Nuclear Confusion

The Complicated History of the Atom in Appalachia

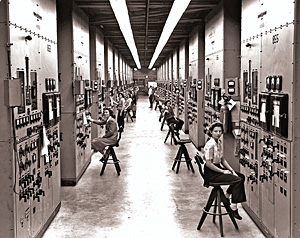

During World War II, women monitor control panels at the Y-12 plant in Oak Ridge, where Uranium one was refined to make atomic explosives. Workers toiled in secrecy without ever knowing the machinery's purpose. Photo by Ed Wescott, American Museum of Science and Energy

By Paige Campbell

Nuclear Fuel Services, Inc. sits on 66 acres between the Nolichucky River and the south end of Erwin, Tenn. This part of Erwin is the very picture of a small, blue-collar town. Within a quarter-mile of the fence surrounding the industrial site, there’s a volunteer fire department, an IGA grocery store, a United Steel Workers union hall and a tiny white church, its sign out front urging the faithful to “Take Time to Pray.” And there are houses — simple, single-story wooden homes, tidy and lively but showing their age.

Block after block of residential streets file up the hillside above the NFS complex, wedged since 1957 between Carolina Avenue and what is now Interstate 26. Considering the magnitude of what happens at the plant, it is striking to encounter it here. NFS processes highly enriched uranium for the U.S. Navy’s nuclear-powered submarines and air craft carriers, and does it in the middle of town. This is a residential neighborhood with one very imposing neighbor.

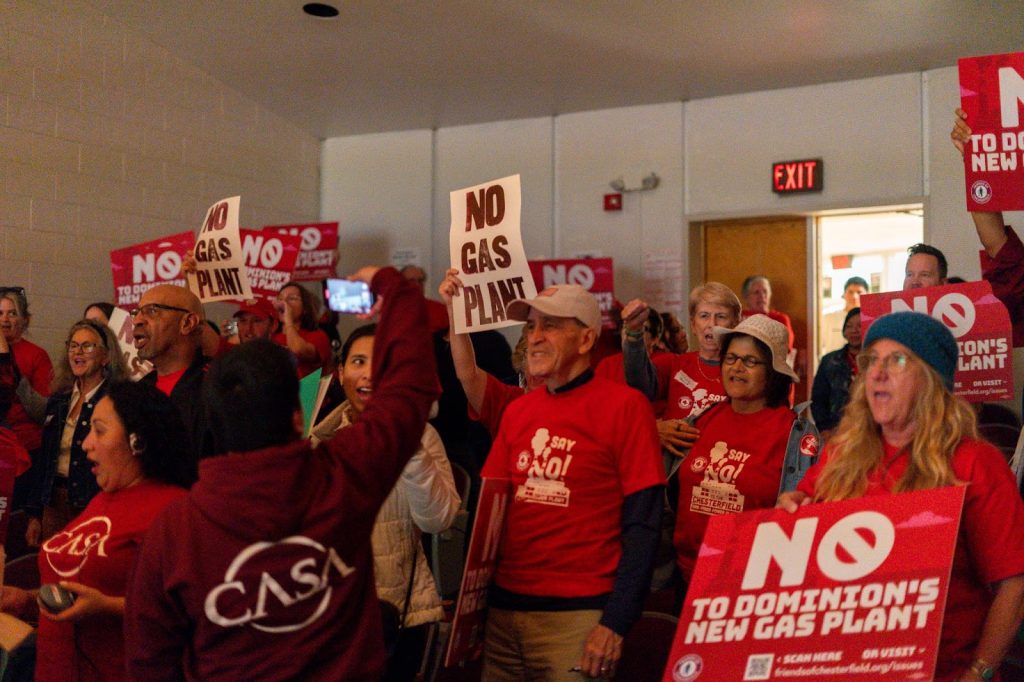

Even as sustainability-minded folks find consensus on the need to pivot away from fossil fuels, opinions are divided on what to pivot toward. Some support the expansion of nuclear power and urge skeptics to embrace nuclear as the most suitable “bridge fuel” toward a carbon-neutral future. But others stand in vigorous opposition. Greenpeace International, for instance, calls nuclear power, which currently supplies about 20 percent of U.S. energy, “an unacceptable risk to the environment and to humanity.”

In Appalachia, where the legacy of coal hangs over every conversation about energy, the possibility of nuclear expansion brings complexity. In some communities, it also brings a prospect already familiar to the region: the unwelcome responsibility of playing host to some of the energy industry’s unsavory realities.

In 1942, a momentous chapter in America’s early nuclear history began to unfold on the western edge of Appalachia, where the instant city of Oak Ridge, Tenn., was built to house the nearly 75,000 employees of the Manhattan Project. Within three years, the complex had created the nation’s first atomic weapons, including the two dropped on Japan to effectively end the Second World War.

Giant magnetic calutrons used to enrich uranium at the Y-12 plant. Photo by Ed Wescott, American Museum of Science and Energy.

According to the company’s website, this technology is a win-win and eliminates risks posed by leftover Cold War-era materials while supplying domestic power plants (representatives declined to be interviewed for this article). Yet many citizens of Erwin, concerned about the health and safety implications of having a nuclear processing plant in their backyards, have raised the same questions — about waste storage, soil and water contamination, and oversight — that have dogged the industry for decades.

Such questions prompted some state legislatures, including Appalachian states, to place restrictions on the nuclear power grid as it emerged. But recently, certain restrictions have been revisited.

A 1984 Kentucky law banned nuclear power plants in the state until a permanent federally-managed disposal facility could be established. No facility exists, but for three years in a row state senator Bob Leeper has introduced legislation to lift the ban. Leeper’s district is home to a uranium enrichment plant, and he sees clear economic benefits in allowing a reactor there as well.

Even after worldwide trust in nuclear safety soured following Japan’s Fukushima disaster in March 2011 (with U.S. public approval of new plants dropping sharply, and some nations planning to abandon nuclear entirely), Leeper vowed to try again in 2012. “We don’t get tsunamis in Kentucky,” he told the Lexington Herald-Leader.

West Virginia also banned nuclear plants in 1996. But since 2009, State Senator Brooks McCabe has proposed changing that. He envisions an energy plan based on domestic sources, including renewables like wind and geothermal; and yes, he told Beckley, W.Va.’s Register-Herald, “nuclear will have some part [in] that equation.”

Nationwide, proponents assert that despite well-known problems like the 1979 meltdown at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island, domestic nuclear plants have been consistently safe.

“There have been commercial plants operating in the United States for more than 50 years,” said Tom Kauffmann of the National Energy Institute in a 2010 Discovery News interview. “After all of those years and experience, there have been no deaths or negative health effects linked to the nuclear power plants in the public.”

But chronic mechanical problems at some older plants raise concerns about long-term maintenance. At a Vermont plant, a 2007 cooling tower collapse and various leaks convinced state officials to recommend decommissioning the reactor. They took their case to federal court — unsuccessfully — and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission granted a 20-year extension to the facility’s license anyway.

In Virginia, where commercial reactors already operate, legislators are preparing to consider another facet of the industry in 2013, when it will reevaluate the state’s 30-year ban on uranium mining.

One mining company, eyeing Pittsylvania County with its rich deposits of yellow-cake uranium, promises 300 jobs and healthy conditions for the community if the ban is lifted. But the Virginia Conservation Network supports the ban, citing higher rates of certain cancers, respiratory problems and kidney disease among people living near uranium mines.

Meanwhile, North Carolinians are revisiting the topic of nuclear waste. During the late 1980s, Sandy Mush, near Asheville in the southwest corner of the state, was evaluated as a potential federally-managed disposal site during a process that provoked significant public opposition and ultimately resulted in the selection of Nevada’s Yucca Mountain instead.

When Yucca Mountain was recently deemed unsuitable, the federal Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future was tasked with proposing a new waste disposal strategy. The Commission’s 2011 report did not suggest alternative sites, but representatives of the Nuclear Information and Resource Service believe that North Carolina’s favorable geologic features could bring attention back to Sandy Mush. And a waste site, they say, would bring risks to public health.

Back in Erwin, some 170 residents have claimed that substances handled by Nuclear Fuel Services have proved riskier than the company admits. A suit filed in June 2011 alleges personal injury, wrongful death and property damage.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission acknowledges problems at NFS, including a six-year output of radioactive technetium-99 into on-site groundwater, soil contamination at former waste lagoons and burial trenches and long-term cleanup needs at the site of a decommissioned plutonium building. More recently, a uranium accident prompted fines and a temporary shutdown when an NRC investigation found enough violations to constitute a “deficient safety culture.” But each issue, NFS says, has been handled adequately; pumps have kept Tc-99 from reaching the river, contaminated soil has been removed and the plutonium site is encased by a tent.

Yet claimants say their long-term exposure to radioactive material, including material NFS is authorized to release, has caused cancer rates to soar. While regulators insist the radiation output in Erwin is within a safe annual threshold, others argue that there may be no such thing.

“Even a single particle of ionizing radiation is capable of causing the genetic damage that could result in cancer,” Edwin Lyman of the Union of Concerned Scientists told Discovery News in 2010. “But the risk is proportional to the dose.” And the NRC-established threshold does not vary according to age or weight, Lyman added.

At an October 2011 meeting in Erwin, the National Academy of Sciences announced a study to track cancer rates near nuclear facilities. If a definitively higher rate is proven, it could prompt “radical changes” to regulations, said chairperson John Burris.

Of course, pinpointing a cancer’s trigger is notoriously difficult, Burris said, so the study will be a long-term one. To many in Erwin, though, the connection is already clear. They say the diagnoses, including those in children with adult-type brain tumors and patients with three or more separate cancers, are too numerous to be coincidental.

For Park Overall, whose property sits downstream from NFS, the lawsuit is only the latest chapter in a two-decade fight for answers about not just the plant’s output of hazardous substances, but also bigger-picture issues of oversight. How, she wonders, could the facility still be in operation after so many problems?

“The industry is out of control,” says Overall. And on the ground in Erwin, the struggles of residents to be heard louder than the industry echo so many past struggles across Appalachia. “We’ve been a sacrifice zone,” she says. “And it’s shameful.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “Nuclear Confusion”

-

I was a resident my high days in SIMI when the issue of a reactor accident 1959-1963 took place at SSFL. There has been compensation for workers at the site BUT NOTHING FOR RESIDENTS THAT HAVE SUFFERED BECAUSE OF THE ACCIDENT which includes reactor liquid waste being put down the water well and the solids being burned.

I have collected info showing that those living in SIMI have had cancer & offspring with cancer.My contact with SIMI authorities has fallen on deaf ears. My son has had leukemia, psoriasis, and arthritis [chemo, radiation treatments, …]. What do you think? Does my experience sound something like the Manhattan Project?

Leave a Comment