The Energy Burden

Inefficient housing and financial difficulties can lead to insurmountable energy bills for rural residents

By Lou Murrey

Gerlene Wilmoth surveys the damage to the foundation of their home in Tazewell, Tenn. Photo by Lou Murrey.

Gerlene and Ronald Wilmoth of Tazewell, Tenn., had always paid their electric bill on time.

That is, until August of 2015 when Ronald suffered a stroke at the age of 55 that left him unable to use much of the right side of his body and unable to return to his job as a truck driver. Gerlene had to quit her job cleaning homes to take care of her husband. With both of them unable to work, the couple’s monthly income was reduced to just $400 a month to cover all of their expenses.

Their home is drafty and in desperate need of repairs to the roof and foundation, which has led to high electric bills and uncomfortable living conditions. It turns out that $400 a month doesn’t stretch far for residents trying to pay for everyday living expenses on top of medical bills and high utility bills.

Residents in East Tennessee, like in many places across Appalachia, spend a significant portion of their income on energy bills. When federal funding for utility payment assistance and weatherization can’t meet the need, it falls on a small number of local service agencies and churches to fill the gap. Many of these service agencies and churches already struggle to help everyone in their communities who needs it, but with threats to federal funding, they may face an even greater demand. Relief could take the form of energy efficiency programs through the Tennessee Valley Authority and local power companies.

Available Resources

For the first few months following Ronald’s stroke, he and Gerlene received aid from the few service agencies who provide utility bill payment assistance around Claiborne County. First Baptist Church of New Tazewell was able to pay one month. Manna House, a Christian charity that offers one-time bill relief, was able to pay $25 the next, and the Claiborne County Office on Aging was then able to pay for three months’ worth of bills. The Wilmoths also received the maximum available $450 from the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program known as LIHEAP, but that only covered two months’ worth of electric bills.

Then came July of 2016, when temperatures in Claiborne County consistently hovered in the low nineties. The heat was relentless, and it got especially bad for Gerlene and Ronald when the heat pump responsible for their air conditioning broke down and temperatures in their home reached 95 degrees, sending Ronald to the hospital for heat exhaustion.

As if the stress of Ronald’s hospitalization wasn’t enough, right as they reached the last little bit of their LIHEAP money, July’s electric bill arrived. Gerlene felt like she’d been socked in the gut. It was the highest one yet, at $225, and not knowing where she was going to turn for help, she started to feel a little panicky. She began making phone calls to just about everyone who had helped her before in the hope that they might be able to help again. This time she had no luck.

“I was totally freaking out,” says Gerlene. “I called so many people, and they wouldn’t have the resources to be able to help, so they would refer me to someone else, and they wouldn’t have the resources either.”

Having seemingly exhausted all of her resources, it felt like there was nowhere to turn for Gerlene. She remembers the terrifying feeling of helplessness.

“I was almost in disbelief,” she says, recalling her reaction at the time. “Like, how are we gonna pay it? They are gonna cut it off. With him being sick in July is when he had the heat exhaustion, and with that and the power bill being so high, how can we pay this? They are going to turn our power off, and we are going to smother in here.”

High Bills, High Need

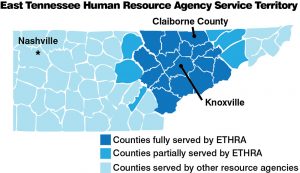

Of course, churches and service agencies intend to help as many people as possible. But, according to Terry Ramsey at the Claiborne County East Tennessee Human Resource Agency office, they are struggling to keep up with the demand. ETHRA is a regional agency that serves 12 counties, and Ramsey says, “we try to help as many people we can. We go above and beyond.”

The U.S. Department of Energy defines energy burden as the “ratio of energy expenditures to household income.” According to a 2016 study by the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy’s study “Lifting the High Energy Burden in America’s Largest Cities: How Energy Efficiency Can Improve Low Income and Underserved Communities,” the energy burden for low-income households is nearly three times higher than that of higher income households.

According to economist Roger Colton, an affordable energy burden for any household in the United States should not exceed 6 percent of a household’s gross income. Colton concluded in his 2015 study of the Home Energy Affordability Gap that low-income families were paying far more than that, depending on where they were in the country.

In East Tennessee, households earning 50 percent below the federal poverty line spend around 30 percent of their income on utilities, according to data from Colton’s firm. Gerlene and Ronald’s energy burden was around 50 percent of their household income.

The ACEEE study found that high energy burdens are primarily caused by inefficiencies in the home such as lack of insulation, leaky roofs, inefficient appliances and improper air sealing. But this is exacerbated by a person’s economic situation, high fixed utility rates and insufficient or inaccessible weatherization and bill assistance programs.

Lack of home weatherization is definitely a major factor in causing the Wilmoths’ high energy burden. “Where we don’t have the insulation and weatherization it’s too hot in the summer months and too cold in the winter months,” Gerlene says.

“My feet stay cold more than anything where the air comes up through the floor,” she says, reasoning that there can’t be much insulation under the house. In their bedroom there is a grapefruit-sized hole in the floor. She knows there are multiple roof leaks around their home because when it rains, water runs down the walls. Pointing to the kitchen, Gerlene continues, “when it rains, water blows in from the vent above the stove, and water comes in behind the stove.”

The Wilmoths have replaced all the their incandescent lightbulbs with more efficient compact fluorescents, but the major air leaks in the couple’s home resulting from improper sealing around doors and windows, a leaky roof and poor insulation are likely the greatest contributors to their high electric bill.

Where the Wilmoths live, the federal Weatherization Assistance Program is provided by ETHRA. Gerlene and Ronald are on the waiting list for ETHRA’s Weatherization Assistance Program, but the waiting list for Claiborne County alone is around 280 homes. As of November 2016, 2,709 families were on the waiting list for all 12 counties that ETHRA serves.

Steve Bandy, operations director of housing and energy services at ETHRA, reports that despite the long waiting list, the agency only has funding to complete 41 homes in the 2016-2017 budget year. At that rate it would take approximately 66 years to weatherize all the homes — if no new homes were added to the list.

Finding Relief

Part of the reason for the low number of homes being weatherized in East Tennessee is not enough funding.

“More funding would be great, if it was available, you’d be able to help more families,” says Lisa Condrey, ETHRA’s finance director of housing and energy services. “Because 41 families this year is not a whole lot. We serve 12 counties, so in some counties we are only able to serve two or three families.”

The funding ship may have sailed, though. Since 1976, funding for the Weatherization Assistance Program has been provided by the U.S. Department of Energy and has helped over 7 million families in the United States reduce their energy burden through energy efficiency upgrades to their home. On Jan. 19, the political news website The Hill reported that a blueprint of the Trump Administration’s proposed 2017-2018 budget included massive cuts to a number of government agencies, including the U.S. Department of Energy. With the new administration threatening to gut the Department of Energy, the future of the Weatherization Assistance Program is uncertain.

Weatherization improvements such as sealing leaky air ducts, adding insulation and replacing inefficient heating and cooling systems can provide a long-term fix for a high energy burden since they take care of the home inefficiencies that cause high utility bills in the first place.

For people like Gerlene who need help immediately, there is LIHEAP. Funding for LIHEAP comes from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and in Tennessee it is administered by the Tennessee Housing Development Agency through human resource agencies like ETHRA.

When Ronald Wilmoth had his heat exhaustion episode, his cat wouldn’t leave his side until the ambulance arrived. Photo by Lou Murrey

LIHEAP is the nation’s largest source of federal funding for utility bill assistance, and it is available to low-income households once in a 12-month period. Kathy Hicks, LIHEAP coordinator for ETHRA, says they receive around 5,500 applications each year from residents in the 12 counties they serve and are able to provide assistance to all of those clients.

The nonpartisan Congressional Research Service found that only about 22 percent of people eligible for LIHEAP nationwide apply. Local nonprofit organizations, churches and service agencies are left to fill in the gap, meeting the demand the best they can with the limited resources they have.

In rural areas like Claiborne County, there are only so many places to turn for energy bill payment assistance. In addition, areas served by rural electric cooperatives generally have higher energy burdens due in part to aging homes, higher electricity rates and lower average incomes, according to Rory McIlmoil, energy savings program manager at Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper.

This means a smaller number of agencies have a large gap to fill. Last year, First Baptist Church in New Tazewell, Tenn., received around 200 calls from people asking for bill assistance.

“We used to provide assistance once every six months but [the demand] was too much. It got to a point that people called every six months, and the church and the team had to come to a decision that we could only do every 12 months, and we only serve people living in Tazewell and New Tazewell,” explains Beverly, the administrative assistant at First Baptist Church, who asked that her last name not be used.

The demand for utility assistance wasn’t always so high. She explains that the church saw an uptick in demand a couple years ago when the local electric cooperative, Powell Valley Electric, ended their WeCare program, a donation-funded program that paid $50 toward the bill of members in need during the winter months. According to Powell Valley Electric, they ended the program when not enough people were donating to the fund.

Where do people like Gerlene go when they’ve exhausted all the resources available to them? Denise West, director of the Claiborne County Office on Aging, says if someone has already been to First Baptist Church and Manna House, then she sends them back to ETHRA to apply for LIHEAP again. She can also help provide assistance to people over the age of 60 through a client-needs grant from the United Way.

“If we have the resource we’ll help them, but what we can’t do is pay people’s bill month after month after month. You can’t keep doing that, there has to be some kind of change made somewhere,” West says. She worked first-hand with Gerlene to see if they could make that change and find her the help she needed. “When you see people in that shape, first of all you’re angry because it takes so long to get help, and secondly you’re more willing to help them because you know they’ve done everything they can to help themselves,” West says.

Home Improvements

Advocates in the region agree that there does have to be a change made somewhere. While these programs provide emergency assistance, they don’t address the fact that too many people are living in inefficient homes without the money, ability or programs to fix them.

There are programs in Tennessee aside from the Weatherization Assistance Program that can provide energy efficiency upgrades, but the majority of those are in cities. The Tennessee Valley Authority, which is the federally owned energy generator for most of Tennessee and parts of six other states, funded Extreme Energy Makeover programs in Knoxville, Cleveland and Oak Ridge through a 2011 Clean Air Act violation settlement. Though the funding for these programs will end in September 2017, the Knoxville Extreme Energy Makeover program will have been able to weatherize 1,200 homes.

In an August 2016 meeting between TVA staff and low-income stakeholders in Claiborne County, Gerlene and the other community members in attendance wondered why TVA couldn’t replicate the program in the more rural areas of its territory. TVA staff member Michael Scalf told community members at the meeting that while TVA “would love to see the Extreme Energy Makeover valley-wide,” there are already state programs, churches, and nonprofits already doing energy efficiency upgrades and TVA is more interested in how these entities can work better together to provide much needed services.

Increasingly, inclusive on-bill financing for energy efficiency upgrades is being adopted by rural electric cooperatives across the Southeast. An example of an inclusive model for on-bill financing is Pay As You Save, which is tied to the electric meter and would allow people living in rental and multi-family homes to receive energy efficiency upgrades and pay for them through low-interest monthly payments on their electric bill. The energy upgrades not only benefit people by reducing their energy burden and making their home more comfortable, they also lower costs for the utility.

Roanoke Electric Cooperative in Eastern North Carolina launched an on-bill finance program called Upgrade to $ave in early 2015. According to Roanoke, the first 175 participants received an average of more than $6,000 per home in efficiency improvements, including weatherization and new heating and cooling systems. Those homes are saving nearly $500 a year on their electric bills, even after accounting for repaying the utility for the initial investment. Unfortunately, Roanoke’s program is the only one available in the Southeast, outside of Kentucky.

Before the Wilmoths’ electricity could be cut off, they received Ronald’s first disability payment and were able to pay July’s $225 electric bill. Since he started getting disability the couple has not sought help for their electric bills, but they have not had any weatherization done on their home either. Their electric bill has not gone down — in December their bill was $263.

That is money Gerlene has better uses for. “I need tires for my car and can’t get ‘em because the utilities are too high,” she contends. The Wilmoths still find themselves having to decide between being comfortable in their home and having enough money for food and medical bills. “We usually try to keep the heat at 65 in the winter, but where he’s on the blood thinner he freezes to death so we have to turn it up,” she explains, referring to her husband.

While she is glad Ronald got his disability money, she is frustrated that their food assistance got reduced to just $15 a month as a result. In January, rains flooded the Wilmoths’ bathroom and bedroom, and they learned that Ronald will be needing heart surgery. Gerlene sighs, “You just can’t get ahead.”

Lou Murrey serves as the OSMRE/VISTA Tennessee Outreach Associate with Appalachian Voices. Learn more about Appalachian Voices’ energy efficiency work at appvoices.org/energysavings

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

2 responses to “The Energy Burden”

-

I greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. I’d like to respond with more information about the financing program, which I hope alleviates your concerns. First of all, the program we are advocating for is essentially “debt-free” for all participants, whether you rent or own your home/apartment. This is because if you move out, the next owner or tenant continues paying off the investment. In other words, the charge transfers from one person to the next. Secondly, that charge is capped at 80 percent of the savings achieved by the energy improvements, meaning that your electric bill goes down even though you have a new charge added to your bill. So I promise you that it’s not a gimmick. It is actually a financing model that is structured so that it provides a benefit for people of all income, while alleviating the financial burden of energy costs on those who struggle the most with their bills. Unfortunately, only a handful of electric utilities offer this program, leaving millions of low-income residents across the country with no solution to addressing their energy costs or improving the comfort of their home. Please reach out if you have additional concerns or would like more information. Thank you so much!

Rory McIlmoil, Energy Savings Program Manager

-

If I am living in a rental, I am NOT going to finance heating/cooling system upgrades on my electric bill. Weatherization yes but the landlord should pay for those improvements not the renters. That is absolutely ludicrous. Sounds like just another gimmick by the electric company to take advantage of the poor who already can’t pay.

Leave a Comment