EASTERN COUGAR - Photo courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of Natural History

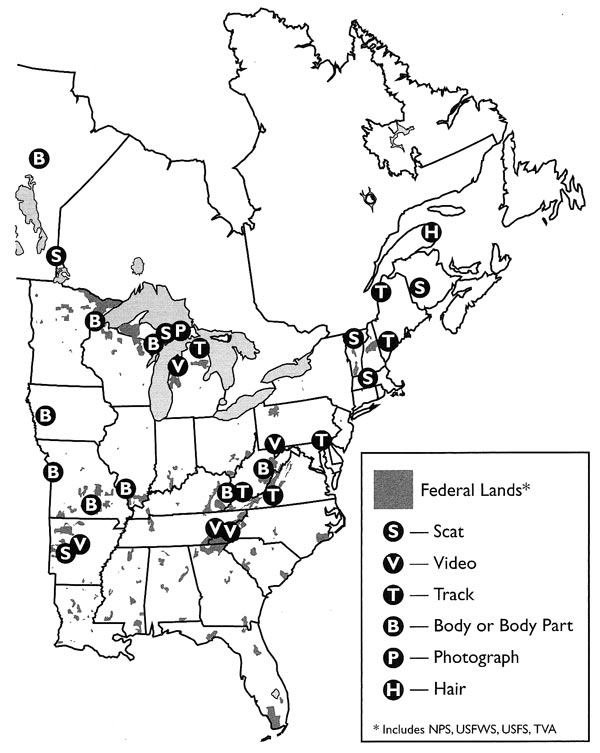

MAP OF EASTERN COUGAR SITINGS - From The Eastern Cougar: Historic Accounts, Scientific Investigations and New Evidence.

Map reproduced courtesy of Stackpole Books

images/AppalachianVoice/AVJan06/Photos/circles/Circle_Cougar.gif

“It was only natural that the earliest explorers described what they saw in terms of what they had known in Europe. Amerigo Vespucci scooped Columbus by being the first to give a name to the New World animal we know today as a cougar – actually two names, beginning the long, confusing history of multiple names for this cat. On his first voyage in 1497, skirting the Caribbean coast of Central America, Vespucci saw a land “full of animals, few [of which] resemble ours excepting lions, panthers and even these have some dissimilarities of form.”

Those dissimilarities of form would be ignored for many years. Columbus, too, in a 1503 letter to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella about his fourth and final voyage to the New World, named lions as one of the animals he saw along the coast of Central America. “I saw some very large fowls (the feathers of which resemble wool), lions, stags, fallow-deer and birds.”

What Columbus and Vespucci meant by lions and panthers were the medieval images of African lions and Asian leopards. These animals were last encountered in the flesh by Europeans during the Crusades several centuries before Columbus sailed. In medieval iconography the lion was seen as both noble and brutal; the panther was beautiful and treacherous. Over the course of the next three centuries, cougar folklore absorbed all of those ambivalent images and developed unique twists of its own.

Cougars are almost magically elusive, able to appear and disappear with hardly a trace. This characteristic made early settlers uncertain about the kind or number of cats that lurked on the frontier. It also made understanding the cat’s behavior extremely difficult, and what is not understood is often loathed. The cougar’s secretive nature even made many Native Americans uneasy; the cat seems to have been generally respected but not necessarily beloved….

… The pace of cougar encounters reported by both rural and urban residents throughout the twentieth century [has accelerated]. The response of the wildlife establishment – state and federal wildlife agency scientists and administrators, plus academic research biologists – was simple; deny, deny, deny. Sightings were attributed to delusion, deception or drunkenness. “There’s never any field evidence,” was the common refrain of the officials to whom sightings were reported – until the 1990s, when the situation changed dramatically.

Confirmed field evidence began to accumulate, and at an astonishing rate. This continued phenomenon may be due to increasing numbers of cougars throughout the East, increasing numbers of people living in rual areas, increasingly sophisticated DNA technology, or increasing interest by the press in reporting alleged encounters – or all of the above. Now, instead of dismissing the possibility of wild cougars, biologists acknowledge that there might be a few, but maintain that these cats couldn’t possibly be remnant natives and must all be FERCs (feral escaped or released captives) from subspecies other than that designated as the endangered eastern cougar.

By calling into question the genetic heritage of cougars living wild in the East, wildlife officials can sidestep the Endangered Species Act, which lists only the Florida panther (Puma concolor coryii) and the eastern cougar (Puma concolor couguar).

Never mind the intent of the act is to preserve rare life forms, or the scientific impossibility of defining unique eastern cougar genes, or the common practice of substituting subspecies from elsewhere in many official wildlife projects (including the Florida Panther Program) when the original genome is extinct or debilitated from inbreeding.

For more information on the Eastern Cougar from Chris Bolgiano, see: Mountain Lion, an Unnatural History of Pumas and People (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1995). Or visit the Cougar Network website at:

https://www.easterncougarnet.org/