Living on Bottled Water

NC Community Struggles with Drinking Well Contamination

By Sarah Kellogg

Bottles of water sit in stacks in Amy Brown’s living room. She is now familiar with how many bottles are needed for each family meal — boiling spaghetti takes four, while only two are needed for rice.

Amy Brown is a mother of two raising her children in a small neighborhood of Belmont, N.C., right next to Duke Energy’s G.G. Allen Power Plant. Last spring, her neighbors began receiving letters from the state notifying them that their well water was unsafe to drink or cook with due to unsafe levels of contaminants that can also be found in coal ash. It wasn’t long before Brown received a letter of her own. Prior to the well water tests required by North Carolina’s 2014 Coal Ash Management Act, Brown believed that she was raising her children in a safe, healthy and happy environment.

“Now when I turn on the water,” says Brown, “I turn on fear.”

Drinking water wells in the Belmont neighborhood, like most of the wells tested within 1,000 feet of Duke Energy’s coal ash ponds throughout the state, are contaminated with toxic heavy metals such as hexavalent chromium and vanadium. Hexavalent chromium is a toxic compound, most often formed through industrial processes, that is known to cause cancer. In Belmont, well tests show hexavalent chromium levels ranging from 3.4 times to as much as 71.4 times higher than the state’s allowable standard.

Duke Energy has responded to concerns of residents by providing one gallon of bottled water per person per day. The company refused to answer residents’ questions about the condition of their water, stating only that, “we do not have any reason to believe that the contamination is coming from our coal ash ponds.”

Duke and the state have both tested wells that they claim could not be affected by coal ash in an effort to determine how the high levels of contaminants found in Duke’s neighbors drinking wells compare to other drinking wells in the area. The state tested 24 background wells and published a blog post stating that the levels of vanadium and hexavalent chromium were similar to those nearer to the site. They did not release any data.

In response, Dr. Ken Rudo, North Carolina’s state toxicologist, explained at a community meeting that of the 192 residential wells near Duke’s coal ash ponds tested under the 2014 coal ash law showed unsafe levels of hexavalent chromium, while 74 percent of those wells showed levels higher than the averages found in the 24 background wells tested by the state environmental agency.

In addition, Duke’s groundwater assessment report for the G.G. Allen plant, required by the Coal Ash Management Act and funded by the company, states that the contaminated groundwater coming from Duke’s ash ponds appears to be moving away from neighbors’ wells toward the Catawba River. The study did not include any tests for hexavalent chromium.

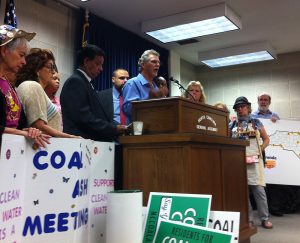

Larry Mathis of Belmont, N.C., represents a new statewide coalition of residents affected by coal ash at a September press conference in Raleigh. Rep. Charles Graham of Lumberton, N.C., sponsored the press conference on behalf of Alliance of Carolinians Together (ACT) Against Coal Ash. Photo by Marie Garlock

Many residents and environmental groups question the validity of Duke’s groundwater report.

Brown questions Duke’s claim that the multi-acred plume of groundwater contamination under Duke’s ponds isn’t affecting her well, which is surrounded on 3 sides by the toxic plume. “That must be some pretty smart water,” quipped Brown, “to know to go right up to Duke’s property line, but never cross it.”

Sam Perkins, the Catawba Riverkeeper, has concerns about the location and depth of both the state’s and Duke’s background wells in addition to the company’s analysis of the groundwater flow.

Despite Duke’s assurance that their study is good news for their neighbors in Belmont, residents with contaminated wells are not reassured.

“We are living off bottled water and our property is worth nothing,” says Belmont resident Larry Mathis, whose well tested 26.8 times higher than the state’s standard for hexavalent chromium. “Duke says they’re a good neighbor, but they need to admit they’ve done wrong and step up to do better. It’s not just our house and our land, it’s our home.”

Brown was consistently disappointed by the lack of answers she received from both Duke and state environmental regulators about the safety of her well water. Since receiving her do-not-drink letter, she has worked to connect her entire neighborhood to the resources they need to receive bottled water and organized community meetings with agencies she hoped would give her and her neighbors answers.

“I am my children’s voice and I have a job to do,” she says. “Trust me when I say that I intend to do it well!”

In late September, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Duke Energy settled a 15-year lawsuit over the company’s violations of the Clean Air Act. Duke was charged with illegally modifying 13 coal-fired units without installing proper pollution controls or obtaining permits. Of those 13 units, 11 have been shut down, but the remaining two are still operating at the G.G. Allen power plant, raising concerns among residents about how the air pollution may have affected their health.

Adding to those concerns is a recent study published by Duke University which found that coal ash particles are ten times more radioactive than the unburned coal it came from. The study noted that inhaling coal ash could be more harmful than previously thought because radioactivity is concentrated in the small particles.

Duke Energy and the state have yet to make any decisions about how to address the coal ash at G.G. Allen, and neighbors are left to wonder what will come of their homes and their lives.

As Brown put it, “How much more of a prisoner can I feel like in my home, when Duke has contaminated my air and my water?”

For the latest on coal ash, visit our Cleaning Up Coal Ash campaign.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment