Mine Cleanup Concerns Grow As Industry Declines

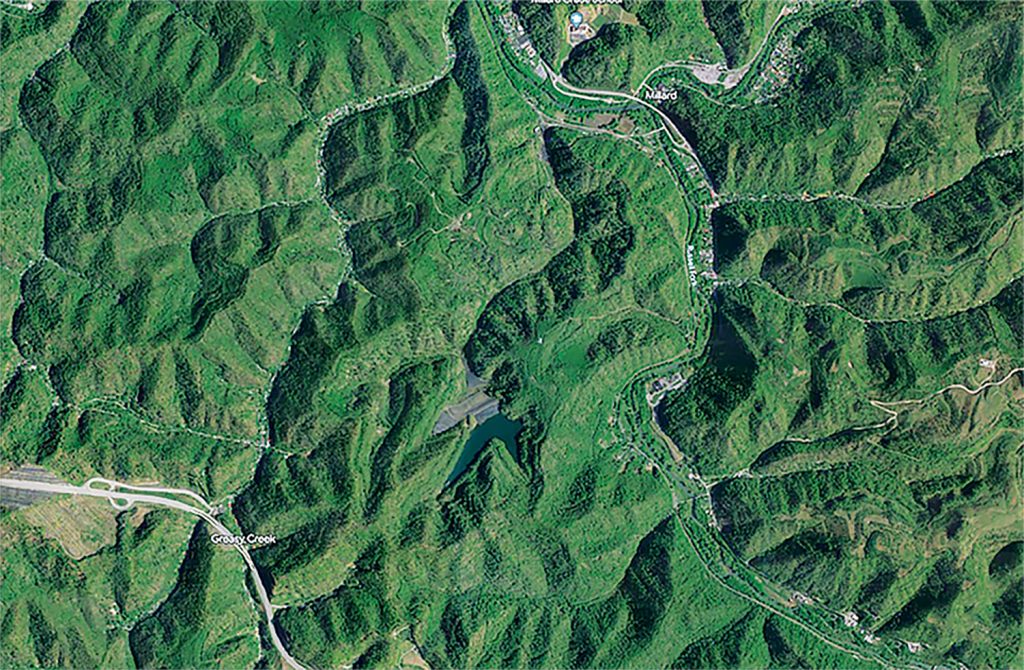

This Google Earth satellite image of the Hopkins Creek coal slurry impoundment in Pike County, Kentucky, shows gullies along the side of the earthen dam.

By Dan Radmacher

Since Blackjewel LLC and its affiliates filed for bankruptcy in July 2019, there has not been a coal company bankruptcy of similar magnitude. But that doesn’t mean the coal industry is recovering.

A June 2023 report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that coal production would decline by 6% in 2023 and by an additional 14% in 2024, reversing gains made in 2021 and 2022 during the pandemic.

Erin Savage, senior program manager for Appalachian Voices, the organization that publishes The Appalachian Voice, looked at Central Appalachian coal production and found that it declined 44% from 2018 to 2022. Energy Information Administration anticipates steeper declines for Appalachian coal production in 2023 and 2024 than the national average.

“Recent production data from Central Appalachian mines and forward-looking projections from the EIA confirm what many in the region have been saying for years now — that coal production is on a steady and permanent decline,” Savage says. “Given this reality, it is imperative that coal companies and regulatory agencies make sure that sufficient resources are available to complete mine reclamation in the near future. This will not only keep coal miners at their jobs longer, but will also help coal-bearing regions be best prepared for economic transition.”

Reclamation is the process of fixing land damaged by surface mining. This includes getting rid of dangerous highwalls, revegetating the land, and taking other steps to restore the site, minimize the pollution it generates, and prevent hazards like landslides and retention pond failures.

A System on the Brink of Collapse

Cleaning up mines is expensive. A system set up by the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act intended to ensure that coal companies have the resources to clean up their own mess — and that they clean up as they go. In both cases, the system is failing, and the decline of the coal industry is only exacerbating those failures.

“There’s a huge lag between when coal is removed from a mine and when the reclamation actually happens,” says Mary Cromer, deputy director of Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, a Kentucky-based organization. “That’s not the way the regulations are written. That’s not the way the law is written. That’s not the way it’s supposed to happen. Regulators need to make sure that coal companies are reclaiming as they are mining and that they’re doing a good job.”

The law includes a requirement for what’s called “contemporaneous reclamation” — restoring the land as soon as feasible after the coal is mined. If coal companies don’t keep up with reclamation on sites as they mine, there will be a bigger mess to clean up if those companies use bankruptcy to walk away from their obligations.

“The overall trend is that mines are going to continue to close,” Cromer says. “There’s just not going to be as much production. That continues to stress the reclamation bonding system and calls into question whether some of these mines, especially surface mines, will be able to get reclaimed in a timely fashion, as well as who will ultimately be responsible for reclaiming them.”

Under the 1977 mining law, coal companies are required to post bonds to cover the cost of cleaning up mines if they go bankrupt. These bonds can take a number of forms and include cash collateral, insurance-backed bonds and collective bond pools, among others.

The common denominator among all these different bonding systems: The amount collected is often woefully inadequate to actually get the job of cleaning up the mines done. In addition, many of the funding schemes for mine cleanup depend on fees from new mines coming into the system. As coal production falls, those fees are not coming in.

“The bonding system needs to be strengthened to ensure that there is sufficient bonding for each mine,” Cromer says.

Regulators need to increase bonding requirements, better enforce contemporaneous reclamation standards and take other steps to prepare the system for additional coal company bankruptcies, according to Cromer.

“All that needs to be done, but it’s clear it won’t be enough, and it won’t happen in time,” she says.

Available bonds would cover only between 39% and 51% of coal companies’ existing reclamation liability across eight Eastern states, a 2021 study by Savage found.

Homes and roads lie downstream from the Hopkins Creek coal slurry impoundment in Pike County, Kentucky. Federal and state regulators have issued violations against the current permittee, which is the seventh operator of the site.

Communities at Risk

This situation can leave taxpayers on the hook to clean up coal companies’ messes — and communities at risk from the dangers of unreclaimed mine land.

“There are communities throughout Central Appalachia that are directly below these mine sites, especially mountaintop removal sites,” Cromer says. “These communities experience a higher risk of landslides and of flooding caused by instability at these sites. They are also experiencing pollution from water emanating from these sites. There’s real uncertainty about who will step up and protect these communities from the dangers these sites leave behind.”

Larry Thacker lives in Pike County, Kentucky, below the John Bevins Branch mine owned by bankrupt Cambrian Coal. When John Bevins Branch was active, Thacker dealt with dust, noise and blasting damage — along with a flood and torrent of rock that filled his stream when a silt retention dam failed.

Other residents in nearby hollows had it worse, with fly rock shot off the mine by blasting. One boulder took a house off its foundation, according to Thacker.

When Cambrian declared bankruptcy, Thacker started sending letters to the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet pointing out the problems on Cambrian’s sites. He also brought up a huge coal waste holding pond at Hopkins Creek that has him very concerned.

Pristine Energy, the company that is trying to buy Hopkins Creek, is connected to Myra Coal, the company trying to buy the Cambrian mines, according to the Cambrian bankruptcy documents. Pristine, though, has not secured transfer of the permits, which was supposed to be undertaken by its designees like Myra Coal.

“The problem is the permits for those operations haven’t transferred yet,” says Matt Hepler, Central Appalachian environmental scientist for Appalachian Voices. “That raises questions about liabilities because the owners aren’t the permittees. Meanwhile, these mines are racking up violations.”

“It’s a 30-acre pond, 450 to 500 feet above the valley floor,” Thacker says. “It’s one of the most dangerous ponds in Eastern Kentucky. If that thing ever breaks … we all remember what happened at Buffalo Creek. Even if there is no loss of life, just tons and tons and tons of that coal waste will hit the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy River.”

The impoundment will be the subject of an administrative law hearing in August 2023 for unresolved violations. Thacker has zoomed in on Google Earth images of the dam that show massive cracks on the valley side.

A January 2023 inspection by the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement noted several ongoing violations, including gullies and vegetation on the impoundment and a violation for failing to conduct an annual assessment of the impoundment’s structural integrity.

“All I see is that the damage that was done won’t be cleaned up,” he says. “The Best-case scenario would be someone with the money to come in and finish the job and then fix it up.”

But he says what’s more likely is an underfunded company will try to take over the permit and get any easy coal that’s left — and then leave all the mess behind.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment