Jonathan Todd points toward the pond at the focus of the workshop, while Living Web Farms landowner and director Patryck Battle looks on. Photo by Lisa Soledad Almaraz

Jonathan Todd, water systems ecologist and designer, interprets this scene as relating directly to the work he does to improve water quality. The plant life creates nutrients, which feed the fish. While perhaps only occasionally eaten by the cat, the fish can be a food source, but even more importantly they help to cycle nutrients through the water.

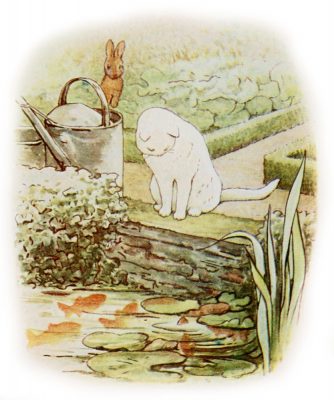

Peter Rabbit was written in England in 1902, before plumbing captured water in garden hoses. The fictional Robert McGregor’s traditional garden pond was well-designed with plants and animals present — as if the pond were lined not with cobblestones but a wetland.Jonathan Todd refers to this story as an example of permaculture, a sustainable design system integrating harmonious relationships between humans, plants, animals and the soil. He and his father, John Todd, design systems that mimic ecological processes to treat water through their company, John Todd Ecological Design.

John Todd developed a patented ecological technology that filters polluted wastewater by passing it through a series of fiberglass tanks. These tanks hold a diversity of life, from algae and fungi to plants and small aquatic animals. Sometimes the tanks are placed inside a greenhouse and grow tropical plants; for oil spill remediation, boxes of polypore mushroom spawn are added to the system.

“Any tech I wanted to create would have to have a place for all kingdoms of life,” says John Todd.

Growing up on the ocean and with experience working at sea, son Jonathan is deeply connected to water.

“It’s gotten a lot more intense and kind of intimate, repairing water and seeing how nature can do it given the opportunity,” he says. “The power of nature to heal itself is tremendous.”

The two taught a workshop in March at Living Web Farms in Mills River, N.C., to address water systems in small-scale agriculture. The Organic Growers School, an organic farming school and incubator that hosts biannual conferences in Western North Carolina, sponsored the workshop in collaboration with their spring conference.

Workshop participants discuss various solutions for streambank erosion with Todd and Battle. Photo by Lisa Soledad Almaraz

Living Web’s large pond experiences eutrophication, a condition where excess nutrients lead to algae blooms, low oxygen levels and sunlight, ultimately killing animal and plant life. Eutrophication plagues many watersheds, from Lake Erie to the Mississippi River to small ponds, especially where fertilizer runoff and industrial activity are present.

John Todd’s work over the past 30 years has helped to address eutrophication and to treat wastewater from sewage, agriculture and industry. His new book “Healing Earth,” which includes a strategy to transform strip-mined land in Central Appalachia into regenerative communities, is part memoir and part manual for creating these “biologically complex, mechanically simple” systems.

During the workshop, Jonathan Todd guided participants in redesigning the ecology and landscape around the pond to address the algae overgrowth. Some of the principal design options are explored below.

Aquaculture

Cultivating fish will help keep algae levels low as they filter it through their gills. You can grow protein for the dinner table and create higher-quality water for irrigation with the nutrients the fish deposit.

Tilapia can grow to harvestable size in just nine months. Feed them food scraps to close the loop! Aquatic scavengers, such as snails and tadpoles, will also control algae.

Flowforms

Wrought from turn-of-the-century philosophies about water’s regenerative processes and ability to harness energy, British designer John Wilkes developed clay forms in the 1960s shaped to manipulate moving water with circular or cascading designs. Mimicking the way water moves over rock, flowforms aerate water through a spiraling, corkscrew effect.

“When we put the spin back in, we’re speaking the language of water,” says workshop participant Tika Vales of Living Design Consultants. According to Vales, the spiraling effect restores an aspect of healthy ecosystems.

Wetland habitat

Plants grown along the edge of the pond help to filter runoff and aerate the water. Diversify with swamp azalea, swamp rose and wapato, or duck potato. Cattails’ early spring shoots are edible! Consider native trees and shrubs such as birch, willow, spicebush and elder. Floating water plants that cover 50 to 70 percent of the pond’s surface will reduce algae growth by limiting light penetration, according to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Using native species is imperative, as some floating water plants are invasive. If you choose other plants, establish a filter or catchment for runoff. To stabilize water edges, the Todds have successfully used spent mycelium from mushroom cultivators, which inevitably produces more mushrooms!

A permaculture practitioner can help those seeking to apply these concepts to their waterways or ponds. Farmers may be able to receive assistance from the USDA Agricultural Management Assistance program, especially for the creation of a new pond.

Come June, the Todds will return to Living Web Farms to implement the water system design developed in March. Sign up for this hands-on, all-day workshop at LivingWebFarms.org.

The benefits of ponds ripple throughout the watershed: they diversify habitat, help mitigate polluted stormwater runoff and lessen erosion from flooding. And there are personal pond perks: they attract wildlife, provide food for the table and yield naturally fertilized irrigation water.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *