Pay-What-You-Can Cafes

By Dave Walker

F.A.R.M. Cafe staff member Tommy Brown, at front, works with volunteers to prepare donation-based lunches for diners. Photo courtesy of F.A.R.M. Cafe

“This restaurant model is about doing things differently — a different value system,” says Tommy Brown, volunteer and development coordinator at F.A.R.M. Cafe in Boone, N.C. “We’re not about profit. It’s really about change, about helping people.”

Twenty community members began planning F.A.R.M. Cafe in 2009. The project originated like many other donation-based cafes: someone in the community heard of Denise Cerreta’s pay-what-you-can One World Cafe in Salt Lake City, Utah. The local group began to meet monthly and researched similar cafes. In January 2012 they leased a landmark former soda fountain in downtown Boone and opened F.A.R.M. Cafe, which stands for “Feed All Regardless of Means.”

In Boone as well as South Charleston, W.Va., Wytheville, Va., Johnson City, Tenn., and Danville, Ky., pay-what-you-can restaurants are breaking down the barriers of how people typically interact with a restaurant, while supporting local farmers and healing communities.

There are at least five donation-based restaurants operating in Appalachia offering a range of services from hot bars to catering. Still more cafes are in the planning and development phases.

Volunteers

Volunteers power this model by preparing and serving food and cleaning up the restaurant at the end of each day. Volunteers also break the boundaries within the restaurant — a volunteer could be a retiree, a student or someone in need of a hot meal.

“The right folks walk in the door every day,” says Michelle Watts, executive director of One Acre Cafe in Johnson City.Volunteers greatly outnumber staff at Appalachia’s pay-what-you-can cafes. F.A.R.M. Cafe’s weekday meals are 90 percent created and served by volunteers, and in Wytheville at Open Door Cafe, as many as 20 volunteers work alongside the two staff members each day.

Volunteers are the biggest challenge and the greatest fulfilment according to Renee Boughman, executive chef at F.A.R.M. Cafe. Every day requires fresh introductions to how the restaurant operates, where serving utensils are located and how to wash dishes. Boughman says that volunteers become invested in the space and the model. In 2018, more than 3,750 people volunteered at F.A.R.M. Cafe to help serve 17,681 meals.

“They’re giving their time, but they’re often surprised that they enjoy it,” says Boughman. “They’re surprised about the community here. Then, they come back. They care about this place.”

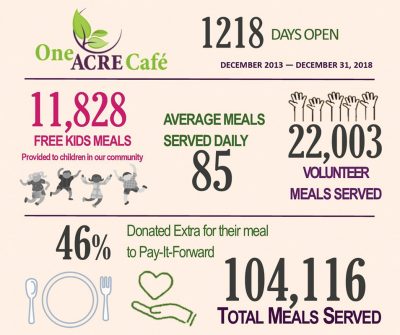

After each one-hour shift, volunteers at the pay-what-you-can cafes receive a meal, comprising a significant percentage of the restaurants’ patrons. Since December 2013, One Acre Cafe has served over 104,000 meals with more than 21 percent had by volunteers.Johnson City, like Boone, is a university town.

“We have such a blending of folks who come into One Acre Cafe,” says Watts.

These people include college students who need volunteer hours or who do not have funding for food, veterans from the VA hospital, local residents facing challenges and neighbors who are able to share their time and donations.

“It’s not just a free meal,” says Watts. “We encourage people to participate however they are able to do that. We want to truly be a community cafe, taken care of by the community.”This approach challenges the traditional way that the public goes to restaurants and participates in community, which entails a blurring of who prepares and serves the food and who consumes it.

Staff at each of these donation-based restaurants explain that their cafes are based upon uplifting each other and forming connections. In Boone, tourists sit next to and talk with individuals living out of their cars. In Johnson City, university professors serve food alongside food-insecure students.

“They’re just sitting having conversation with someone at the next table,” says Brown of F.A.R.M. Cafe. “It’s transformative. Rather than having a transactional value at a restaurant, the experience is of having a transformational value. Impacts happen on small levels that are significant.”

Nourishing Community

Open Door Cafe is located in downtown Wytheville, Va. HOPE, Inc., Executive Director Andy Kegley attributes the visibility of the location and the quality of the food as to why the cafe has been so successful over its first year.

Helping Overcome Poverty’s Existence, Inc. (HOPE), a nonprofit organization serving five Southwest Virginia counties, runs Open Door Cafe and has a long history of addressing housing affordability and food insecurity in Southwest Virginia. After the region’s homeless shelter in Wytheville closed in 2012, community members came together to prepare hot meals for 75 people several days a week as a soup kitchen.One day, a HOPE VISTA member told the group about One World Everybody Eats, a nonprofit organization that provides more than 60 existing community cafes in its network with best practices, information and opportunities for networking and mentorship. The organization also helps support startup cafes. F.A.R.M. Cafe, for instance, hosted HOPE in Boone to share their experiences recruiting and managing volunteers and regularly hosts and mentors other cafes, seeking to build community and address food insecurity.

Kegley says, “Our food insecure community is not unlike many other places — around 15 percent of the population in our area is not sure of where their next meal is going to come from.”

Food insecurity limits children and adults’ ability to thrive and can cause health problems such as obesity. Food-insecure children can also face developmental and mental health challenges.

In Johnson City at One Acre Cafe, children eat free, according to Executive Director Michelle Watts.

“We had a family that has a lot of kids,” she says. “They brought their kids in when they had some struggles. Then, when they hit a patch where they had some money, they were able to give back to the cafe. That’s how this place is supposed to work. Helping folks when they are down, and then paying it forward.”Open in July, 2018, Cafe Appalachia in South Charleston, W.Va., operates each weekday and offers catering. Through a community partnership, it hopes to provide 42 jobs through its cafe, catering, food truck and farm over the next three years, according to founder Cheryl Wilson Laws. The program will bring together ReIntegr8, which works with women in recovery, and the Kanawha Institute for Social Research and Action, which works with men on re-entry from prison. The cafe will provide training and support for their clients.

“We are looking to raise our own pork, beef and chicken so that we can be completely sustainable and source local food from within five miles of our location by year three,” says Laws. “The complete operation will be full-circle, down to scraps from the restaurant will go to feed the chickens.”

This holistic approach to rebuild communities is found at all of the pay-what-you-can cafes in the region.

The Food

F.A.R.M. Cafe uses local food when possible, including in their summer “Tomato Pie Tuesday” meals. Photo courtesy F.A.R.M. Cafe

“There is dignity in sharing food with someone and you caring how it’s grown,” says Boughman.

Each month, F.A.R.M. Cafe hosts an all-local lunch from a specific group of farms. The farmers are invited to meet with customers and see how their food is prepared.

“To have the farmers see their work, their love go into a meal that we can enjoy cooking and be a part of, and then to see diners enjoy it — I can’t think of a better way to inspire local folks to want to become involved in local food,” says Boughman.

“We don’t try to be 100% local, we can’t be,” says Brown of F.A.R.M. Cafe. “Where we are able to connect with local food and be a part of the healing, we are. It comes in locally. The compost that we create goes back in locally. We’re about helping the farmers replenish the soil that’s been lost over the years. It’s about this loop on a deeper level.”

In Wytheville, sourcing local food was also an important reason for developing the donation-based cafe model.“We wanted to expand that soup kitchen program into a pay-what-you-can cafe so that we could include healthy, good, local food, because a lot of folks in our area don’t have access to that,” says Kegley.

Like Boughman, Open Door Cafe Chef J.C. Botero comes from a fine dining background and is now able to make locally sourced food like grass-fed beef and hydroponic lettuce accessible to everyone.

“We’re growing our local economy,” says Kegley.

Each of the cafes are still learning and growing to reach a level of financial sustainability and have relied upon grants, fundraisers and grassroots support to start up their operations.

However, several of the cafes are beginning to reach a balance between patrons who are able to donate the full suggested donation and those who donate less. After its first year, Open Door Cafe reports that 35 to 40 percent of its customers donate less than the suggested donation of $8 a meal. In Johnson City at One Acre Cafe, 46 percent have donated more than the suggested donation since December 2013. And in Boone at F.A.R.M. Cafe, 2,637 folks volunteered in 2018 in exchange for meals.

A sustainable financial model is necessary to keep the doors open and the food hot. But at pay-what-you-can cafes, the donations are just a means to an end: a community that is open to everyone.

“Other restaurants are based on money,” says Watts at Open Door Cafe. “These cafes are what community is supposed to be about.”

“We’re not about profit,” says Brown at F.A.R.M. Cafe. “We’re about helping people. The food and the local food is a part of that. What’s broken in our food system is the switch away from knowing the farmer, knowing the community.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment