Changes for MVP Southgate Pipeline are Part of a Web of Proposed Methane Gas

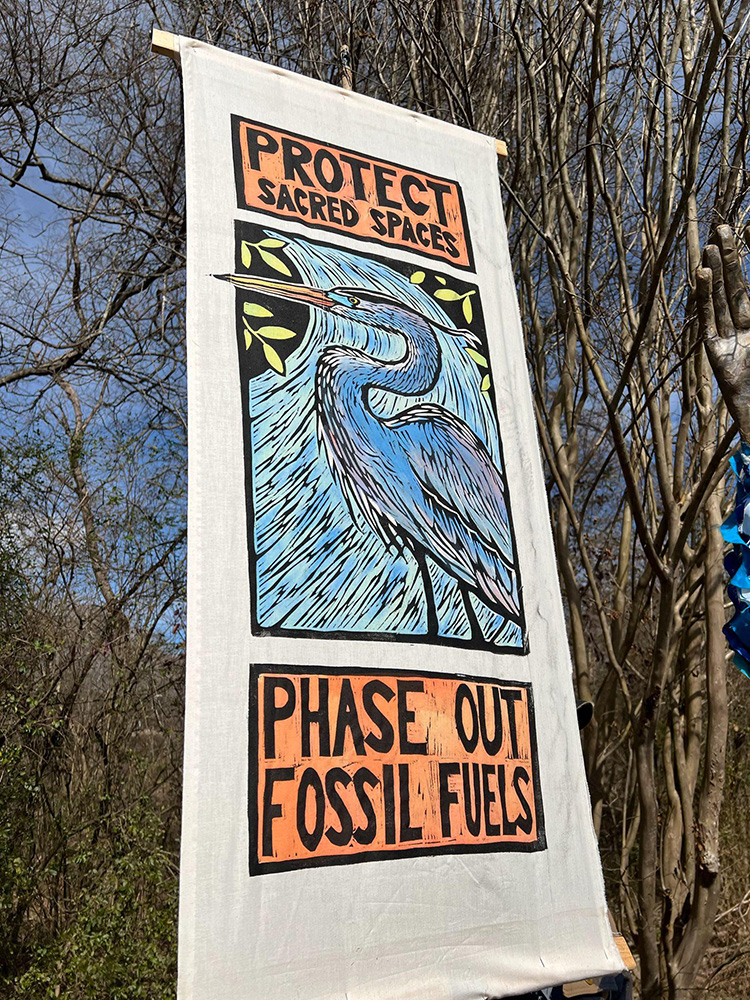

7 Directions of Service leads a Water Walk in February near the route of MVP Southgate. Photo courtesy of 7 Directions

By Jen Lawhorne

At the end of 2023, Equitrans Midstream, a company behind the Mountain Valley Pipeline, announced a dramatic change in plans for its Southgate extension that would reduce the length of the pipeline but increase how much gas it would carry. The announcement came less than two weeks after the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission granted the project permission to build for another three years.

This came despite a groundswell of public opposition including comments and petitions from tens of thousands of members of the public, letters from dozens of legislators at the state and federal levels from North Carolina and Virginia, and N.C. Governor Roy Cooper asking FERC to deny MVP’s request for another three years to build Southgate.

“MVP Southgate changed its plans because of the delays that our organizing was causing,” says Kasey Kinsella of 7 Directions of Service, an Indigenous-led group that works to protect the rights of people and nature in North Carolina. “We’ve proved that our base building and mobilizing is effective.”

Haw Riverkeeper Emily Sutton agreed. “I sincerely believe that the change is a direct result of the strength, perseverance and resilience of our impacted communities and team of advocates,” she says.

In late April, a number of conservation groups including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper, filed a petition in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit challenging FERC’s decision to grant Mountain Valley Pipeline’s Southgate project the additional three years.

Construction for the MVP Southgate extension, which was planned to run through a southern Virginia county and two North Carolina counties, never began. The pipeline was proposed in 2018 but was denied permits from state agencies and failed to acquire land through eminent domain in North Carolina.

So pipeline opponents were puzzled by Equitrans Midstream’s announcement on Dec. 29 that it planned to reduce MVP Southgate from 75 to 31 miles and cut down on the number of water crossings for the pipeline by removing North Carolina’s Alamance County from the route, as well as dropping plans for a compressor station in Pittsylvania County, Virginia.

Maps of the newly proposed route were not available as of press time in April, so it’s unclear how many new landowners and water crossings would be directly impacted by the change. Mountain Valley has said the new design would provide up to 550,000 dekatherms per day of gas capacity, a significant increase from the original capacity of 375,000 dekatherms per day. That means more pressurized gas would flow through, and the new plans for Southgate would con- tribute to more fracking and more emis- sions at power plants than the original.

“[MVP Southgate] was ballooning in costs and there was no longer a feasible return on investments [for Equitrans Midstream],” said Sutton. “Those ballooning costs were a direct result of delays from denied permits, local government resolutions to oppose the project, lack of access for surveying, eminent domain fights and environmental justice wins.”

Virginia authorities rejected a permit for Southgate’s Pittsylvania compressor station in 2021, while the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality twice denied MVP Southgate a crucial water quality permit.

Although the MVP Southgate extension is no longer crossing Alamance County, where the Haw River is located, community organizers were not calling this change a win.

“Initially, we felt relief for the communities in the Haw River watershed that have been fighting this proposed project alongside us for six years,” Sutton says. “When we more fully understood the proposed plan was not canceled, but rerouted to other communities, I immediately contacted our other partners in the Waterkeeper movement to make sure they had the tools and resources and support they needed to help the newly impacted communities.”

“The process of constructing a fracked gas line [poses] serious dangers that no community should be exposed to for corporate greed and fossil fuel expansion,” Sutton adds. “We can not allow fossil fuel companies to continue to designate communities of our friends, family and neighbors as sacrifice zones.”

Kinsella noted that while Southgate would no longer cross the Haw River, the Haw is connected to the Dan River, which would be crossed by the pipeline.

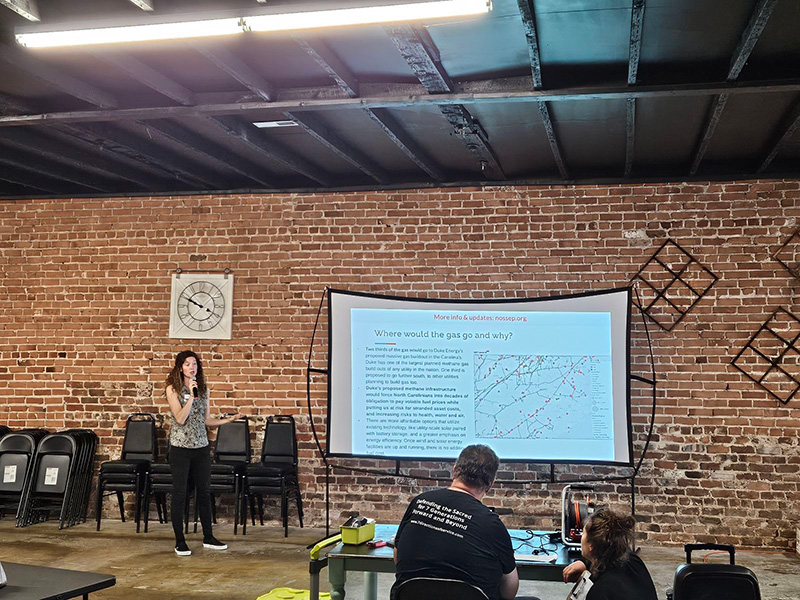

Sierra Club Senior Field Organizer Caroline Hansley shares information with landowners potentially impacted by the Southeast Supply Enhancement Project. Photo by Jessica Sims

“All of our water and all of our fights are connected. We’re facing a number of new fracked gas expansion proposals, like the Transco Southeast Supply Enhancement Project pipeline and T-15 Project, on our plates,” Kinsella says. “We’re evaluating the landscape and our strategy moving forward.”

The Transco Project is a nearly 55-mile pipeline that would cross through Virginia and North Carolina with additional compressor units. Dominion Energy’s T-15 Reliability Project is a proposed 45-mile pipeline within North Carolina from Eden, the terminus of the proposed MVP Southgate line, to Hyco Lake. Because T-15 would be entirely within North Carolina, it doesn’t need federal approvals, and a state law passed in 2023 dramatically weakened North Carolina’s pipeline review process.

On the shores of Hyco Lake, Duke Energy wants to use the gas from MVP Southgate and Williams Transco to convert the Roxboro Steam Station, a coal-fired power plant, to run on methane gas instead of pursuing clean energy. Duke is proposing the Roxboro plant conversion to gas as part of a massive uptick in electricity generated from fossil fuels.

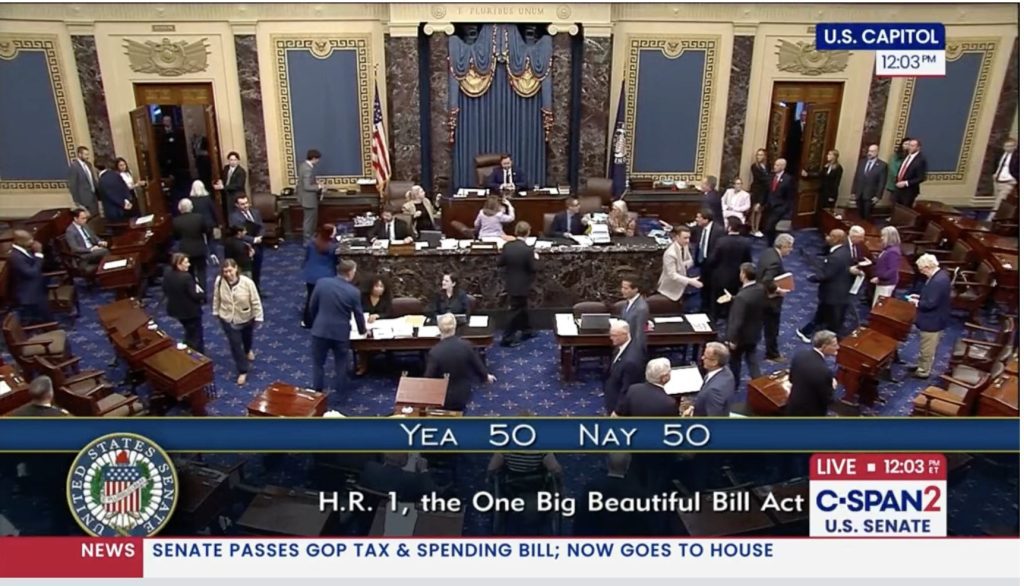

The utility giant is required by North Carolina law to regularly update its Carbon Plan to reduce fossil fuel emissions. Duke’s 2024 proposal for North and South Carolina calls for nearly 9 gigawatts of new gas by 2035 — almost three times the amount proposed in the original 2022 Carbon Plan.

“Duke Energy’s latest attempt to expand our reliance on methane gas is moving North Carolina in the opposite direction of where we need to go,” said Ridge Graham, North Carolina Program Manager with Appalachian Voices. “Families and farmers are being asked to sacrifice land, health and peace of mind for projects that are less reliable and affordable than renewables.”

Additionally, in Person County, N.C., Dominion Energy has proposed a 25-million-gallon liquified natural gas storage facility called Moriah Energy Center, which would also emit air pollutants.

But Kinsella noted these new proposed projects won’t slow down the community organizing that groups are doing to build a movement against fracked-gas projects in the region.

“We’re going door-to-door and connecting with impacted folks, landowners and community members,” she says. “We’re building community around our opposition.”

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *