Front Porch Blog

By Brian Sewell

Cost overruns and construction delays are dampening enthusiasm for carbon capture and storage technologies

A rendering of FutureGen 2.0. Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Energy pulled its funding from the project, which was intended to demonstrate the feasibility of carbon capture and storage technology on a commercial-scale. Credit Department of Energy.

As one of the most high-profile and hyped-up projects of its kind, the FutureGen “clean coal” plant in Illinois was supposed make history. Its backers saw in it the key to unlocking an inherently dirty energy source’s promise in a world coming to grips with climate change.

So the announcement earlier this month that the U.S. Department of Energy is backing out of its $1.1 billion funding commitment to the FutureGen project, citing a desire to “protect taxpayer interests,” sent a shockwave through the coal sector and investors, energy analysts and environmentalists all took note.

But the news that “clean coal” technology has taken yet another hit should not come as a surprise. Even with $6 billion in commitments under the Obama administration, carbon capture projects just don’t have the track record needed to pique private investors’ interest.

Every form of carbon capture technology comes with technical and technological drawbacks that translate to enormous costs. A commercial-scale “clean coal” plant using even the most advanced technologies may increase the cost of electricity by up to 80 percent, according to DOE. These challenges make commercial-scale carbon capture projects outcasts when it comes to competitive energy markets, where traditional fossil fuel plants and, increasingly, large-scale and distributed renewable projects represent the most cost-effective power sources.

Convinced that coal will remain one of the nation’s foremost energy sources for decades to come, DOE will put billions more into advancing “clean coal” technology, attempting to overcome its economic pitfalls and keep burning the dirtiest fuel around.

FutureGen’s Downfall

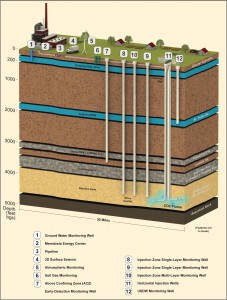

FutureGen 2.0 planned to transport CO2 waste approximately 30 miles through pipelines before being injected in deep saline formations. Click to enlarge.

The idea for FutureGen arose in 2003 under the Bush administration. The plan was for the FutureGen Industrial Alliance, a coalition of mining and energy companies including Alpha Natural Resources and Peabody Energy, to oversee retrofits to an existing coal plant and, in the process, prove the feasibility of burning coal, then capturing and storing the carbon emitted underground.

But the project soon began suffering from the delays, cost overruns and other challenges that will be its legacy. FutureGen was canceled, for the first time, in 2008 before construction could begin.

In 2010, the Obama administration used stimulus money to give FutureGen new life as FutureGen 2.0, a smaller proposed plant that would use a different technology to capture its emissions, but still show how carbon capture could make a more climate-friendly coal plant. For a time, everything seemed to be going in FutureGen’s favor. But then familiar cracks started to appear.

The Illinois Commerce Commission approved a controversial plan in 2012 to require utilities, and therefore their customers, to buy all the electricity generated by the FutureGen plant for 20 years — likely at dramatically over-market rates. The decision may have reassured some private investors, but challenges to the decision by the utilities themselves were headed to the Illinois Supreme Court.

The Sierra Club challenged the air pollution permit granted to FutureGen by the Illinois Pollution Control Board, saying the State of Illinois should hold FutureGen to its promise to build a “near-zero emissions” plant. FutureGen needed to convert a World War II-era boiler at the plant to one compatible with the oxy-combustion technology it planned use to capture its emissions. The Sierra Club argued that allowing FutureGen to convert the boiler would violate the federal Clean Air Act unless it obtained the appropriate permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

All of this is to say that the DOE isn’t entirely, or even mostly, responsible for FutureGen’s failure. Unresolved legal battles, environmental and economic concerns all combined to hurt the chances of attracting enough private investment to bring the $1.65 billion project online. It became clear that the project could not be completed by September 2015, the deadline for federal funds to be spent under the 2009 stimulus, so DOE pulled the plug.

According to DOE, approximately $116.5 million of the total award had been invested in the plant since 2010.

The Sierra Club, which has called FutureGen a boondoggle from the very beginning, said the news reflects a national trend toward embracing clean energy.

“This project has gone through a decade of false starts and with today’s announcement, $1 billion in federal funding and hundreds of thousands of dollars in Illinois ratepayer financing can be freed up for investment in clean energy,” Holly Bender, Deputy Director of the Sierra Club Beyond Coal campaign, said in a statement.

Coal industry groups directed their frustrations toward the Obama administration and mostly overlooked the host of other challenges facing FutureGen.

Hal Quinn, president of the National Mining Association, said in a statement that DOE’s decision to end funding for FutureGen “cannot be reconciled with the [Obama] administration’s proposal to require CCS as the only acceptable technology for any new coal-fueled power plant in the U.S.”

Proceed with Caution

A “first-of-its-kind” technologically speaking and the most expensive coal plant of all time, Mississippi Power’s Kemper Plant has put ratepayers at risk in pursuit of unproven and far-off returns. Photo from Wikipedia.

Carbon capture is a must if future U.S. coal plants — if there is such a thing — hope to meet regulations on greenhouse gases being developed under the Clean Air Act.

Analysts say the only way to create a market for carbon capture technology, at least one that would attract significant private capital, is by capping power plant pollution. But groups like the National Mining Association lambast the president and the U.S Environmental Protection Agency for pursuing policies that will limit carbon pollution from power plants and steer investments toward alternative forms of energy, including “clean coal.”

Even with a strong climate policy, some experts doubt commercial-scale “clean coal” projects will be around in time to make a meaningful contribution to reducing carbon pollution. Sean Casten, the president and CEO of Recycled Energy Development, recently drew the comparison between the likelihood of the technology’s success and the existence of unicorns.

“I suppose it’s possible that there will suddenly be a huge pot of capital willing to invest billions of dollars in an unproven technology with long construction times and regulatory-dependent cash flows,” Casten told SNL Energy. “But unicorns are more likely.”

Another notable casualty is Tenaska’s $3.5-billion Taylorsville, Ill., plant, which the Nebraska-based energy developer canceled in 2013. The company cited market conditions that led it to focus on developing natural gas and renewable energy facilities instead. But the fact that Illinois lawmakers would not agree to a 30-year contract to buy electricity from the plant, and pass those high costs on to ratepayers, had something to do with it.

With the Taylorsville plant and FutureGen off the table, the U.S. is left with one utility-scale carbon capture project currently under construction. But Mississippi Power’s Kemper Plant, which received a $270 million grant from DOE, is like the projects before it: more of a cautionary tale than a positive sign for coal’s future.

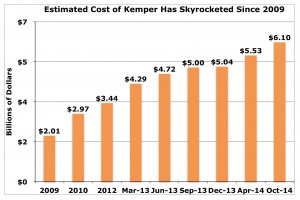

Cost increases have been like clockwork at Kemper. Initially estimated to cost $2.2 billion, the price to build the plant has ballooned to $6.17 billion since 2009, making it the most expensive coal plant in U.S. history. Southern Company, the parent company of Mississippi Power, announced a $45 million increase this month.

$6 billion and counting: Cost increases at the Kemper Plant have been like clockwork since 2009. Graphic by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

To help pay the bill, the Mississippi Public Utilities Commission approved an 18 percent rate hike on Mississippi Power in March 2013, and the company says it’s likely to seek another increase of at least 4 percent to help pay off $1 billion in bonds that the state legislature is allowing it to issue.

“This is the largest rate increase in the state of Mississippi’s history, and this is the largest transfer of wealth from the people to a corporation in the state of Mississippi’s history,” Public Service Commissioner Brandon Presley told Mississippi Watchdog in 2013.

Presley was the only dissenting vote when the commission approved the rate increase. But now the state’s highest court is on his side. Last week, the Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the rate increase after finding the utilities commission hadn’t ruled on the “prudency” of the Kemper Plant’s growing cost. The court directed Mississippi Power to refund ratepayers about $271 million attributed to the rate increase.

The Kemper plant is slated to open in mid-2016, more than two years behind schedule.

The quest to create a cleaner future for coal increasingly rests on the question of how much we’re willing pay for it.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *