Story and photos by Molly Moore

From a curvy, two-lane road roughly four miles from downtown Blacksburg, Va., Arlean Lambert’s property is easily recognizable. Three solar panels are mounted by a pond in front of her ranch-style home. A verdant perennial garden alongside the home, flanked with a trellis covered in hardy kiwi, completes the tranquil scene.

Lambert, a silver-haired woman with eyes that twinkle from beneath her straw farmer’s hat, isn’t the only one enjoying these 15 acres. Currently, about 65 gardeners representing 17 countries tend plots in an organic community garden behind Lambert’s home, which is run in conjunction with the YMCA at Virginia Tech and funded by the university’s Civic Agriculture and Food Systems minor.

At the Hale-Y Community Gardens, as the project is now known, most plots gently spill down a hillside. Lambert points out one, run by a Nepalese family, that’s rimmed with corn to keep plants and gardeners cool, and another that’s tended meticulously by a woman who gardens in a full burqa.

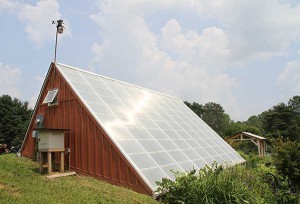

When the solar greenhouse is too hot or too cold during winters, fans cycle the air into the underground “sink,” where condensation and plant respiration combine to change the air’s temperature and moisture levels, allowing the air to resurface as a better growing climate.

In addition to the diverse open-air gardens, the property sports an unusual structure called the solar greenhouse, used throughout the year except in the hottest summer months. Where most greenhouses are subject to extremely high temperatures during summer sunshine and inhospitably low temperatures on winter nights, the solar greenhouse hosts a collection of stones and perforated pipes that, combined with a fan, store excess heat and water and release it when needed. A project of David Roper, a retired physics professor, the solar greenhouse is the first of its kind east of the Mississippi.

Lambert attributes her desire to use renewable energy to her knowledge of mountaintop removal coal mining, which she first read about in The Appalachian Voice. The seven-kilowatt solar system by the front pond powers Lambert’s home, and, closer to the gardens, a solar-powered system donated by a community member pumps water from the pond to a storage tank at an ancillary garden. The solar greenhouse fans consume the property’s only energy from the grid.

Hosting an intergenerational, international gardening community is a fulfilling retirement, Lambert says, but she’s quick to point out that she’s not a master gardener, nor did she approach this project with a set vision. “I’m just a bumbler, but I bumble with passion,” she says. “When I get into something I go in with my whole heart.”

Lambert’s parents lived on these 15 acres amidst the Appalachian mountains that Lambert once took for granted. When her husband’s job drew the couple to suburban New Jersey, Lambert realized that in heavily populated areas, green spaces often exist solely because of others’ foresight. Urban development, she says, takes over a place almost too slowly for local residents to notice.

Arlean Lambert and Jenny Schwanke gather invasive Japanese beetles from a community gardener’s plot.

After Lambert’s father passed away, her son Jacob urged her to consider the tract’s value in the face of encroaching development. Lambert discussed the idea of preserving the property with her mother, an avid gardener. When the time came, Lambert purchased the land. Several years later, she retired and began seeking ways to make the land productive.

Around the same time, the YMCA at Virginia Tech, which has a history of providing community garden space, was losing land to a cemetery expansion. David Roper was looking for a place to build his novel solar greenhouse, and the three began collaborating in 2006. Businesses and individuals donated time, materials and funds, and the next year Virginia Tech won a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to create a Civic Agriculture and Food Systems minor. The grant allowed the YMCA at Virginia Tech to hire garden coordinator Jenny Schwanke to engage students and the public and develop the gardens. Schwanke and Lambert formed a strong friendship, and today that bond serves as a foundation for a welcoming, robust community.

Even with this season’s harvest in full swing, Lambert is looking ahead, considering ways to keep the Hale-Y Community Gardens vibrant for 50 years or more. The project’s survival, she says, will come down to whether the greater Blacksburg community understands the value of these peaceful gardens and diverse relationships. Only then will people ensure that these gardens flourish for generations to come.

Do you know someone who puts their environmental principles into practice at their home or business? Nominate them for a future edition of This Green House! Email voice@appvoices.org.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment