Alabama Coal: Strip Mine Proposal Halted on Mulberry Fork

The water intake for more than 200,000 residents of Birmingham, Ala., is just across the river from a proposed strip mine — now withdrawn — that would have released toxic pollution directly into the river, including one discharge location a mere 800 feet away. Photos courtesy of Black Warrior Riverkeepers

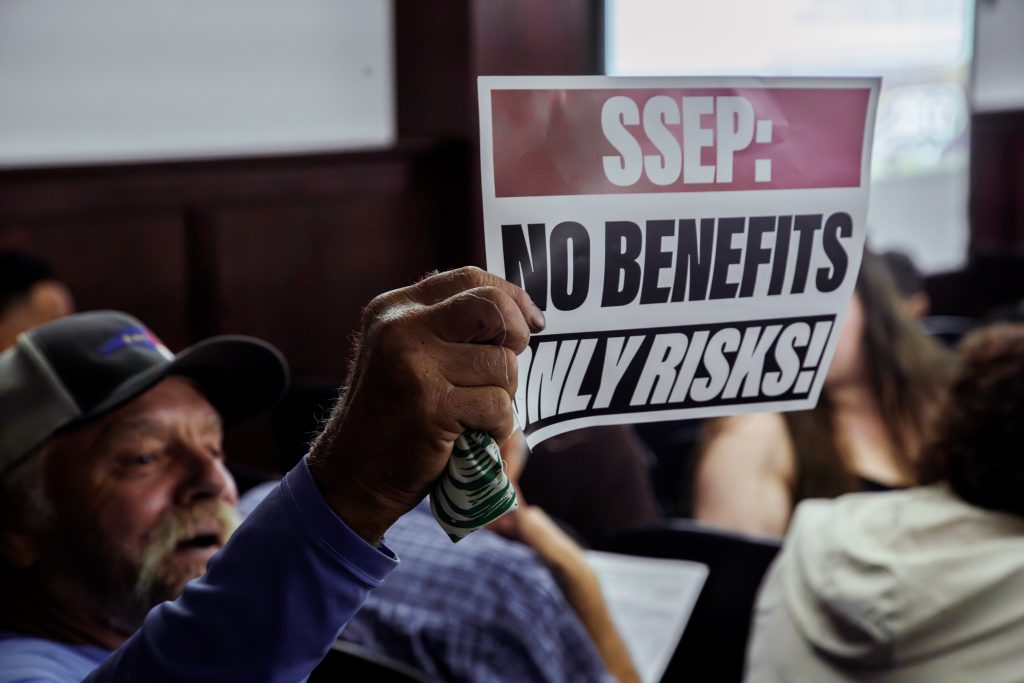

Even to those familiar with Appalachia’s historically destructive relationship with coal, the proposal for the 1,773-acre Shepherd Bend strip mine in northern Alabama seemed unprecedented.

Flowing through the mountains of Alabama’s largest coal-producing region, the Mulberry Fork tributary of the Black Warrior River houses the drinking water intake for more than 200,000 residents in Birmingham, Ala., nearly 75 percent of whom are black or African-American. Just 800 feet from this intake was one of 29 outfall points where Drummond Company, Inc., planned to release toxic mining waste directly into the waterway.

Drummond is no stranger to controversy. Since 2002, the coal mining company has been sued at least four times regarding allegations that it hired the paramilitary gunmen responsible for the kidnap, torture and murder of unionized mine workers and their families at its Colombian operations. But until recently, the company faced limited public criticism in its home state of Alabama.

“The proximity to a major drinking water source was the perfect storm,” explains Black Warrior Riverkeeper Nelson Brooke. “The challenge was getting the word out.”

For the past eight years, Brooke’s organization waged a grassroots campaign against the Shepherd Bend Mine proposal. Confronted with a progressively vocal opposition, Drummond withdrew their permit applications last June. Although the company claims the decision was solely based on a poor market for coal, Brooke suspects that “without this campaign, the mine probably would have gone forward.”

The proposed location for the Shepherd Bend surface mine on the Mulberry Fork. Photo courtesy of Black Warrior Riverkeepers

Alabama has an almost 200-year-old history with coal mining. Along with the rest of Appalachia, however, jobs in the industry began to decline by the 1960s as machines increasingly replaced workers. Yet according to Brooke, there has been “[limited] public awareness just at the fact that there is mining [in Alabama] — strip mining and underground — and a lot of people didn’t realize this was happening here except in immediately affected communities.”

Since the Alabama Department of Environmental Management first granted a wastewater discharge permit for Shepherd’s Bend in 2008, public understanding and opposition has grown. Once Drummond received an additional permit to mine the area in 2010, students from the University of Alabama began to protest.

As owner of most of the property where the mine would have been located, the university had requested proposals to lease the land as recently as 2007. With the negative attention brought on by the protests, the school took no further action after this request expired.

Opposition expanded in 2014 when the story caught the attention of lawyer and activist Natilee McGruder. The disconnect between social and environmental justice movements in her home state of Alabama — particularly in terms of racial demographics — had long troubled McGruder. Joined by her friend William Isom II, co-founder of the direct action campaign known as Hands Off Appalachia!, McGruder encouraged students at nearby historically black colleges and universities to rally around opposition to the Shepherd Bend Mine.

“We started talking about how we wanted more people of color and particularly students, the young folks, engaged [on this issue] and how we thought the students would be a cool way to get this whole idea out that Alabama is Appalachia and Appalachia is Alabama,” says McGruder.

McGruder and Isom visited several schools, hosting workshops and film screenings, and sharing social media and community engagement strategies from central Appalachia. Though the Drummond permit is now withdrawn, Isom’s group is continuing to examine ways to diversify grassroots action in Alabama.

The Black Warrior Riverkeepers remain on guard. The University of Alabama has never stated whether it has future plans to lease its land for mining, and the lax environmental regulations in Alabama which allowed for the Shepherd Bend proposal in the first place are still in effect, although the Riverkeepers and others have initiated several legal challenges.

Isom hopes to see continued crossover between social justice and environmental activism. “The same machine that chews up black men on the streets of America is the same machine that’s chewing up the mountains of Alabama,” he says. “And dumping poison in your water and screwing up your air or making your grandmother have asthma.”

Allure of the Alabama Appalachians

By Eliza Laubach

The Appalachian mountain range extends into northeastern Alabama, with its highest peak, Mount Cheaha, at a 2,407 feet. Attractions include abundant caves, old-growth pines and rare plant communities.

Upper DeSoto Falls. Photo by Kerry Sanders

-

☼ See the nation’s longest flowing mountaintop river at Little River Canyon National Preserve. A spectacular 700-foot gorge, one of the deepest east of the Mississippi, runs for 28 miles atop Lookout Mountain.

☼ The quaint village of Mentone on Lookout Mountain boasts a high concentration of youth summer camps, as well as Alabama’s only ski resort.

☼ Look for the rare carnivorous pitcher plant in DeSoto State Park and boulder the sandstone cliffs near DeSoto Falls.

Green pitcher plant.

Photo by Brad Lackey

☼ Sauta Cave shelters the largest concentration of the Indiana gray bat in the world. Up to 200,000 bats have emerged at dusk in the summer months.

☼ Kayak or raft class three and four rapids in South Sauty Creek, with a take-out at Buck Pocket State Park, and in Short Creek, which empties into Lake Guntersville.

☼ Spot scarce cerulean warblers, whose habitat is threatened by mountaintop removal and strip coal mining, on the northeast loop of the North Alabama Birding Trail.

☼ Stand under 200-year-old longleaf pines at Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge, which protects the largest remaining stand of these pines north of the state’s coastal plains — less than 10 percent of the longleaf pine ecosystem survives. These forests also host an endemic daisy.

☼ The Chief Ladiga Trail is a 33-mile biking trail that was once a railroad bed. Chief Ladiga was a Creek Indian chief who signed a treaty giving most of the land in the area to the United States.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “Alabama Coal: Strip Mine Proposal Halted on Mulberry Fork”

-

Iam looking for information on reclaimed land. My family is looking at purchasing land in Kimberly Alabama that is reclaimed. It backs up to Locust fork /Mulberry -Black Warrior River curious if this is the area the aticle speaks of.

Leave a Comment