A PLACE FOR SOLITUDE - National park enthusiasts fear that the proposed North Shore Road would bring development to one of the most scenic and remote forest areas in the East. Photo by Charles Seifried.

LONG TIME PASSING - Century-old cemeteries were relocated before the flooding of Fontana Lake in 1945. In the wet climate of the Smoky Mountains, they are rapidly returning to a more natural state.

Photo by Rachel Doughty.

WHERE THE ROAD ENDS, THE FUN BEGINS - Hikers take an afternoon trip to visit the site of the proposed North Shore Road. Photo by Bob Gale.

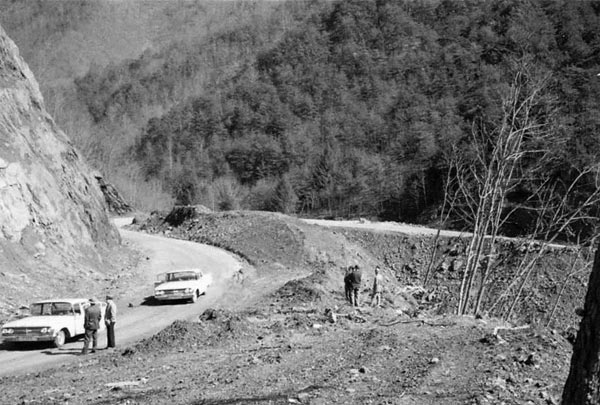

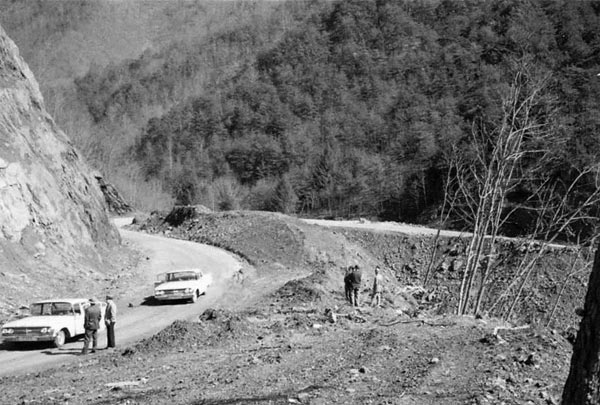

Photos from the National Park Service taken in the 1950s when the first portion of the North Shore Road was built. The photos are from a report expressing concern about the damage caused to this remote portion of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park from the preliminary phases of road construction.

The original photo caption from the Park Service report pointed out how, in the photo to the right, the fill in the ravine had, “...denuded the entire ravine area, placing the drainage on a new rock bed.” The report also called attention to how “unstable rock” from the cuts shown above had “already begun to slough down into the road bed.”

Story by Jack IgelmanPilkey Cemetery is on a small knoll surrounded by a forest of mature poplar, hemlock, pine, oak and lush green undergrowth. In the center, on the flat apex of the ridge, stands a slim tree hung with white and yellow blooms that are so bright and vivid they appear artificial from a distance. The tree is the only one among the gravestones on the knoll.

The burial ground is not meticulously manicured or ordered, but the 41 graves have been recently re-mounded and leaves have been carefully swept to the side revealing the soil’s orange hue. The clearing has allowed a thin veil of light green moss to gather in spots between the tombstones. Although some of the stones in the cemetery seem recently etched, they’ve replaced older ones that had been chiseled away by the elements. No one has been buried on the small knoll since 1941, when the last of the local residents moved away.

The state of repair is impressive considering this particular necropolis is virtually an island, isolated by a lake and the uninhabited ridges and valleys of the Great Smoky Mountains. At present, the only access to the graveyard is by water or ten-mile walk. Although no road comes near the cemetery, this may soon change.

On a cool morning in May I arrive at Fontana Marina at seven o’clock sharp on the lake’s west end. At the pier I meet Steve Shuler, a seven-year employee of the National Park Service and chief of the Cemetery Crew – a group of six men that maintain twenty-two cemeteries in the park along the lake. We board a small silver, park service craft with four other employees. I sit in the cabin while two of the crew ride in the stern accompanied by an assortment of gear, including two chainsaws, several rakes, an axe, and containers of fuel.

The lake was created in 1943 along with the completion of Fontana Dam – at 480 feet the highest dam east of the Rockies. The elongated body of water snakes frantically through a narrow corridor of the Little Tennessee River watershed for 29 miles with 238 miles of shoreline. Its placid current, slender breadth, and frequent bends conceal its length and scope, creating the illusion of a smaller, less significant body of water.

Calm as it seems, the rippling effect of the lake’s contentious beginning has churned a tidal wave that will reach a crescendo this fall. In 2007, the Great Smoky Mountain National Park (GSMNP) determine the potential fate of the largest unpaved area east of the Mississippi. The park will choose among five alternatives to resolve a 1943 agreement with residents of Swain County, North Carolina: a cash settlement to the county, a picnic area, or variations of a thirty mile road to run the entire length of Lake Fontana in the park. By way of the cemetery crew I hope to get a better grip on the clash over the proposed North Shore Road.

While researching a backpack guidebook to the region, I walked the thirty-mile Lakeshore Trail through dozens of bygone communities. The proposed road would roughly follow the trail’s path. Although the area is remote, lush, and beautiful, what captured my imagination are the thirty cemeteries scattered near the trail.

Hundreds of families were relocated to make way for the lake in 1943. While remnants of such communities as Pilkey, Forney and Proctor have been swallowed by impenetrable growth, the cemeteries have an uncanny vitality. And perhaps no one, aside from the families, is as familiar with the burial grounds as Shuler and his crew.

The morning is cool and a dense layer of low clouds makes the valley seem particularly tight. While there are pockets of development on Lake Fontana, through this section there is national forest on the right and national park on the left. And being a Tuesday and seven in the morning there are no other boats with the typical cargo of sightseers, fishermen or beer drinkers.

On the ride we exchange few words, in part because of the engine’s roar, but also because of a polite distance the group maintains with outsiders. While I live less than one hundred miles away, I am indeed viewed as an outsider. The entire crew is from the area – born and raised. Shuler himself is from Bryson City, the seat of Swain County and ground zero for the dispute over the road.

After working three years as a seasonal animal caretaker, Shuler became chief of the lake-district trail crew. In addition to shoeing park horses and shuttling visitors, his primary task is to manage the cemetery crew. Shuler speaks with a strong mountain drawl and chooses his words carefully, particularly around me. Roughly 5’9”, Shuler’s physique seems to have been designed to handle a chainsaw, which he does often. While not built like a linebacker, his shoulders are as rounded as softballs and he has the forearms of a pipe fitter. In his mid-thirties, the white hairs on his head and in his beard are beginning to outnumber the others. He is wearing work boots, green pants, and in the morning cool a park service issue fleece jacket.

The boat ride is twenty minutes across the still lake. Shuler maneuvers the craft into a small inlet below Pilkey Creek. He parks against a barge placed on the shore a week ago. The barge has enough room to haul a Suburban, which Shuler and his crew use to shuttle visitors up the steep jeep road to the cemeteries less than a mile from the inlet. Since it is not Sunday, and there are no visitors, in place of the Suburban is a green John Deere four-wheeler with a small American flag stuck behind the front seat.

Here, the group will spend two weeks preparing the area for the annual visit the NPS coordinates for folks with family buried in Posey and Pilkey cemetery. While the crew spends time at each graveyard, the majority of the two weeks is used maintaining and replacing footbridges, clearing trees, and repairing the approach trails to the cemeteries. On Sunday, at the conclusion of the two weeks, the group will assist families on their annually scheduled outing. The visitors will pay respects at most once a year. Shuler estimates that fifty to sixty people will cross the lake this coming Sunday, but that depends on the weather.

Posey Cemetery, the smaller of the two, has five plots arranged in lines like rows of crops. One of those men buried here served in the Civil War. Like many of the graveyards, Posey is on a small ridgeline. Last year, pine trees crippled by the pine beetle shadowed it. Over the winter, most of the pines fell. It took the crew more than a day of dedicated work to uncover and clean the cemetery. On the day of my visit, the ridge looked like a logging operation with sawed section of pine scattered like giant toothpicks around the ridge.

One can imagine that if undergrowth doesn’t swallow the cemeteries, fallen trees surely will. Caring for the plots is like growing fruit in the desert. The amount of work to maintain them seems absurd considering how little they are visited. The park service has been holding back the creeping flora for nearly fifty years at no small expense – at a cost of $150,000 in 2005. It begs the question, how long would it take for the cemeteries to disappear under a layer of vegetation if not for the trail crew?

Despite the kindness of the crew, they’re cautious around strangers. And lately the area has received a lot of attention because of the dividing issue that is the North Shore Road. Throwing out a question that relates to the road, the crew scatters as if the question were radioactive. Their reluctance is understandable. Many of the supporters of the road live in Swain County. Since the crew lives here too, choosing the wrong side of the issue could shake up the social order of their lives.

Away from the crew, Shuler speaks with more ease, yet with a measure of restraint. We chatted while he sharpened the teeth of his chainsaw, his attention toggled between our conversation and the tool. “We’ve got to get along with both sides,” explains Shuler, taking a break from his file. “As far as the road, whatever the park service chooses I’m behind them 100%.”

Few share Shuler’s sentiments. The North Shore Road is among the most unpopular projects in the park’s past. In fact, throughout the history of the Smokies, roads have been built rather reluctantly. Some of the early promoters of the park opposed development of grand lodges and skyline drives. “Many supported the park in the region, because any roads were welcome in Appalachia in the 1920s and thirties,” says Bob Miller, GSMNP spokesman, “but there were purists who were true conservationists.”

In that era the primary struggle of conservationists was to safeguard the Smokies from logging interests. No longer do the Smokies need to be shielded from the saw, the contemporaries of the early park protectors are more concerned with bulldozers. Though the relative scarcity of roads has preserved undeveloped space, the highways leading to and around the park have become more numerous, creating problems of a different type. “We’re the hub of this wheel. The spokes are getting bigger, but the hub isn’t,” says Miller, referring to a four-lane highway directly to Atlanta, the widening of US 321, proposed Interstate 3, and other projects in development. “There is always the potential to create new roads in the park.”

Nowhere is Miller’s prophecy of road creation more real than at the remote boundary of the park, which is located in Swain County at the terminus of Lake View Road, also known as the Road to Nowhere. In 1943, Swain County, the state of North Carolina, the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Department of the Interior agreed to build a road through the park along the north shore of Lake Fontana. Created to fuel the war effort, the lake swallowed several Swain County communities, including Pilkey, and the park added to its dominion 44,000 acres of private land on the north side of the lake.

Between 1948 and 1962, the National Park Service carved a portion of road, but unexpected costs due to the area’s steep terrain halted construction, which was not a popular decision among proud mountaineers. “The road was promised to the people of Swain County who gave up everything they had—their homes and their lives,” says David Monteith, a county commissioner and road advocate.

By the 1980’s the road movement had lost momentum. “At the time there was no expectation that the road would ever be built,” says Miller. “That’s when shuttling folks and the park’s policy to maintain cemeteries evolved.” Two decades later, in 2000, a $16 million dollar budget item to restart construction was introduced by local Congressman Charles Taylor and former North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, reestablishing hopes for a road.

Despite the ups and downs, the cemetery crew and the families maintain a steady relationship. Shuler and his crew treat visitors with great respect, yet the road is a touchy subject. The subsistence mountaineer’s legacy, dating back to prohibition and strengthened by the unfilled 1943 agreement, is a distrust and distaste for the government. Nevertheless, the families are thankful for the crew’s care. “A lot of the people appreciate the work we do, they’ll always have good remarks,” says Shuler.

While few ultimately benefit from the hard work of the cemetery crew, I sense a strong dedication to their work despite a lack of rewards. To enjoy their labor, it’s not only a prerequisite to be fond of the woods and solitude, but to appreciate history. It occurs to me that a yearning for times past is what makes the cemeteries and, more generally, the north shore of Lake Fontana so alluring: it is an extinct sliver of America. Both for opponents and supporters of the road, the north shore is a link to a long gone era. For some, abandoned homesteads and cemeteries are the connection to the past. For others, that age is nature in its purest form - places untouched by asphalt, strip malls, and billboards.

Building the road will certainly transform this area. It’s possible that a crew will not be assigned cemetery repair and maintenance. It’s hard to believe that the plots will look as fine as they do now with the strain of crowds and the crooked fragment of society that harm property, heap trash, and spoil solitude.

Among the buried in Pilkey cemetery is a woman who lived beyond 100; several are infants; and there is a substantial tombstone memorializing a couple (“Dear parents tho we miss you much we know you rest with God”). I try to imagine Pilkey as it had been: quiet, simple, peaceful. I also attempt to feel the resentment and anger of folks moved from their down-to-earth lives and isolated communities and away from their small graveyards; but my thoughts stumble. The truth is I like it as it is now. A site reclaimed by weather and intense foliage, and the absence of people. Now, it’s an uninhabited place where Shuler and his crew occasionally move leaves and drop pines with chainsaws; and one Sunday of the year families gather to eat egg salad sandwiches, drink iced tea, and pay homage to a time now departed.

For more information on the North Shore Road project and how you can provide input, see the alert on p.18.