximately 10 percent of the project — capped its investment in the project at $530 million in late 2019. Lead developer EQM Midstream Partners took on an additional $86 million burden around the same time. EQM’s stock price has decreased by roughly 80 percent since announcing the pipeline in 2014.

A section of the unfinished Mountain Valley Pipeline near Virginia’s Brush Mountain in July 2020. Photo courtesy of Mountain Valley Watch

In 2015, Roanoke Gas pledged more than $50 million to Mountain Valley to acquire a 1 percent stake in the pipeline. But the cost could be much more than that, according to former utility executive Thomas Hadwin.

In a September 2019 op-ed in The Roanoke Times, Hadwin wrote that Roanoke Gas will have to pay at least $71 million to reserve space on MVP over the next 20 years — even if the company does not use the pipeline.

“Escalating prices for the delayed pipeline will make the cost of that contract closer to $100 million,” he wrote. “Roanoke Gas intends to spread these higher costs among its existing customers.”

Roanoke Gas’ current supplier and another nearby pipeline could both exceed the amount of gas that the Mountain Valley Pipeline could offer to Roanoke Gas, and are available at a much cheaper rate, according to Hadwin.

Five companies that have contracts with the Mountain Valley Pipeline had the option to withdraw in June since the project was not in service by June 1, 2020. However, none of the five companies exited the agreement, according to The Roanoke Times.

A Question of Need

Sections of the Mountain Valley Pipeline in Craig County, Va., in May 2020. Photo courtesy of Mountain Valley Watch

At the time, Dominion planned to build two large gas-fired plants and Duke planned to build six. This potential market demand was used to justify both pipelines as well as the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline to FERC, wrote Thomas Hadwin in a January 2020 report. The Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline began transporting fracked gas in 2017.

“[FERC] was aware that three pipelines were vying for the same market, but they applied no comprehensive analysis to determine which project might best meet the need,” wrote Hadwin. “Instead, they approved all three projects.”

In 2018, Dominion told Reuters that they had no further plans to build large baseload gas plants due to the low cost of solar. This is reflected in their May 2020 long-term plan.

Now, even though Mountain Valley Pipeline construction has already scarred hundreds of miles, more than 99 percent of the gas that would flow through it does not have an end user buyer, according to Hadwin. He states that customers will be difficult to find given that gas can be delivered much more cheaply from the existing Transco pipeline, which stretches more than 10,000 miles from the Gulf Coast to the northeast. While the MVP is supposed to connect to this pipeline, Transco developers have already completed other extensions such as the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline.

If Dominion and Duke had built the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, it could also have been underutilized, according to Greg Lander, president of energy consulting company Skipping Stone. In June 2019 testimony to Virginia regulators on behalf of Appalachian Voices, Lander stated that Dominion’s own data showed that the company had sufficient pipeline capacity for its existing and future needs.

The future of gas-fired power in the commonwealth became bleaker in spring 2020 with the passage of the Virginia Clean Economy Act, which mandates that all of Dominion’s and Appalachian Power’s carbon-emitting power plants, including gas-fired power plants, close by 2045. It also requires regulators to consider the social cost of greenhouse gas emissions when evaluating utility proposals for new power plants.

Another new law requires Virginia electric utilities looking to build significant natural gas infrastructure to prove that new pipelines and facilities are needed to meet electricity demand, and that it is the most cost-effective option for ratepayers. This makes it much harder for Dominion to justify putting electric customers on the hook for large amounts of new gas pipeline capacity such as the ACP to state regulators.

The recent legislation means it’s no longer viable for Dominion to plan on generating a significant amount of its electricity from new gas-fired power plants. In its latest long-term plan, released in May after the laws were signed, Dominion dropped its estimated need for new gas-fired units by nearly 75 percent.

In fall 2019, Duke submitted a plan to state regulators that included a projected need for the construction of up to 14 new gas-fired power plants in the Carolinas by 2034. Environmental advocates argued that these plans clash with Duke’s goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Duke’s shareholders held CEO Lynn Good’s feet to the fire in a May quarterly earnings call. Several investors asked Good why the company was still investing in major gas-fired power plants and the Atlantic Coast Pipeline when Duke had a 2050 net-zero carbon emissions goal.

Both Duke and Dominion hold that there continues to be a “robust demand” for natural gas in the region post-Atlantic Coast Pipeline. In July, a Duke spokesperson told the Charlotte Business Journal that the company is evaluating the possibility of adding additional natural gas infrastructure in eastern North Carolina. Specifics should become clear after Duke releases their long-term plan in September.

While it remains to be seen just what will happen with the Mountain Valley Pipeline and whether Duke will transition away from natural gas to renewables, environmental groups and communities in the path of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline are cheering the defeat of the 600-mile behemoth.

“From Robeson County, N.C., to Harrison County W.Va., in statehouses and courthouses, communities have stood shoulder to shoulder to protect their land, their water and their communities,” said Appalachian Voices’ Executive Director Tom Cormons in a July 5 statement. “We are hopeful that this momentous victory is merely a tipping point as our society pivots towards a clean energy economy that works for all people.”

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment