Appalachia’s Place in the War on Poverty

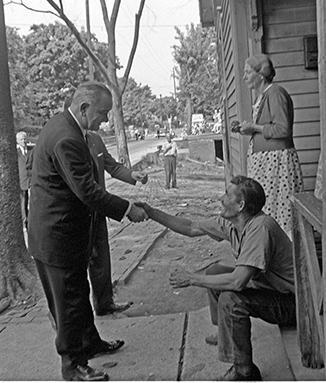

During his official poverty tour in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson shook the hand of a resident in an undisclosed part of Appalachia. Photo courtesy LBJ Library, by Cecil Stoughton

Patsy Dowling considers herself a success of the War on Poverty.

As a premature baby born in western North Carolina in 1964 — the same year President Lyndon B. Johnson declared war on poverty — Dowling entered a world where the medical bills from her early arrival were a steep financial burden for her parents.

Poverty had a profound impact on Dowling’s youth, as did the Economic Opportunity Act that Johnson signed in 1964. On Valentine’s Day, a second-grade Dowling learned that one of her dearest friends had passed away from illness because her family couldn’t pay for care. She recalls standing beside her friend’s coffin more vividly than she remembers her high school prom dress. Yet she also clearly remembers her excitement when an outreach worker from Mountain Projects, Inc., one of the new community action agencies created to fight poverty, visited her home and offered her a seat in Head Start, an early childhood school-readiness program she saw as “the best thing in the world.”

Dowling, now executive director of Mountain Projects, estimates that about 90 percent of her Head Start classmates were able to overcome their families’ financial difficulties. Today, Head Start remains at the core of the agency, but other top priorities include heating assistance for struggling families and transportation for the elderly. “We still have a lot of work to do, but I do think the War on Poverty has made a substantial impact in this country from my perspective of having lived it,” Dowling says.

National and regional data support her view that the policies set in motion in the mid-1960s — such as Medicare and Medicaid, food stamps and Head Start — have helped avert dire economic circumstances for much of the population. When researchers from Columbia University examined the impact of government benefits such as housing assistance and tax credits during the period from 1967 to 2011, they found that the 16 percent national poverty rate in 2011 would have been equivalent to 29 percent without those benefits. Yet, as the nation grapples with growing income inequality and the slow recovery from the Great Recession of 2009, it’s clear that the War on Poverty is not over.

Charting Appalachian Poverty

Ever since President Johnson declared “unconditional war on poverty in America,” Appalachia has held special significance in the national effort. In 1964, when the president embarked on a publicity tour to build support for the new programs, he led national media to eastern Kentucky, where he was famously photographed speaking with a poor Appalachian family on their front porch.

The official definition of Appalachia also formed in the early 1960s, as regional governors encouraged the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to assist their mountain counties, where one in three residents lived in poverty. The resulting legislation, the Appalachian Regional Development Act, added a unique, place-based dimension to the War on Poverty’s suite of national programs.

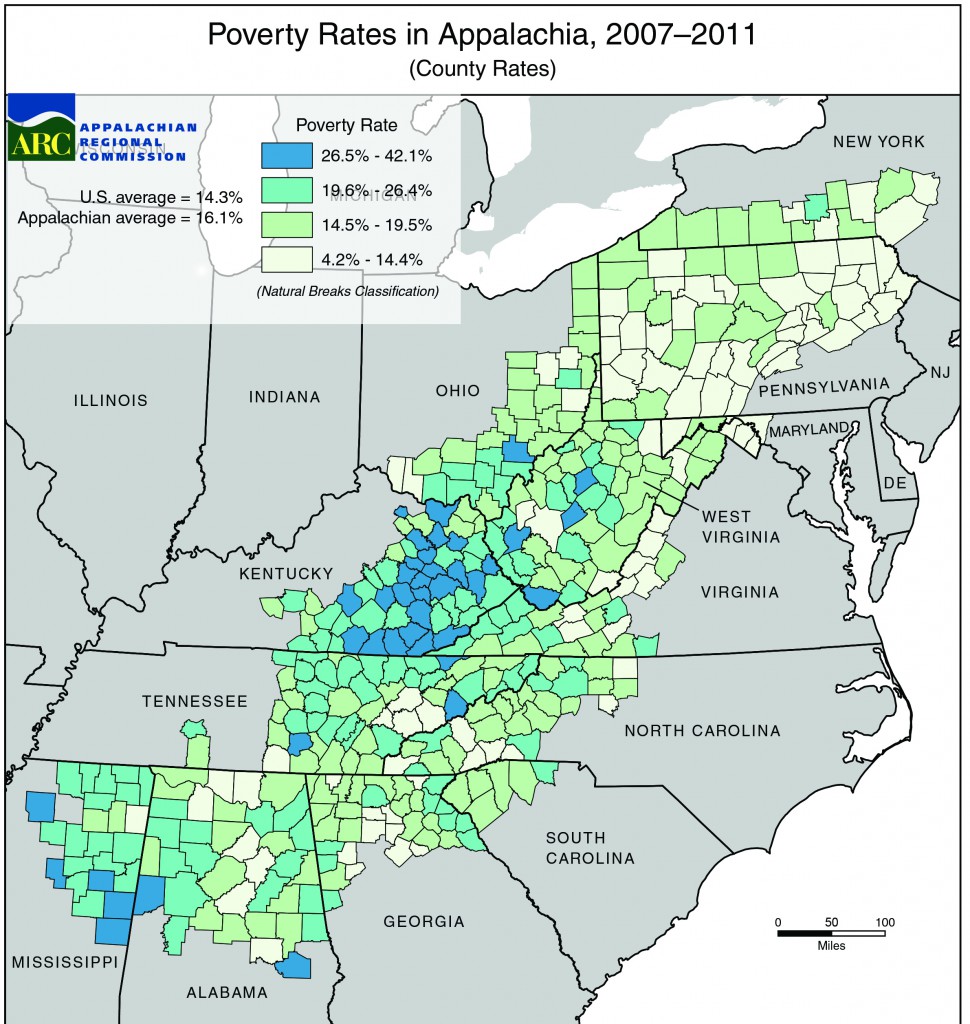

Fifty years later, however, central Appalachia is still a national epicenter of poverty, sharing the distinction with the Mississippi Delta and several western Native American regions. And while data from both Appalachia and the nation at large shows an overall reduction in poverty, deep inequity persists within the region.

From the outset, central Appalachia faced the steepest challenge. Dr. James Ziliak, director of the University of Kentucky’s Center for Poverty Research, calculated poverty rates both nationally and within Appalachia in 1960 and 2000. Faced with a poverty rate of 59.4 percent in 1960, central Appalachia was far more impoverished than its northern neighbors, with southern Appalachian states a close second. By 2000, the poverty rate in the southern and northern areas was slightly above the rest of the country’s average of 13.4 percent. Yet poverty in central Appalachia stayed stubbornly high at nearly 23 percent.

Ziliak attributes this partially to the fact that federal aid originally intended to address the deep poverty in the mountains of Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia was ultimately dispersed over a larger area. Between 1965 and 2008, the official Appalachian zone expanded from 360 counties in 11 states to its present size — 420 counties in 13 states.

In the decades after the War on Poverty began, northern and southern Appalachia fared better than the central states. Map created March 2013; Data source: US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2007-2011

Proponents of the Appalachian Regional Development Act, passed in 1965, argued that the country had exploited the deeply impoverished parts of Appalachia through decades of coal and timber extraction and that the region deserved compensation. The law created the Appalachian Regional Commission to invest in areas such as education, job training and transportation infrastructure. Still, Ziliak notes, “the money flowed more toward the urban areas in the region and not toward the really high-need rural parts that many governors and policymakers in the Appalachian region really wanted.”

Ziliak adds that the appetite for funding the ARC decreased after the first five years, weakening the federal commitment to the region. “So, while the War on Poverty did have a positive effect on the region, coupled with the Appalachian Commission, presumably the effect would have been stronger still had the investment been more focused,” he says.

Roads, Sewers and Jobs

The architects of both the War on Poverty and Appalachian Regional Commission believed in investing in infrastructure as well as people. Many of the ARC’s most high-profile projects were the construction of roads, bridges and dams.

These policies also spurred projects that were less visible but still valuable. In the mid-1960s, outreach workers from one of the War on Poverty’s community action agencies — a Roanoke, Va.-based organization now known as Total Action for Progress — surveyed low-income residents in the surrounding rural areas to identify pressing needs. Access to safe drinking water was a paramount problem. In response, the community agency designed a program to help residents develop and finance community water systems.

The successful Virginia program caught the attention of federal policymakers and became national in the 1970s. But the connection between poverty and underperforming water utilities endures. Today, many low-income areas face mounting needs for investment in town sewers. Hope Cupit, CEO of the southeastern program, says that while many older water systems are due for expensive repairs, a number of rural communities have seen their populations drop. As a result, there are fewer community tax dollars to finance the needed upgrades.

Though government agencies are still making specific investments in the region’s hardware, such as installing broadband internet cable, programs that focus on individual needs are becoming more of a priority. Tony Wilder, commissioner of the Kentucky Department for Local Government, also serves as the liaison between the Kentucky governor’s office and the Appalachian Regional Commission. He says the ARC and states like Kentucky are shifting their attention to what policymakers call “human capital.”

With several eastern Kentucky counties suffering from prolonged double-digit unemployment, the focus has shifted to education and job training. “I feel the main role of ARC resources is to diversify the economy and create some new jobs and keep those folks in eastern Kentucky if we can,” Wilder says.

The current spotlight on employment represents more of a shift than a wholly new approach. Ziliak estimates that since its inception, the ARC has devoted about half of its investments to people-focused projects such as community health and job training centers. He says that when the impact of other War on Poverty programs such as food stamps and Medicaid are factored in, more was spent on people than infrastructure.

Taking Community Action

In the Roanoke Valley, the community action agency Total Action for Progress, Inc., takes a multi-pronged approach to the fight against poverty, in some cases building homes and job skills in the same breath. Through a partnership with Habitat for Humanity to construct and renovate affordable homes, TAP’s YouthBuild program helps students who have dropped out of school earn a GED, work experience, and a pre-apprenticeship certification in green construction. Other TAP endeavors range from providing adult literacy classes and support for victims of domestic violence to job-placement services for veterans and weatherization of low-income homes.

As with many community action agencies, TAP began by offering Head Start. The organization served 100 Head Start students in 1965; today, TAP serves 9,000 residents. Annette Lewis, a TAP director who has been with the organization for 25 years, says services such as the re-entry program for young offenders are in keeping with the community action agency’s original goal: providing a “hand-up” to those in need.

In Virginia, students learn about construction safety through YouthBuild, a program provided by the local community action agency. Photo courtesy Total Action for Progress, Inc.

Lewis describes the idea of winning a war on poverty as being very ambitious, noting that environmental, health and infrastructure problems all play a role in an individual’s economic circumstance. “I don’t think we can win a war on poverty unless everybody is committed to doing that, every system, not just community action,” she says. “Because life happens, you’re going to have poor people. And some are going to be poor because of mistakes they’ve made and some are going to be poor just because of the hand they’ve been given.”

Across the country, community action agencies such as TAP and Mountain Projects are seeking creative funding sources to make up the difference lost by federal and state budget cuts. TAP is pursuing special tax credits to help fund affordable housing development and small-business loans, and this winter Mountain Projects partnered with a local credit union and other organizations for a “Million Coin Campaign” to help offset the burden of high heating bills for those in need.

“I have a strong philosophy from my life and my experiences that if you go into any Head Start classroom in this country or any public school and you ask a child what they want to be when they grow up, they don’t say poor,” says Patsy Dowling. “Those children have hopes and dreams and somewhere along the way those don’t come to fruition. And so we have to constantly look at how can we help them meet those hopes and dreams.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *