How a Pipeline Battle Led an Advocate for Formerly Incarcerated People Into Solar Workforce Development

By Dan Radmacher

It’s been a long route from convicted felon to returning citizen to civil rights activist to anti-pipeline crusader to green-energy proponent and workforce developer. But each step since he returned from prison after serving his time appears motivated by the same thing: Richard Walker’s drive to right wrongs.

“I returned back to Richmond and found out my civil rights had been taken from me and that made me kind of angry,” Walker says. “My family instilled in us, because of what they had gone through to get the right to vote, that we had to vote. I voted in every local, state and national election since I was 18. … So when I realized that in Virginia, you lose that right, that’s when I became an advocate for change.”

Gov. Bob McDonnell restored Walker’s right to vote in 2012, and since then, Walker figures he’s helped about 10,000 other returning citizens regain their right to vote.

In 2009, he started Bridging the Gap in Virginia, a nonprofit devoted to helping the formerly incarcerated get their rights back and to helping them and other at-risk individuals find employment and overcome barriers preventing their success.

Members of the June solar job training session work on an installation project at the Sankofa Community Orchard in Richmond. From left to right: Instructor Duane Cunningham, Rozwell Dionavan Ramseur, Macio Hill and Quaadir Berry (with Richard Walker seated in the background). Photo by Mason Manley.

Walker has worked with gubernatorial commissions on prison and criminal justice reforms, and helped lead a “ban the box” campaign to prohibit employers from asking about arrests and convictions until later in the hiring process.

Then, in 2018, he received a call from a cousin in New Jersey warning him that the family farm in Buckingham County was under threat from the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Developers wanted to put a compressor station for the pipeline right by their land — land his great-grandfather had purchased from the person who had enslaved him.

“Dominion thought they could come into a historical African-American community and just do what they wanted to do,” Walker says.

As a child, Walker spent his summers in Buckingham County, getting up at 5 a.m. to milk cows, feed chickens, slop hogs and walk cows out to the pasture.

“They lived off the land,” he says of his family. “My uncle would kill a hog and put it on a spit for the family reunions.”

Those reunions were huge. Walker’s grandmother was one of 13 children. “That’s when Buckingham was rich in family,” he says. “ACP caused a major division in those families in Union Hill.”

Some people supported the pipeline, believing the compressor station would bring jobs and money. “Some folk wanted the money because they were living day-to-day on fixed income,” Walker says.

Walker got heavily involved in the fight against the compressor station and the ACP, and celebrated when the pipeline was canceled, but he says some family members still aren’t talking to each other because of their differences.

In an attempt to heal the rift in the wake of the pipeline cancellation, Walker brought Bridging the Gap to Union Hill and worked to educate the community about greenhouse gas emissions, climate change and renewable energy. Walker decided to add environmental justice and workforce development to Bridging the Gap’s mission.

A grant from the Mertz-Gilmore Foundation funded the first solar job training session, held at Union Grove Missionary Baptist Church in June 2019. Ten students took the week-long training. After that, the foundation offered to fund additional training sessions in Richmond.

Mertz-Gilmore is not the only benefactor. Bridging the Gap also partners with the Richmond Office of Community Wealth Building, and the city’s Parks and Recreation Department provides a space for the trainings. Walker is also working with the Virginia Department of Energy and others.

The week-long training sessions prepare students to take the solar installer certification exam from the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners. The trainings are led by Duane Cunningham, a defense contractor with a background in engineering who has family ties to Buckingham County through his wife.

Cunningham’s goal is to make the class as intuitive and understandable as he can. “It’s a lot of information to take in in a week,” he says. “Normally, you would spend at least two weeks or more to try to cover this information, but we’re trying to do it in one week.”

He trimmed the information presented in the class to only material pertinent to the certificate exam, and made it as hands-on as possible. Toward the end of the week, the class does an actual installation.

Working with formerly incarcerated individuals, Cunningham has found many face an almost crippling fear of failure.

“One guy, he did open up and he told me, ‘Man, I’ve had so many failures in life … I just don’t know how I would accept another failure,’” he says. “That’s when we started incorporating in class letting people know we’ve all had setbacks, we’ve all had to overcome adversity … and explain to them you’re going to fail your way to success.”

Sherrod Long went through the program in April, and credits it for helping him get hired in his current position as a quality assurance inspector for a solar company. “I had some prior experience, but this sharpened the tools in the toolbelt,” he says. “It’s a great program. They really try to get people quality knowledge that’s applicable in a growing field.”

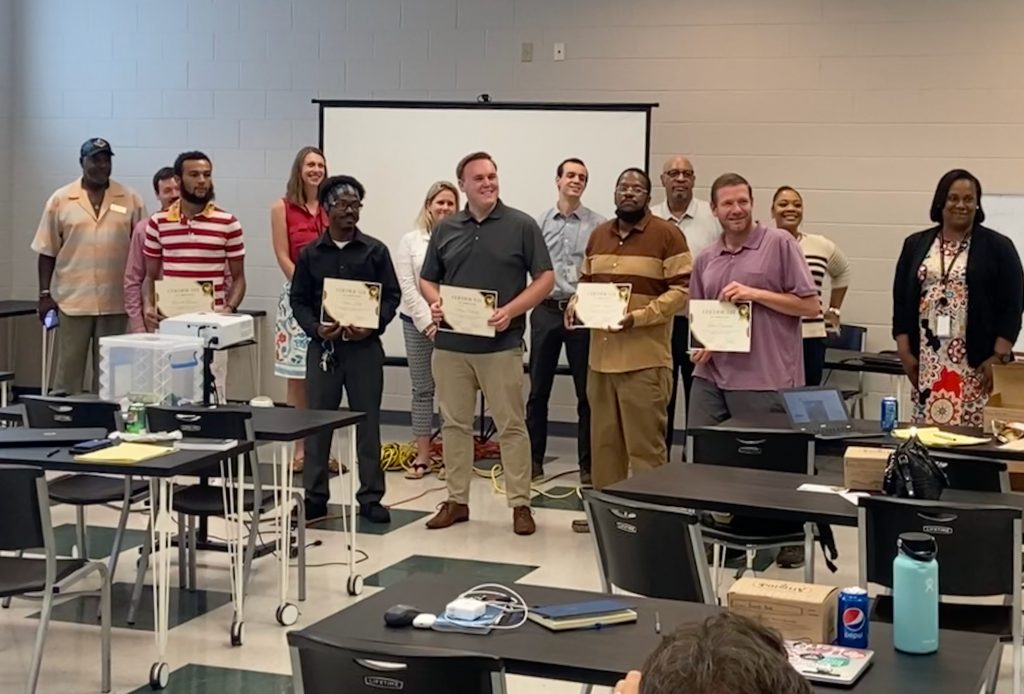

Participants in the training receive certificates at the end of the week at a luncheon that included speakers from local solar companies, the Richmond Office of Community Wealth Building, Virginia Department of Energy and Virginia Department of Corrections, among others. Photo by Dan Radmacher.

Walker doesn’t want vulnerable communities left behind in the green energy transformation.

“Our ultimate goal is to be able to train a workforce in solar so that we can be a pipeline to the numerous solar projects that are going on throughout the state of Virginia,” Walker says. “Low-income communities of color have not been included in the solar or renewable energy takeoff in the state of Virginia, the renewable energy surge that has been going on. I was determined to be a voice and be at the table. … And it’s working.”

Learn more at btgva.org

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment