Mountaintop Removal Masquerade

Opponents of Proposed Surface Mine Highway Push for Environmental Review

By Molly Moore

Citizens opposed to the Coalfields Expressway rally outside the Federal Highways Administration offices in Washington, D.C. in December. Photo courtesy of Sierra Club.

Tim Mullins recalls what Pound, Va., was like in the 1970s — nestled in the commonwealth’s mountainous southwestern corner, it was a town of crowded sidewalks, ample schools and nary a parking spot to be found. Today, formerly bustling businesses are dilapidated eyesores, trees are sprouting on the sidewalks and the schools are closed.

Pound’s downturn troubles Mullins, a southwest Virginia native who cares deeply about his community. Yet he is adamantly opposed to the Coalfields Expressway, a proposed highway that coal companies and state proponents tout as a solution to the area’s lagging economy. For Mullins, the current road plan is a mountaintop removal coal mine in disguise that holds scant economic potential and great environmental peril.

The project was conceived in 1995 as part of a 116-mile, four-lane interstate to connect Pound, Va., and Beckley, W.Va. But the commonwealth determined that the roughly $5 billion project was too expensive and placed the Coalfields Expressway on the backburner.

In 2006, following West Virginia’s example, two coal companies — Alpha Natural Resources and Pioneer Group — offered to nearly halve Virginia’s construction cost by surface mining a 50-mile section of the route and leaving behind a rough-grade road bed. By creating a “coal synergy” public-private partnership, a new route was proposed, which follows coal seams to maximize coal extraction but skirts local economic hubs near Pound such as Grundy and Clintwood.

“This new route that they’ve made, it’s going to just bypass all these little towns,” Mullins says. “It just doesn’t make any sense to me because it’s just going to make less jobs for people and it’s just going to do more damage to our water and our health.”

The original proposal, which was subject to a federally required environmental impact statement in 2001, would have destroyed 720 acres of forest and four miles of streams. In comparison, more than 2,000 acres of forest and twelve miles of streams are slated for demolition with the “coal synergy” route, yet no thorough study of the new plan’s environmental impacts has been conducted. Instead, in 2012 the state completed a draft of a more cursory environmental assessment, which doesn’t address the effects of mining or analyze how the new route will affect local economies.

During the past year, opponents — including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of The Appalachian Voice — collected roughly 90,000 public comments and petition signatures asking the Federal Highway Administration to require the state of Virginia to complete a full supplemental environmental impact statement that reflects the route changes.

“We think that if you did a full analysis you would find that there’s greater cost, and that the impacts from the mining would be against the law — disposing pollutants into already-impaired streams,” says Sierra Club organizer Marley Green, who lives in Wise County, Va. “We feel the impacts of the mining proposed by this route are a violation of the Clean Water Act.”

According to Green, an environmental impact statement should also consider how the road would affect the health of nearby communities in light of recent studies that connect health problems to surface mining.

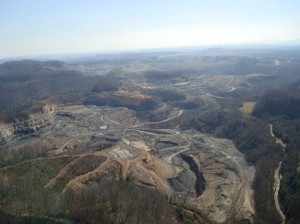

An aerial image from the Virginia Department of Transportation shows progress on the Hawks Nest portion of the highway.

Mullins, who serves as a volunteer and board member with The Health Wagon, a nonprofit that provides healthcare to underserved populations in six southwest Virginia counties, surveyed mountain residents about their health concerns. He estimates that 75 percent of those he spoke with don’t trust local water quality. “How do you keep someone from getting cancer who lives along one of these creeks and rivers that has got arsenic in it?” Mullins asks.

Adding to the environmental risk is a legal provision known as the Government Finance Exemption, which would excuse the participating coal companies from complying with federal surface mining reclamation laws.

Jane Branham, vice president of local organization Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards, forecasts a grim worst-case scenario. “It’s going to be left to the taxpayers to reclaim, under the guise of a highway, which the state of Virginia is not equipped to fund,” she says. “And the people living there will be just about run out of their homes. If you’ve never lived or been near a mountaintop removal site it’s not a pretty thing. It’s very devastating, it’s constant coal trucks, machines, blasting, dust — it’s not just what you see, it’s everything in the air, in the water. It’s a scary thing.”

Branham warns that by diverting traffic away from small towns, the highway will stymie efforts to boost tourism.

“I see the people around me and other citizens trying to work to create something new because they want to live here and survive as a community, and I don’t see any help from [our politicians],” she says. “It’s very disappointing, but it comes back down to [the fact that] it’s people that make things happen anyway, and then politicians somehow manage to take the credit for it.”

“I think that it’s time to invest back in Appalachia and [the Coalfields Expressway] is not it,” Branham continues. “Another strip job under the guise of a road is not it.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment