Guardians of our Public Lands

The employees of our state parks, national agencies and conservation organizations are committed to preserving the land we all own and enjoy. The future of our forests, air and water is in their care, and their work to protect our public lands deserves recognition and respect.

Taking Community to the Summit

By Jesse Wood

“He’s tough as nails.”

That’s how one colleague describes Larry Trivette, the superintendent of North Carolina’s Elk Knob State Park.

“He’ll work longer than anybody, than any of the volunteers and trail builders,” says Eric Heigl of the Blue Ridge Conservancy. “He’s just a leader in that regard. He’s always out front.”

For the past 32 years, Trivette has worked in the North Carolina state park system, and for more than 20 of those years, he was stationed at Stone Mountain and Morrow Mountain state parks. In 2004 – shortly after its creation to protect the headwaters of the North Fork of the New River – he became the first long-term superintendent of Elk Knob State Park in Watauga County, N.C.

An avid backpacker, hunter and fly-fisherman, Trivette grew up just down the road from Elk Knob in the community of Todd, fostering a love for the outdoors and its preservation throughout his childhood.

“I think that passion comes from growing up in a rural area and having the freedom as a child. When I was small, we didn’t worry about kids disappearing, so my sister and I would venture off into the woods and be gone all day long,” Trivette says.

“I just developed a great love for the creation that has been put here for us and wanted to be a part of seeing that preservation carried on.”

As superintendent of the park, Trivette has been instrumental in educating nearby landowners about conservation options, establishing the Elk Knob Community Headwaters Day as an annual day of celebration for locals. Heigl, who continues work with Trivette to expand the park, added that because of Trivette’s leadership, Elk Knob State Park is a part of the community.

Trivette notes that one of the highlights of his job has been the interaction with the community and working with locals to establish and preserve Elk Knob for future generations. And with urban sprawl sweeping into communities surrounding Boone and Appalachian State University, Trivette is delighted to find landowners who will sell their land to a conservancy rather than to a developer.

“That’s really been rewarding to me, to see that there are still those kinds of people out there, who could get more money possibly from developers, but have chosen not to,” Trivette says.

A 20-minute drive from downtown Boone, Elk Knob State Park consists of more than 3,400 acres and boasts the second-highest peak in the county, which rises to 5,520 feet. The park is currently in an interim developmental stage, but Trivette plans to open backcountry campsites this summer, and a wheelchair-accessible trail is in the works.

During the winter, the park is open for backcountry skiing and snowshoeing. Currently, Elk Knob State Park has one trail – a 1.9-mile trek to the summit of Elk Knob, where Trivette has stood many times, gazing into the distance. Working alongside his volunteers, Trivette actually led the effort to build the summit trail, which opened last year.

“How can you work in a place like this and walk atop Elk Knob and look off into the valleys and far-reaching mountains and not just feel so super small,” Trivette says. “It’s really something to be able to say you are a part of saving this little chunk of land and preserving it.”

Blazing Trails Toward Conservation

By Jenni Frankenburg Veal

Lifelong conservationist and Signal Mountain resident Sam Powell has helped preserve the scenic landscape of Chattanooga through his dedicated efforts to protect land and build trails for future generations. His work has made him a local hero — the road near several community schools is named after him.

Powell is one of the founding fathers of the Cumberland Trail, a scenic hiking trail that follows the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. He helped found the Tennessee Trails Association in 1968 to coordinate the development of a statewide system of hiking trails, including the Cumberland Trail, and he was a strong supporter for the passage of

Tennessee’s Trails System Act in 1971. Powell is currently chair of the Signal Mountain Parks Board.

For decades, Powell has tirelessly developed trails on the Signal Mountain section (southern end) of the Cumberland Trail in partnership with the Boy Scouts, Tennessee Division of Forestry and many other volunteers. He is celebrated for his role in constructing a number of sturdy bridges that cross streams along the trail. Powell also developed the trails at Shackleford Ridge Park on Signal Mountain, which connect the Cumberland Trail with trails along Walden’s Ridge.S

Powell’s impressive conservation resume includes helping to found the Tennessee River Gorge Trust — receiving the 1996 Adele Hampton Lifetime Achievement Award for his work with the trust — and serving on the Tennessee Conservation Commission. In 2002, Powell received the Robert Sparks Walker Lifetime Achievement Award from the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.

“I hope to continue to encourage citizens to become more active in protecting our environment and to help them understand the consequences if we don’t,” says Powell, who still works with students at Signal Mountain Middle/High School maintaining and developing the trails that surround the school. “I also look forward to continuing my work involving local parks and greenways. My hope is to see the Cumberland Trail State Park completed by the time Gov. Bill Haslam leaves office.”

A Scientist Who Really Digs Dirt

By Jamie Goodman

Stephanie Connolly’s passion for dirt began at a very early age. At three, she was working her own garden. By six, she was driving a tractor. A steadfast dream of growing up to be a farmer stayed with her through high school. But when her grandfather, a farmer himself, told her that she was too smart to stay on a farm, she did what she considered the next best thing — pursuing degrees in agriculture and soil sciences.

Raised in Morgantown, W.Va., Connolly has traveled a serendipitous circle to end up as one of the U.S. Forest Service’s top soil scientists working to protect the health of the country’s forest ecosystems. After earning a Master’s degree in soil chemistry from Colorado State University, Connolly started working for a large international corporation analyzing soil samples for projects including hydroelectric dams and gold mining. “I very quickly realized that was not the life for me,” she says. “I realized I wanted to make a difference.”

Following advice from her father to “work from the inside out,” Connolly took the national registry exam for soil scientists — a certification akin to medical examinations for doctors. She scored so well — ranking number one in the nation — that the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service immediately offered her a position. As part of her work, she spent 18 months in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park mapping how variations in soil quality affected certain rare butterfly habitats.

“North Carolina was really the turning point in my education,” she says.

Today, Connolly works her dream job with the Forest Service, helping to “manage the soils that sustain the trees that sustain the forests.” Key in her avocation is the study of how industrial emissions and climate change are affecting soil composition, which in turn affects the trees and ultimately the mammals and other species that depend on the forest. The goal, Connolly says, “[is to assess] which ecosystems will be most resilient through climate change, and do we see things in the soil that can help us determine what we should do — should we actively manage, should we passively manage, [or] should we protect.”

“This is part of our mission,” she says, “If we’re going to be responsible and proactive about our response [to changes in climate], you have to stay on top of what is going on.”

Kentucky’s “Naturalist” Treasure

By Brian Sewell

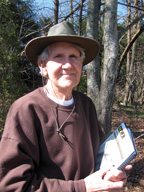

Ron Vanover, a native Kentuckian reared in McCreary County, was raised with a passion for nature, and he’s intent on passing it on to as many people as possible.

“I guess in some ways it became a family tradition,” says Vanover, the state naturalist for the Kentucky Department of Parks, of his relationship to the 50 state parks he oversees.

In 1992, Vanover became the park naturalist at Jenny Wiley State Park in Prestonsburg, Ky., where he oversaw the creation of seven miles of trails and 121 campsites. But it was in 2005, after he became the park manager at Natural Bridge State Park, that he “learned what makes the parks tick.” Now, as the state naturalist, Vanover maintains a blog and helps other naturalists promote park activities online.

Vanover also taught as an adjunct professor at Morehead State College for 10 years, and was recognized in 2009 as a “Teacher Who Made a Difference” by the University of Kentucky’s College of Education.

As a naturalist, Vanover often describes himself as a “liaison between the resource and the visitor” — a quote from the “father” of nature interpretation, Freeman Tilder.

“I love the interaction and the knowledge I can pass along to a young naturalist coming out of school,” says Vanover, whose students have since become everything from biologists to lawyers. “That’s a good feeling to know, that you’ve been able to help someone.”

A Country Kid’s Passion for Preservation

By Bill Kovarik

During the 1980s and 90s, Beth Obenshain watched as suburban developments swept away the farms around Blacksburg, Va., where she had grown up. And, as a self-described “country kid,” it bothered her.

So in 2002 she retired as a senior editor for the Roanoke Times to serve as the founding executive director of the Blacksburg-based New River Land Trust, a non-profit conservation group that encourages landowners to preserve land using voluntary easements.

“It was about saving farms, and I grew up on a farm, and I saw so much change in my life,” Obenshain says wistfully.

Now, after helping farmers and landowners place 40,000 acres of land across eight counties under easements, Obenshain looks back on almost a decade of guarding the public interest by preserving farms and historic sites.

“Conservation easements speak to Virginia’s heritage,” she says. “They are about saving the very fabric of this beautiful and historic state.”

Among sites preserved under easement are: Ingles Tavern, where Davy Crockett once stayed; and the home of Tilly Wood, who was famous for her generosity to thru-hikers on The Appalachian Trail.

“I’m incredibly elated and proud that these properties are going to be there for future generations,” she says. “[They] go back to the founding days of our country.”

Although Obenshain recently retired, she continues to work on preservation, which she says has been rewarding, and an adventure, too. “I’ve gone down little back roads, places I had never been and never would have been, if not for the land trust.”

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

2 responses to “Guardians of our Public Lands”

-

Dear Cielo,

I have never heard of any coal mining in New York state, most of the coal mining on the East Coast takes place from Pennsylvania to Tennessee, and includes West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio and Virginia.

– jamie goodman -

I enjoyed reading the article Anger in Appalachia published in “In this times magazine, August 2012′. I would like to know if the coal mining is going on in the Appalachian area that surrounds the Hudson Valley in New York.

Leave a Comment