The Emerging Efficiency Lobby: Diverse Interests Find Common Ground

Conversations about blowing up mountains for easier access to coal or risking offshore oil spills to boost a corporation’s bottom line spark passions in a way that those about financing energy efficiency retrofits don’t. But wherever national energy dialogue goes, talk of energy efficiency and minimizing our energy consumption is sure to follow.

Even in the polarized 112th Congress, energy efficiency has bipartisan support. Cutting costs is a dominant theme of the current Congress, as is job creation. Rob Mosher, director of government relations at the nonprofit Alliance to Save Energy, says that Congress should be looking for ways to address the nation’s present challenges — economic and otherwise — in ways that help financially struggling Americans.

Efficiency advocates like Mosher say that nominal investments in particular energy efficiency programs result in exponentially larger savings for consumers, businesses and government. Conserving energy, whether it comes from the sun or a nuclear reactor, benefits society as a whole through enhanced energy security, more construction and manufacturing jobs, and a lighter environmental footprint.

Although the Southeast still lags behind the rest of the country in realizing its energy efficiency potential, efficiency bills have moved forward in several of the region’s statehouses.

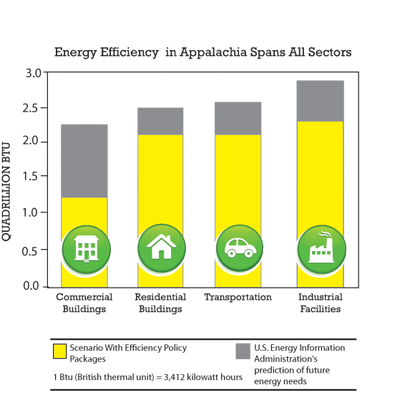

According to a 2009 report by the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance and the Appalachian Regional Commission, the implementation of a set of energy efficiency policies in Appalachia could cut energy demand by 7.3 billion kilowatt hours by 2030 — enough energy savings to offset 40 new coal-fired power plants and 182 million barrels of oil. The same study anticipated the creation of 77,300 jobs by 2030 if the region adopted the proposed efficiency policies.

The rewards of investing in energy efficiency are diverse, and so are its proponents. The Alliance to Save Energy’s associate organizations include commercial heavyweights like AT&T, energy providers such as Tennessee Valley Authority, research centers like Oak Ridge National Laboratory and nonprofits such as Habitat for Humanity. Rodney Sobin, senior policy manager at ASE, cites the chemical industry as one of the environmental community’s unlikely allies. “It’s not altruism,” Sobin says. “I think there are a lot of people who want to do the right thing, but it’s to [the chemical industry’s] own interest that energy be used efficiently across the economy because it affects the cost of their inputs.”

Often, the market encourages energy efficiency. Tennessee Valley Authority, a government-owned utility that operates in seven states, says efficiency is the cheapest way to meet energy demand. TVA delivers its energy efficiency programs at a cost of less than two cents per kilowatt hour. “No one is really in favor of wasting energy,” says Mosher. “The cheapest fuel is the one you don’t use.”

The Feds Step In

In addition to purely marketdriven motives, government can encourage efficiency. Federally, efficiency policies range from tax incentives and loans for retrofitting buildings to financing that calculates a building’s efficiency into its mortgage value.

Federal appliance standards are perhaps the government’s highest-profile efficiency tool. The poorly understood Energy Information Security Act, signed by then-President George W. Bush, requires light bulbs to produce more light per watt of electricity used. The lighting standards do not ban incandescent bulbs or force people to buy compact fluorescents. But, as the date for enforcing the lighting standards drew closer, proponents of limited government claimed that the regulations were forcing draconian rules on the marketplace.

Mosher and Sobin disagree with the notion that the lighting standards stifle the free market, and say that the light bulb rules were crafted with the lighting industry’s cooperation and have spurred innovation and increased consumer choice. Still, the backlash has made the national conversation about energy efficiency more divisive.

Possibly the most effective and least contentious way for the government to influence efficiency is by reducing its own power bill. “The federal government is the largest energy consumer in the U.S.; within the federal government the Department of Defense is the 800-ton gorilla,” Sobin says, adding that many in the defense and intelligence communities see energy as both a threat to and opportunity for maintaining national security.

Sobin says “defense hawks” have been concerned about conserving energy since World War II, when generals were running out of gas in North Africa. More recently, energy efficiency has saved lives in Afghanistan. “If you can run your facility off of solar [energy], and you can recharge your batteries, and your generator uses less fuel and your truck uses less fuel, then you have less of a vulnerability to someone blowing up fuel trucks trying to get to you,” he says. Energy efficiency strategies developed by the Department of Energy and field-tested by the Department of Defense can lead to spin-offs in the marketplace.

Graph courtesy of the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance and Appalachian Regional Commission's March 2009 report. "Energy Efficiency in Appalachia"

Energizing States

Given all the federal government can do to promote energy efficiency, much is left to the states. Traditionally, Southeastern states have implemented fewer and less aggressive efficiency policies than the rest of the country — but that may be changing.

Twenty-four states, including North Carolina and Florida, have Energy-Efficiency Resource Standards. In states that require utilities to use a certain amount of renewable energy, Energy-Efficiency Resource Standards allow utilities to count increases in ratepayer energy efficiency toward their renewable energy goals.

An even more popular route is Property Assessed Clean Energy, a financing technique that helps homeowners manage the upfront cost of energy-efficiency upgrades by paying it back incrementally in conjunction with their yearly property taxes. PACE programs are run through state and local governments. Twenty-seven states, including Virginia, North Carolina, Ohio, Georgia and Florida have PACE programs.

Efficiency proposals are also more likely to pass when a state’s big energy utilities are supportive, or at least neutral. One way to eliminate a utility’s incentive to sell more energy is to “decouple,” or separate, a utility’s income from the amount of energy it sells. That allows a utility to cover its costs, please its investors and still be indifferent toward the amount of coal or gas that goes through its doors. Half of the U.S. has programs like this for electricity, gas or both. Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina decouple gas.

By promoting energy efficiency in utility regulations, states can put more money in the pockets of ratepayers and reduce the amount of pollution the state generates.

Virginia — Open For (Efficiency) Business

In many ways, Virginia typifies the Southeast’s slow acceptance of energy efficiency as a resource. The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s 2011 state scorecard ranked the Commonwealth 34th in the nation for overall efficiency policies and 41st for utility policies alone.

Bill Greenleaf, now the executive director of the Richmond Region Energy Alliance, served on Virginia’s 2008 Commission on Climate Change. While on the Commission, Greenleaf read an ACEEE report detailing Virginia’s energy-efficiency potential and realized that increasing efficiency would be a low-cost, effective means to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Commission recommended that Virginia adopt a plan to increase energy efficiency, but in 2009 state legislators rejected the proposal and its goal of 19 percent energy savings by 2025.

“In 2009 there was no trade association for the energy efficiency industry,” Greenleaf says. “There’s an emerging business voice for the energy efficiency industry now.”

Greenleaf’s organization is one of four regional alliances in the Commonwealth that represent business contractors in fields such as heating and air conditioning, insulation and mechanics. Companies like Siemens and Johnson Controls, which provide efficiency retrofits and essentially sell energy savings to local governments, and Virginia-based energy efficiency software company OPower, also have a stake in energy policy. In July 2011, these and other businesses formed the Virginia Energy Efficiency Council, a trade organization that encourages energy conservation.

The coalition’s first challenge was to reform the way the State Corporation Commission approved energy efficiency programs. Because of the commission’s policies, the rapidly growing software company OPower — possibly the loudest pro-efficiency business voice in Virginia — couldn’t do business in its home state, even though it worked with over a dozen utilities in other states.

OPower and members of the fledgling efficiency council began simultaneously working with legislators and lobbyists to change the SCC’s approval process. The SCC had relied on a single measure, the ratepayer impact test, to determine whether to approve an energy-efficiency program. But the pro-efficiency bill that OPower and the Virginia Energy Efficiency Council favored would allow the SCC to approve programs that are able to pass three out of four cost-benefit tests instead.

The bill gained the support of the governor’s office, passed the General Assembly and was signed into law this spring. Greenleaf says the fact that utilities didn’t object helped. Their neutrality came from Virginia’s decoupled regulation that allows utilities like Dominion Power to earn money on efficiency in addition to new electricity generation.

Changing the SCC’s decisionmaking process is significant in Virginia — and according to Greenleaf, the Virginia Energy Efficiency Council is just getting started.

“We can create jobs in every city and county in Virginia if we deploy energy efficiency,” he says. Efficiency upgrades demand local labor, which helps keep jobs and taxpayer money within state borders. And by reducing homeowner utility bills, efficiency also puts money in residents’ pockets that will often be spent in-state.

“The biggest challenge is trying to get the SCC and legislature to see energy efficiency as a real resource,” Greenleaf says. “Is it more cost effective to spend $1 billion on a new power plant or is it more effective to spend $1 billion on an energy-efficiency program? … This year the Virginia Energy Efficiency Council is going to start asking that question.”

Learn more about particular energy efficiency bills currently in Congress here.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “The Emerging Efficiency Lobby: Diverse Interests Find Common Ground”

-

Very good blog, thank you so much for your time in writing the post.

Leave a Comment