Backlash: Counties in Alabama, Tennessee Fight Ash Relocation

Train cars loaded with coal ash, above, wait to be hauled to Perry County, Ala. for disposal.

Disposing of the coal ash spilled by TVA in December 2008 may turn out to be as much of an environmental problem as the original disaster.

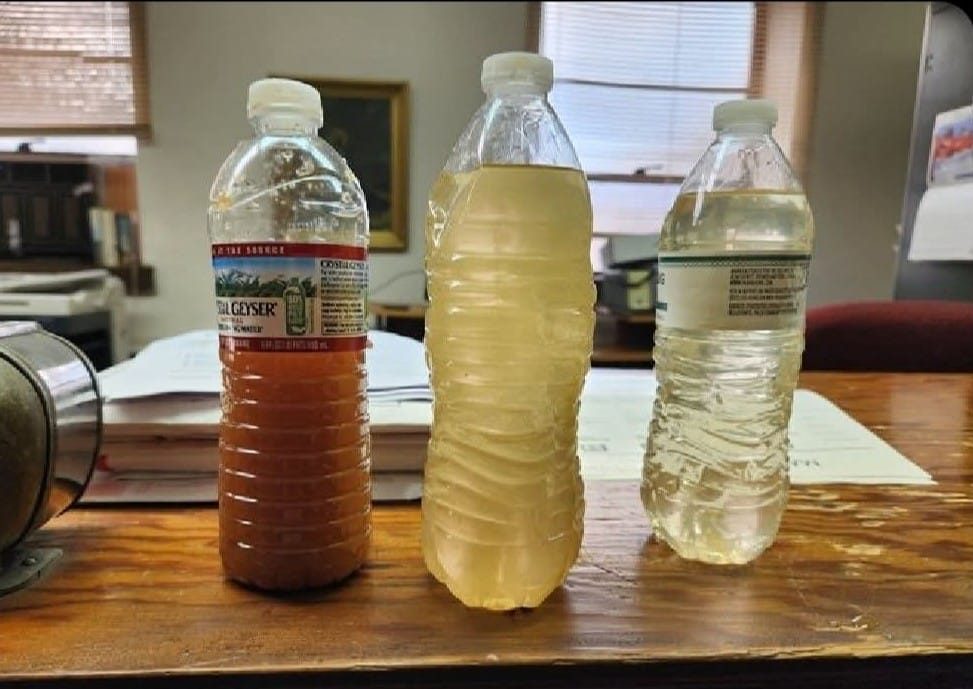

According to the Waterkeeper Alliance, toxic surface water with levels of arsenic eight times higher than drinking water standards has been found at the coal ash disposal site just outside of Uniontown, Ala.

TVA began exporting coal ash from the Harriman, Tenn., disaster site to Uniontown in July 2009, dumping it into the

Arrowhead Landfill operated by Phill-Con Services of Perry County, Ala. The company won a $95 million contract to dispose of the coal ash at their six-month-old landfill equipped with polyethylene liners and pump systems, which met EPA’s standards for contract bids.

When the first train cars full of TVA’s coal ash arrived at Arrowhead landfill, the wet ash was dumped in lined pits. Liquid that seeped out of the pile—known as leachate—was collected and trucked to the nearby Marion Waste Water Treatment Plant for sewage treatment. The processed liquid was then discharged into Rice Creek.

Perry County, in which almost 35 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, receives a $1.05 “tipping fee” per every ton of coal ash shipped. The county is expected to receive over $3 million from the coal ash shipments.

“Most of the jobs around here are low-end, low-paying labor jobs,” said County Commissioner Albert Turner, defending the ash disposal. “Taking the coal ash creates 90 higher-end jobs in construction and disposal.”

Dr. Gregory Button, director of the University of Tennessee’s Center for Disasters, Displacement and Human Rights, called the ash relocation a clear case of environmental injustice and quoted an executive order by President Clinton: “Fair treatment means that no group of people should bear a disproportionate risk share of negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, governmental, or commercial operations or policies.”

“Even if you accept the county commissioners’ rationale, it clearly underscores the asymmetrical economic power relations of this nation and demonstrates just how desperate a poor, southern minority county is in today’s America,” said Button in an article for Counterpunch magazine. Button also said that the 90 temporary jobs that would be created would hardly make a difference in a county of over 10,000.

County Residents Take Legal Action

In January, the Marion water treatment facility stopped taking Arrowhead’s leachate after attorney David Ludder filed notice of intent to sue on behalf of county residents. Ludder’s team found levels of arsenic exceeding drinking water standards in a sample taken downstream from the Rice Creek dump site.

In February, 155 residents near Arrowhead Landfill filed a notice of intent to sue for violations of the Clean Air Act.

According to Ludder, people living in homes near the landfill began to experience headaches, nausea and vomiting, noting that the odors from the dump were preventing them from leaving their homes.

John Wathen, Waterkeeper for the area, has filed a formal complaint with the EPA, stating: “People throughout the community report nightly pumping of stinking gray/tannish waste from the landfill…I have personally seen it and documented the pumps, the gray sludge leaving the site…”

Commissioner Turner called the lawsuits “frivolous and harassing,” and is considering countersuing for “interfering with a legitimate business operation.”

Also in February, Arrowhead Landfill’s actual owners, Perry County Associates, filed for bankruptcy in a Mobile, Ala., court, claiming that the landfill operator, Phill-Con and their partner Phillips & Jordan were withholding removal contract funds paid to them by TVA.

Complicating the morass of legal issues is the uncertain status of federal coal ash waste disposal regulations.

Under current EPA standards, coal ash is designated a non-hazardous solid waste. An EPA review of coal ash regulations is under way and is not expected out until late spring.

While coal ash is known to contain carcinogens and heavy metals, including arsenic, chromium, lead and mercury, coal ash itself is currently regulated as a non-hazardous material and can be disposed of in landfills permitted to handle non-hazardous solid waste.

Turner said he and other county commissioners considered the health effects of residents near the landfill and read studies by the EPA and independent sources on coal ash. The only county commissioner who did not sign off on the project was Clarence Black, representative for District 5 where the landfill is located.

For now, boxcars will continue to carry their loads of coal ash from Kingston to Uniontown while the environmental impacts of the original disaster continue to spill over into legal, social and political concerns.

Cumberland County, Tenn., Opposes Coal Ash Dump on Old Strip Mine Site

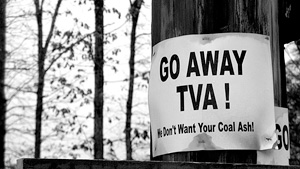

In Cumberland County, Tenn. signs posted on telephone poles reflect the sentiments of many residents concerned about the ash being deposited in their community.

Signs posted on telephone poles on Cumberland County’s Smith Mountain Road read “Go Away TVA!”

Smith Mountain Road leads to Turner Coal Mine, a surface mining site that is no longer actively operating. In June 2009,

Cumberland County Commissioners voted 11 to 5 to allow the mine to be used as a landfill for the coal ash from the Kingston spill site.

To use the mine as a landfill, the Office of Surface Mining (OSM) must grant the current owners, Crossville Coal, Inc., a revision to their permit, reclassifying the site as safe for industrial solid waste disposal.

At a Nov. 5, public hearing held by the Office of Surface Mining, 450 citizens came to submit comments on the decision.

Only one person spoke in favor of turning the mine site into a landfill: Steve Wright, whose construction company is the front-runner for the disposal contract.

“I don’t care about fly ash. I don’t know if I can eat it, I don’t know if I can put it on my garden, I don’t know if half my stuff is built of it,” said Dave Brundage, owner of the Black Cat Lodge, a substance and trauma recovery center located on the road to Turner Mine. “What I’m interested in is my property value and the safety of these roads.”

Brundage added that if the landfill were opened, hundreds of haul trucks per day would rumble past his lodge.

Brundage is also concerned about his property’s wells and natural springs. “The water runs from the top of this mountain down into the water system and the creeks. Between that mountain and my lodge I guarantee you there’s fly ash that is going to affect this place.”

Turner Coal Mine lies in the Sewanee Coal Seam. The shale surrounding the seam is particularly acidic. As a result, OSM has designated much of the land in this seam “Lands Unsuitable for Mining.”

No coal ash landfill has ever existed in the Sewanee Seam, and no studies have been done on the effects of acid mine drainage on a synthetic landfill liner like the one proposed to be used at Turner Mine.

According to the EPA’s National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) guidelines, the owners must complete a comprehensive Environmental Impact Study (EIS) before the permit change can be approved. As of this press date, no such study has been undertaken.

OSM has not made its final decision regarding the permit. Brundage and other Smith Mountain Road residents have filed a lawsuit asking a judge to review the decision of the Cumberland County Commissioners, and are awaiting a decision on their appeal.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment