A Finite Frontier: Facing the Future of Central Appalachian Coal

By Brian Sewell

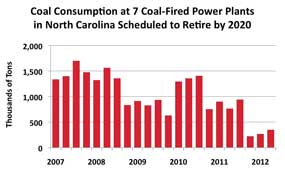

The decline in demand for coal influenced a decision by Alpha Natural Resources to restructure operations, and reduce production of coal sold to electric utilities in the U.S. In North Carolina, the largest consumer of Central Appalachian coal, consumption at seven plants scheduled to retire before 2020 has fallen by 80 percent in the past five years. Data compiled by Appalachian Voices

On Sept.18, Appalachian coal mining giant Alpha Natural Resources announced it would idle eight mines and lay off 400 employees in the first phase of a “strategic repositioning” plan designed to meet the evolving demands of a changing global coal market.

According to Alpha, the plan aims to enhance the company’s position as the nation’s leading producer of high-quality metallurgical coal used to make steel, while reducing production of lower-quality thermal coal sold primarily to electric utilities in the United States.

A statement from Alpha on the day of its big announcement said that “approximately 40 percent of the reduction will come from higher-cost thermal coal operations in the East that are unlikely to be competitive for the foreseeable future.”

Although Alpha did not comment on why some thermal coal mines are no longer competitive, political figures in Appalachia were quick to blame regulations designed to reduce pollution from mines and power plants that burn coal.

West Virginia Rep. Shelley Moore Capito wrote in a response to Alpha’s announcement that, “Because of the President’s War on Coal, thousands of West Virginia families have to worry about where their next paycheck is going to come from.”

Reports from the Energy Information Administration and private consulting firms, however, suggest that environmental regulations play only a minor role in the planned retirements of 10 to 20 percent of the nation’s coal-fired power plants. Instead, analysts say, a surge in the production of low-cost natural gas is forcing coal out of the market.

In 2011, North Carolina purchased 95 percent of its coal from West Virginia, Kentucky and Virginia coal mines. Yet, even utilities in the Tarheel State, the largest buyer of Central Appalachian coal, have laid out plans to retire more than a quarter of their coal-fired generating capacity, replacing much of it with natural gas-fired units.

Just days before Alpha announced its repositioning, North Carolina-based Progress Energy shuttered its H.F. Lee Plant, a 385-megawatt facility near Goldsboro almost a year earlier than it had initially intended to begin construction on a natural gas facility at the site. The second in a string of closures Progress calls its “fleet-modernization” initiative, the Lee plant has relied on Central Appalachian coal since it was built in 1951. Next year, Progress will retire the L.V. Sutton Station in Wilmington, which has been in operation since 1954, and replace it with a 625-megawatt gas-fired power plant.

“We’re closing one chapter, but opening another,” Jeff Lyash, vice president of energy supply for Duke Energy, which recently merged with Progress, told the investment analysis website, SeekingAlpha.com. In June, Duke CEO Jim Rogers said the utility now relies on its coal fleet only when hydroelectricity, nuclear and natural gas do not meet demand.

Exacerbating the competition from natural gas in domestic markets, mining conditions have deteriorated dramatically in recent years due to the depletion of the highest quality and most accessible seams of coal. In 2008, the EIA reported that West Virginia produced 157.8 million tons of coal. It predicts that number could drop to 90.1 million tons per year by 2020, a decrease of more than 42 percent.

Until recently, however, coal mining employment has remained stable or grown in some parts of Appalachia. Counterintuitive to the logic of the “war on coal,” EIA data compiled by the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy suggests that as productivity of mines decreases due to less accessible coal seams, it may mean a boost in employment in the long-term.

The center also noted that the type of coal being mined is changing. One of the key components of Alpha’s restructuring is shifting the focus to metallurgical coal for steelmaking in nations such as China where demand continues to grow. That may translate to more jobs in underground mines where high-quality and high-cost metallurgical coal is found. Despite plummeting productivity, one estimate suggests there may be 10,000 more coal jobs in Central Appalachia in 2035 than in 2010.

“We really don’t know how it will all shake out,” said Sean O’Leary, a policy analyst at the budget and policy center. “The mix of falling production and falling productivity may eventually increase jobs, but even in that case it takes years for the initial losses to come back.”

In the meantime, the center advocates for the formation of a coal mining transition taskforce that will “help communities look for viable ways to ease the possible impact and search for viable economic alternatives,” and is calling on West Virginia and all of the coal mining states in Appalachia to invest in what the future holds for coal miners — not just the coal mined.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment