The Appalachian African American Cultural Center

Jill and Ron Carson sit in front of a few historical artifacts collected over the years. Prominently displayed is an old photograph of Ron’s great-great-grandmother Rachel Scott, below, who built the building in 1939 as a school for African Americans. Photo by Kevin Ridder

For 25 years, the building was the only school for local African Americans up to 8th grade until Lee County integrated its public schools in 1965. Ron Carson, who obtained the building and founded the cultural center in 1987 with his wife Jill, has deep ties to the former schoolhouse.

“My mother was in the first group in this building in 1940, and I was the last group before integration in 1965,” says Ron Carson. “My great-great-grandmother, Rachel Scott, built this building in 1939 with $16,500.”The walls of the Appalachian African American Cultural Center are lined with old photos, historical documents and more. Prominently displayed is a black-and-white photograph of Rachel Scott in a thick, black frame above various class photos of schoolhouse alumni. Ron Carson states that it’s common for locals to visit the center and spot a photo of their parents or grandparents on the wall.

The Carsons have spent decades building their collection with the community, and say they are happy to give anyone a personal tour with an appointment. They have conducted Black history programs for local schools in the past, and Ron Carson says student groups often visit during Black History Month in February. The center also hosts workshops on dismantling racism.

“What we thought we’d do is try to pull some of those decision-making people, bring them all together in a safe place and talk about, once again, ‘How can we heal this world?’” says Ron Carson. “We’re trying to heal the world, to get people to talk about it. Because if you don’t reveal, you can’t heal.”

Visit or Donate to the Center

Appalachian African-American Cultural Center

230 N. Leona St., Pennington Gap, VA 24277

To schedule a tour, call (276) 346-5144

Federal judges, lawyers, doctors, teachers, principals, religious leaders and more have attended these workshops. Sue Ella Kobak, a retired lawyer who was once the Lee County attorney, has participated in several.

“I’ve attended five [workshops], and every time a part of me — kind of the inherent racism — is revealed to me,” says Kobak. “It’s like peeling away an onion. I recognize something else I’m doing or saying or thinking that needs to be challenged.”

Kobak, whose father was a coal miner in Eastern Kentucky, helped the Carsons save the schoolhouse from demolition before it became the cultural center. She states that the center has greatly increased her awareness of Black history in the region.

“I’ve learned so much, just with my association with the cultural center in the last 30-plus years,” Kobak says. “I think [the center] helps the community because it provides a broader picture of who and what Pennington Gap is. The fact that the center exists is a powerful symbol. I think it makes it impossible for the community to ignore the presence of people of color in this region.”

A History

One of the last student groups to be taught in the schoolhouse before Lee County, Va., integrated in 1965.

“They had church on Sunday, and Monday through Friday it was a school for the Black kids,” says Ron Carson. “Just recently, we found documents from the Library of Congress where the principal of the school wrote Thurgood Marshall, who was working for the NAACP in Richmond, Va.,” he says, referring to the future U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

“There were holes in the roof, the windows were falling out and it was cold in the wintertime, so they asked if they could have assistance to renovate the building,” Ron Carson continues. “Well, obviously it didn’t happen, and as a result my great-great-grandmother built this building so the kids would have some type of a school.”

Even with the new building, however, the school was sorely lacking comforts.

“It didn’t have a bathroom, we had outdoor toilets,” says Ron Carson. “All of this was cowpastures. We didn’t have any playground equipment; parents took old socks, rolled them up and sewed them into a ball and we played sockball right out there on the lawn with broom and mop handles.”

On their way to school each morning, Ron Carson and his classmates would pass three large buildings that comprised the town’s White school. One of the structures, a prominent building with four white columns, has since been converted into a local bank on Pennington Gap’s main street.

“We always wondered why the White kids had playground equipment,” says Ron Carson. “You really didn’t know any better. This is what we had.”

Integration

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. However, it took 11 years for Lee County, Va., to integrate — not uncommon for school systems in the South. It might have taken even longer for the schools to integrate without the proactiveness of local doctor Eddie Beaty, according to Ron Carson

“We all met at the church, and he pretty much led the integration and said, ‘It’s time for you kids to go to the White school,’” he says. “So all the parents, all the kids, we met in downtown Pennington Gap and we all walked out to the school and integrated it.”

“They knew we were coming that Monday morning in August of 1965,” he continues. “The principal was standing there at the front door. As we walked in, he said, ‘I’m wondering what took you so long to get here.’ I thought, ‘Well, you didn’t invite us.’”

To Ron Carson, walking into Pennington Gap High School after receiving most of his education in a one-room schoolhouse “was like walking onto the campus of Yale University or Harvard.”

Saving the Schoolhouse

After graduation, Ron moved to Boston, where he met his wife Jill. Ron Carson, now retired, began the black lung treatment program at Stone Mountain Health Services in Southwest Virginia and has been recognized by Congress for his work. Jill Carson is currently in her second term as a Pennington Gap councilwoman — the first African American woman to hold the office.

“When we decided to move back here in 1986, the schools were being consolidated, and this little one-room school was still being used by the Lee County school system,” says Ron Carson. “But by consolidating schools, that meant they had no further use for this building and they were going to tear it down and send [the land] off to auction. I just knew that it was special to me.”

“Every year when we would come home for the summer to visit our parents, we’d come here and look in the window just to reminisce a little bit,” he adds. “I knew, and I convinced my wife, that we had to do something to preserve this building.”

Obtaining the building was challenging. Jill Carson states that although Ron’s great-great-grandmother built the schoolhouse, the deed did not include a clause about returning the building to the family.

“We tried to get the county to save the building, to not auction it off, to think about giving it back to the community,” Jill Carson says. “It wasn’t easy, we really had to go to battle for that. At the time that we moved back here, there were less than 100 Blacks in a county of some 25,000.”

Jill Carson knew they would need outside help. So, she reached out to the NAACP in Bristol, Va., for legal assistance. The story was picked up by local media, and the county eventually handed over the property under the condition that it could still be used as a polling location.

Filling the Walls

This guitar belonged to the late Dickenson County, Va., musician and coal miner Earl Gilmore, a devout Christian who came out as gay towards the end of his life. He led his church choir, performed with renowned musicians and traveled internationally until his death in 2000. Learn about an upcoming documentary on Gilmore at BecauseImHere.com. Photo by Kevin Ridder

“We were part of the SALT program, the Southern Appalachian Leadership Training program,” says Jill Carson. “We’d go there every weekend and sit with people from everywhere, and we found out that little if anything had been written about African American people in the Appalachian region.”

Ron and Jill Carson knew that they had to act quickly to preserve the experiences of the county’s Black population.

“We knew that the African American community here was an aging community, and it was small to begin with,” says Jill Carson. “We were on a mission.”

Once the Carsons decided to turn the building into a cultural center, they held a community meeting at Ron’s parents’ house. Jill Carson states that Black and White community members were very receptive to the idea.

“We decided from that point that we’d have memorabilia nights,” she says. “We’d have it right here and ask people to come and bring something, anything that they had.”

Slowly, the Carsons began to amass a collection of photos, documents, handwritten stories and more, some of which they hung on the walls after opening the center in 1987. Then, after an election in the early ‘90s, the county board of supervisors informed the Carsons that someone had complained that there were political materials on display — specifically a photo of Doug Wilder, a former Virginia governor and the first African American governor elected in the history of the country.

“We tried to explain to them that we weren’t making a political statement, just that we felt he’d earned a place in this building,” says Jill Carson. “After that, what we decided to do was to take everything down when there was an election.”

The Carsons would store all the center’s memorabilia in a small room with a window. But in October of 1994, there was a fire in that room.

“We lost everything, because everything was in one place,” says Jill Carson. “Something came through that window and just engulfed that whole area back there and spread out here. The whole inside burned.”

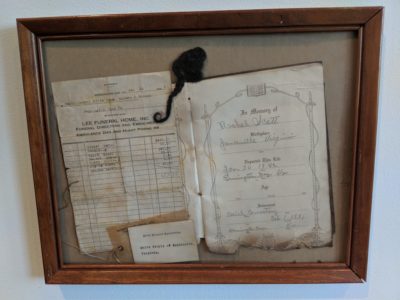

Rachel Scott’s funeral program, singed at the edges, is the only thing that survived the 1994 fire at the cultural center. Photo by Kevin Ridder

“Something came through the window,” he says.

The only item that survived the fire was a program from Rachel Scott’s funeral.

“We felt that was her telling us, “Ok, I’m leaving this here for you, God left it here for you. Move forward,’” says Ron Carson.

Onward

After the fire, the Carsons requested other materials from the community to try and reclaim some of the history that had been lost — and the memories flooded in and filled the building’s walls again. The county also stopped using the center as a polling location.

Working with the grassroots multimedia cultural center Appalshop, based in Whitesburg, Ky., the Carsons started hosting regular story swaps in the mid-’90s. The couple also started recording oral histories with the elderly Black community, collecting more than 50 video and audio recordings that they have started to digitize. Ron Carson states that these people, some of whom were born in 1899 and 1900, are all gone now.

“The father of Black history once said, ‘Perhaps the most important element to any given people is the documentation and preservation of their own history. If its race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition and it stands to be lost in the eyes of society forever,’” says Ron Carson, quoting Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

“Everything we do, we do with that [idea] as a foundation,” Jill Carson adds. “We started out with one specific goal, but it has branched out because we think it’s important for everybody to know who they are and to have a strong foundation.”

This article is the first in a series of stories exploring the experience of African Americans in Appalachia. Upcoming articles will feature efforts to preserve Black cemeteries and the story of the Eastern Kentucky Social Club. If you would like to share information regarding these or other articles in the paper, please email voice@appvoices.org.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment