Sparking Petrochemical Valley?

The Ohio River snakes alongside the construction site of the Beaver County, Pa., ethane cracker. Royal Dutch Shell broke ground on the project in November 2017. Photo by Ted Auch, FracTracker, July 5, 2016, with aerial assistance by LightHawk.

The explosion occurred in the refinery’s ethane cracker, which uses intense heat to “crack” ethane — a natural gas liquid that can be isolated from shale gas — into ethylene, a raw material for plastics manufacturing.

“My sister’s house was destroyed, and my mom’s house, too,” says Iris Brown, a former Norco resident. Norco sits along an 85-mile heavily industrialized stretch of the Mississippi River known to locals as “Cancer Alley.” Brown’s mother and sister died of what she says were pollution-related illnesses from years of exposure. Brown herself was diagnosed with asthma at 52.

More than 10 years ago, when Shell began offering housing buyouts to community members living near the facility, Brown sold her home and moved to New Orleans. After Brown moved away from Norco, a persistent rash on her hand quickly disappeared. She has since become a traveling advocate against Shell, and in 2016 spoke in Beaver County, Pa., where Shell has started constructing a new $6 billion ethane cracker.

In June 2013, an explosion at the Williams Olefins cracker plant in Geismar, La., killed two workers and injured 167. Photo courtesy of U.S. Chemical Safety Board

Although America’s petrochemical industry has historically been located along the Gulf Coast, massive natural gas liquid reserves available in the Marcellus and Utica Shale have caused many business and political leaders to look to Appalachia for the industry’s future. Shale gas production, largely driven by fracking — the process of forcing a cocktail of chemicals into the ground at high pressure to create fractures so oil and gas can be extracted — more than tripled in Appalachia from 2012 to 2017. As gas is recovered, so are other liquid hydrocarbons like the ethane used in cracker plants.

A May 2017 report by the American Chemistry Council, a trade association for the nation’s chemical companies, stated that Appalachia has the potential to become a petrochemicals and plastics manufacturing hub. The council’s report hypothesizes that at least five cracker plants will be built and suggests that “as many as nine crackers could be supported in the region.” The plants would be fed by approximately 500 miles of new or converted pipelines.

Plans for such an expansion would be centered around the Appalachian Storage and Trading Hub, an estimated $10 billion project headed by Appalachia Development Group, LLC. The hub would likely store these toxic liquids in natural underground caverns or gas wells that have already been depleted.

Plans for five cracker plants, including the one in Beaver County, Penn., have already been announced in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio — although only two are showing any signs of progress. The Beaver facility is under construction and the second plant is slated for construction right next to the Ohio River in Belmont County, Ohio. Last September, a Shell subsidiary applied for state and federal permits for the 97-mile Falcon Ethane Pipeline, which Shell estimates would be operational in 2020. Falcon would cross three states to feed 107,000 barrels of ethane a day to the Beaver County cracker plant.

A 2017 American Chemistry Council report assumes that hundreds of miles of new pipelines will be built along the Ohio and Kanawha River Valleys to feed what could be an Appalachian petrochemical hub. The red pin marks the Shell Oil ethane cracker under construction in Beaver County, Pa., which the proposed Falcon Pipeline would serve. The yellow pin marks a second cracker that is likely to happen, and gray indicates planned facilities that have shown no recent progress. Map by Cara Adeimy

People like Beaver County filmmaker and activist Mark Dixon worry about the pollution that would come with bringing another major extraction-based industry to the region.

“Nobody wants to see their community turned into a cancer alley or valley if there are better options, but Shell is leveraging the economic disadvantage in our region to push its polluting agenda onto people who are hard-pressed for better options,” Dixon says. “It’s not the market demanding that we get energy from fracked gas. It’s that the fracked gas is there and people have figured out a cheap way to make money from it, and they have captured our politicians regionally, and they have tilted the playing field to make it more economically viable.”

Adding to the Problem

According to University of Pittsburgh toxicologist James Fabisiak, southwestern Pennsylvania is “not particularly high on the list of good air quality to begin with.”

“We’re coming from a baseline that is marginal and among some of the worst in the country,” he says. “[Especially] particulate matter pollution and ozone pollution.”

In an email, Shell spokesperson Joe Minnitte stated the facility is designed “with the Best Available Control Technology and the Lowest Available Emission Rates to minimize emissions,” which are required under the federal Clean Air Act. “We also purchased emission reduction credits locally in excess of what our facility will produce, therefore increasing air quality over time.”

Since the area’s air quality is so poor, the state requires new facilities to purchase extra emission reduction credits to make sure air pollutants don’t rise above a certain limit.

In an op-ed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Fabisiak described how emissions of volatile organic compounds and nitrogen dioxide from the Beaver County cracker plant would be the equivalent of adding roughly 36,000 cars to the road.

“Shell’s own estimate for release of volatile organic compounds by the proposed plant is 484 tons per year,” Fabisiak wrote in the Post-Gazette. “The EPA estimates an average automobile driving 12,000 miles annually emits about 27 pounds. Therefore, the proposed cracker would emit about as much as 35,800 cars. Emissions of nitrogen oxides from the plant also would be about the same as 36,000 cars (the plant would release about 327 tons per year).”

Fabisiak also states that carbon dioxide emissions from the Beaver County cracker plant would be equivalent to roughly 25 to 30 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions for all of Pittsburgh — including cars, residential heating and other sources. The city’s climate action plan aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 20 percent below 2003 levels by 2023, and 50 percent by 2030.

In an email, Fabisiak wrote that “the nearly overnight addition of that single ethane cracker to Southwest [Pennsylvania], would negate, in their entirety, any benefits of the City of Pittsburgh’s climate mitigation efforts during that time.”

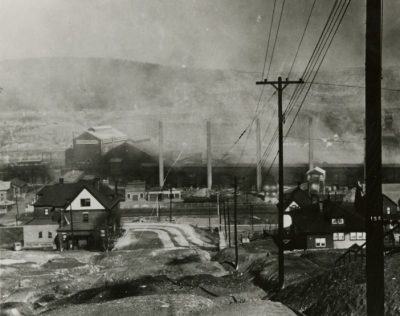

Donora, Pa., in 1949, shortly after a 1948 air inversion trapped pollutants from nearby factories on the valley floor, which led to the deaths of 20 people. Photo courtesy of U.S. National Library of Medicine

Adding to the scale of pollution is the area’s propensity for air inversions, which happen when cold air traps a pocket of warm, stagnant air — and all the pollution it contains — at ground level. A poignant example of this is the Donora, Pa., smog incident of 1948, in which pollution from local industry was trapped in the Monongahela River valley for five days, killing 20 and causing 7,000 to become ill.

“It’s the same geography that this sort of petrochemical hub is being built around, which is along the Ohio River as it goes through Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio,” Fabisiak says. “And those same geographic and climatic conditions will certainly contribute to inversions and make the situation worse.”

Both the Beaver County and Belmont County, Ohio, cracker plants would sit near the banks of the Ohio River, which is the source of drinking water for millions of people. Additionally, the American Chemistry Council projects that the five potential cracker plants would require “approximately 500 miles of pipeline running along the Ohio River valley,” as well as underground storage with “a capacity of 75 million to 100 million barrels” of natural gas liquids.

Robin Blakeman with nonprofit organization Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition expresses concern that an Appalachian petrochemical complex involving pipelines and storage alongside the Ohio River would greatly increase the likelihood of “catastrophic” water pollution.

“What they’re planning to store in these underground caverns, that will be very near the river and transported in a ‘six-pack’ pipeline that will run along the river’s edge, are very highly volatile natural gas liquid products,” Blakeman says, referring to a type of segmented pipeline that transports six different compounds.

“There rarely are any environmental or health concerns mentioned about this thing, and yet we know it will convert the Ohio River Valley into a much larger and much more dangerous ‘Cancer Alley,’ similar to the Gulf Coast,” Blakeman continues. “Are the number of jobs that would come from this, and the amount of economic development that may or may not come from this, is it all worth the very real potential of depleting or polluting the tap water for three to five million people?”

Shell began construction on an ethane cracker on the banks of the Ohio River in Beaver County, Pa., in November. Photo courtesy of Shell Cracker Impact

Beaver County resident Joanne Martin worries that the cracker plant is “the foot in the door” for the petrochemical industry.

“We don’t want a plastics industry here,” Martin says. “We don’t want this to become toxic valley, and to mirror what happened in Houston and Louisiana; we want this to become a green belt.”

“I get the sense that the Shell plant is like the tip of the iceberg and we don’t see what’s under the waterline,” she says.

Expansion Plans

On Jan. 3, the U.S. Department of Energy invited Appalachia Development Group to apply for a $1.9 billion loan guarantee for the storage hub. In March, a bill spearheaded by Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., that would ensure the hub qualifies for the federal loan cleared the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

“The Appalachian Storage Hub will allow West Virginia and its neighbors to realize the unique opportunities associated with Appalachia’s abundant natural gas liquids like ethane, naturally occurring geologic storage and expanding energy infrastructure,” Sen. Manchin told The Exponent Telegram in March.

The location of the potential Appalachian Storage and Trading Hub is still up in the air. Douglas Patchen — program director of West Virginia University’s Appalachian Oil and Natural Gas Research Consortium, which conducts research on fossil fuel technology — was a lead author on a geologic study to determine the region’s potential for underground natural gas storage. The study looked at more than 2,700 sites, including mined-rock caverns, salt caverns and depleted oil and gas reservoirs, to determine the top 30.

“I don’t think there will be a single location,” Patchen says. “It might be called the Appalachian Storage and Trading Hub, but it might be multiple surface locations linked together by pipelines.”

According to Patchen, the region needs a storage hub because “we don’t realize any of the economic benefit of the natural gas liquids in this area.”

“Right now, rather than shipping our products to Canada, Europe, South America, Asia or the Gulf Coast, there are other people here who would prefer to leave it here, keep it here and then use it here to expand the petrochemical industry and put people to work,” he says.

Cathy Kunkel — an energy analyst for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, an organization that researches economic issues connected to energy and the environment — says a regional petrochemical industry run by big oil companies would be “extracting wealth from Appalachia to benefit those companies which are obviously not based here.”

“The region has been dependent on extractive economies for the last hundred years or so, and that hasn’t really ended well as far as lifting people out of poverty,” says Kunkel. “I think before we just pursue another extraction-based industry, it’s worth having a more deliberate conversation about other economic development pathways.”

But President Donald Trump’s administration seems intent on expanding the industry. After a trip to China last November, the president unveiled a memorandum of understanding with China Energy Investment Corp., which would purportedly funnel $83.7 billion into West Virginia’s natural gas and petrochemical industry over a 20-year period. The memorandum is not legally binding, however, and was not available to the public at press time.

According to Kunkel, it’s too early to say what this agreement will mean for the region. “It could be anything from meaningless to game-changing,” she says. “Who knows?”

Matt Kelso with The FracTracker Alliance, a nonprofit organization that analyzes oil and gas industry data, is skeptical about the document.

“My understanding is that it was sort of a token that the Trump administration brought back with them to say that it was a successful economic trip to China, but it remains to be seen as to how that’s going to play out,” Kelso says.

How Big of an Impact?

According to the American Chemistry Council’s report, an Appalachian petrochemical industry including five cracker plants would create 100,818 jobs by 2025. This hypothetical analysis includes 25,664 direct jobs, 43,042 jobs in the supply chain and 32,112 jobs created by the ripple effect of workers spending their wages. But Kelso thinks these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt.

“When these new facilities get proposed, invariably they have ludicrously inflated job numbers attached to them, which then will eventually fall back to earth,” he says.

When the American Chemistry Council put forth an economic analysis of the Beaver County cracker plant in August 2011, it estimated that 17,541 permanent jobs would be created, with 2,396 of those being direct jobs at the plant. The trade association also estimated that 11,000 construction jobs would be created.

In a March email, Shell spokesperson Joe Minnitte stated that the Beaver County plant would employ “approximately 6,000 jobs during construction and 600 full-time job once the facility is operational.”

“These things are always over-inflated because it creates a good narrative upfront,” says Kelso. “By the time anybody even contests those numbers and the real numbers are actually thrown out there, people just aren’t paying attention anymore.

“But it doesn’t matter because they’ve got their permits, they’ve got their state approval and they’ve got their subsidies,” Kelso continues, “and that’s what that number was intended to do.”

As an incentive to build their cracker plant in Pennsylvania, the state gave Shell a 15-year tax amnesty window, along with a tax break valued at $1.65 billion over 25 years.

From Rust Belt to Plastic Belt

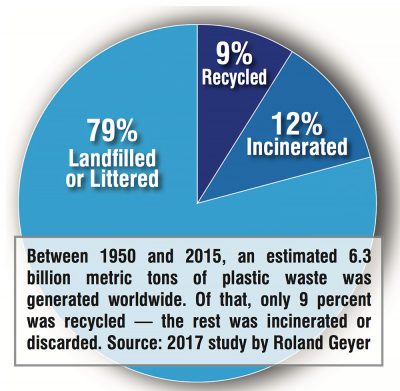

Cracker plants produce tiny, plastic pellets that are then sent off to be shaped into any number of plastic consumer products — or, more likely, the packaging for them. According to the American Chemistry Council, the largest market for plastics in 2016 was packaging. While the council claims that plastic packaging is inherently environmentally friendly due to its light weight and versatile shape, it has contributed to a massive amount of waste.

An estimated 6.3 billion metric tons of plastic waste was produced between 1950 and 2015, according to a 2017 study lead by the University of California Santa Barbara. Of this, only 9 percent was recycled and 12 percent incinerated — the remaining 79 percent was disposed of as litter or into a landfill.

Additionally, roughly half of the plastics produced during that 65-year period was created in just the last 13 years — and if trends continue, the study states that “roughly 12,000 [billion metric tons] of plastic waste will be in landfills or in the natural environment by 2050.” According to nonprofit foundation World Economic Forum, there is expected to be more plastic than fish in the ocean by 2050.

The petrochemical industry, however, is showing no signs of slowing down its plastic production. Bryce Custer, a commercial real estate advisor who established an industry team in 2016 to find the best sites for new petrochemical complexes, has stated that the Ohio River corridor has the potential to transition from the “Rust Belt” to the “Plastic Belt.”

According to Kirk Jalbert with FracTracker, a common industry response to the issue of plastic waste is to recycle more.

“Every single one of these plastic bottles is attached to a fracking well some place,” Jalbert says. “If you support the idea of expanding plastics because we can somehow do it responsibly on the end, can’t we still do it responsibly in the beginning?”

“What we’re talking about with five ethane crackers, or even just one ethane cracker, is locking the region into a long-term dependency on the oil and gas industry,” he says.

Beaver County resident Joanne Martin shares concern about the ramifications of relying on a petrochemical mono-economy.

“When there is a shift or a change in the future, I think this region again will be at risk for high unemployment,” Martin says. “And it will be difficult to transition at that point in time, unless there’s concurrent business development and alternative industries.”

A Different Vision for Beaver County, Pennsylvania

Once Shell announced its intentions in 2011 to build a cracker plant near the natural gas liquid reserves of the Marcellus Shale, several states began vying for the international company’s attention. Pennsylvania eventually won after giving Shell a 15-year tax amnesty window and a $2.10 per-gallon credit for ethane purchased from state-based drillers. The deal is valued at $1.65 billion over 25 years — the largest tax break in the state’s history, according to National Public Radio’s StateImpact Pennsylvania. Shell projects the Beaver County, Pa., cracker plant will create 600 full-time positions.

“Six hundred permanent jobs is peanuts for a $1.6 billion investment,” says Beaver County resident Joanne Martin. While she acknowledges that there could be job potential in ancillary industries Martin states that constructing another major fossil fuel industry would repeat the past.

“We don’t believe that it’s a long-term, viable business for the region,” she says. “We think it’s going to create more harm to the environment, and to the health of the people in the communities, than it is worth in terms of developing.”

Last year, Martin helped start Re-Imagine Beaver County, a grassroots initiative to bring a fossil-free community and economic development agenda to the region. The group is currently working on an alternative business plan to submit to local leaders.

“We want renewable energy businesses, we want green energy growth, we want them to invest as much money in the development of these alternative energy and green technologies as they’re putting into plastics,” Martin says. “We want businesses that are going to be here two decades from now. Not businesses that are going to cycle out like coal and steel did.”

Learn more at tinyurl.com/Re-ImagineBeaver

CORRECTION: April 16, 2018

A previous version of this article incorrectly attributed James Fabisiak as stating that carbon dioxide emissions from the Beaver County cracker plant would be equivalent to the entirety of carbon dioxide emissions from the City of Pittsburgh. As corrected above, Fabisiak stated that carbon dioxide emissions from the Beaver County cracker plant would be equivalent to roughly 25 to 30 percent of the City of Pittsburgh, which would effectively negate the city’s stated goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent by 2023.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

![“[There are] still a lot of individuals who need support, especially here in Green Cove, Whitetop, Konnarock — those are the communities up on the mountain,” says Little. “We were a part of Damascus, but because we are on the mountain outside of Damascus, a lot of the resources and help have not made their way here.” Photo by Jimmy Davidson.](https://appvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Virginia_Creeper_Trail_JMDavidson-32-1024x768.jpg)

Living less than 9 miles from the Ohio river. Our well water comes from a cave 100 feet below that is fed by a natural spring. If they poison the water source they will be poisoning the very water that flows back to the Ohio but more importantly they will be poisoning the foodsource for many who eat our produce.