Turning Coal Ash into Art

By Megan Pettey

Slabs of encapsulated coal ash were used to represent the Dan River spill and millions of tons of coal ash across the state in Armijo’s piece titled Sandbar. Photo courtesy of The Lilies Project.

Coal ash has a well-deserved, awful reputation courtesy of the numerous catastrophes that have drawn national attention, including significant coal ash spills into rivers in North Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee. Despite this harmful legacy, artist Caroline Armijo was able to find a way to uplift her community by creating art from the toxic waste that plagued her hometown of Walnut Cove, North Carolina.

The Lilies Project, created by Armijo over six years ago, is a multi-faceted way to address coal ash through community-based projects including short films, various art installations and labyrinths around the Stokes County town. The project name was inspired by the 1963 movie “Lilies of the Field,” which features the song “Amen” by Stokes County native Jester Hairston throughout the film.

In a community whose history has been tainted by coal ash for decades, The Lilies Project continues to offer positivity for the community members of Walnut Cove, even as the project expands to encompass the town’s story beyond coal ash.

A History of Coal Ash

Coal ash is the byproduct of burning coal to produce electricity, and contains chemicals such as arsenic, mercury and cadmium, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. After a drainage pipe failed in a coal ash storage pond at a Duke Energy-owned power plant in 2014, over 39,000 tons of the sooty byproduct were released into the Dan River in Rockingham County, North Carolina. It was one of the largest coal ash spills in the country’s history.

Coal ash spilled into the Dan River through this pipe when the Duke-owned Eden Steam Station failed in 2014. Photo by Appalachian Voices.

While the spill was devastating, community members had been voicing their concerns about living in close proximity to coal ash stored at power plants for years prior. The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality had previously filed lawsuits against Duke Energy in 2013 for groundwater contamination at all 14 of its coal ash facilities, resulting in a $20 million settlement. Walnut Cove residents also recall ash raining down on the community when the Duke-owned Belews Creek Steam Station began operating near the town in the 1970s.

“The coal ash issue was deeply rooted in my community,” says Tracey Edwards, former resident of Walnut Cove. “A lot of my family lived in the area. A lot of the land that Duke Power purchased came from my family when they purchased it, and my family still lived on the outskirts of what Duke Energy paid for. We knew that when the ash was actually falling back in the ‘70s, it had contaminated our soil, our water and our air at the time because you know, people often make reference to the coal ash settling on their cars, and a lot of rooftops were light gray back then.”

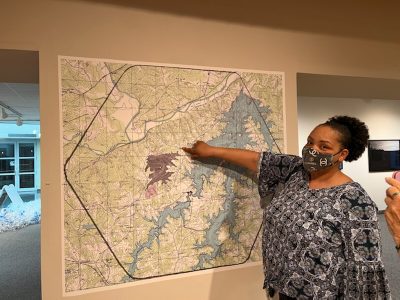

Tracey Edwards identifies her great-grandmother’s home next to the coal ash pond on a map of Walnut Cove. Photo by L. Thompson.

Edwards explains that serious illness had been plaguing the Walnut Cove community and puzzling residents for decades.

“We were really just trying to figure out why everybody’s getting so sick; why children were getting cancers, young women getting breast cancer, children getting stomach cancer, you know heart disease was running rampant,” Edwards says.

Edwards’ mother Annie Brown was close friends with Armijo, and the two began raising awareness about the possibility that illness in the community was linked to coal ash produced by the Belews Creek Steam Station. According to Ridge Graham, North Carolina program manager for Appalachian Voices, the organization that publishes The Appalachian Voice, Armijo was one of the first people to reach out to the regional environmental organization about the issue of coal ash in the area.

Having responded to the Tennessee Kingston coal ash spill in 2008, Appalachian Voices was already aware of the hazardous impacts of coal ash on physical health and environmental safety. In North Carolina, the organization tested surface and well waters, advocated for stronger regulations and organized with community members across the state through the ACT Against Coal Ash Coalition in the fight to hold utility company Duke Energy responsible for the toxic waste produced by their power plants.

After years of strife and persistence, Walnut Cove celebrated a significant victory in early 2020 when a settlement held Duke Energy responsible for digging up almost 80 million tons of coal ash at six of its power plants, including Belews Creek, and moving it to lined landfills.

Turning Toxic Waste into Art

Prior to the community’s victory, Armijo started planning The Lilies Project in 2016 with the main goal of advocating for the clean up of the coal ash basin at Belews Creek. After receiving the Creative Placemaking Grant through ArtPlace America in 2017, Armijo was able to encapsulate the coal ash from the Walnut Cove community with the help of scientists from NC State A&T University.

Armijo and the scientists designed hexagonal posts from the toxic coal ash, using polymer to prevent heavy metals from leaching into groundwater or air. The hexagon was chosen to resemble honeycombs, a symbol of “efficiency and strength,” according to The Lilies Project’s website.

“It was a long battle, and so I think the stuff that Caroline was doing with trying to find a really cool way to use coal ash instead of having it just be in some storage system or another forever, that really meant a lot to people,” Graham says.

Armijo’s coal ash art was featured as the H2O Exhibit at the Greenhill Center for NC Art this past spring. The immersive exhibit included six objects chosen by community members to represent their memories of coal ash falling over the town. Audio of each resident explaining the importance of their chosen object played overhead accompanied by their photograph displayed on a central projector, creating an intimate atmosphere that allowed visitors to hear firsthand the personal impacts of living in close proximity to the power plant.

Will Warasila took photographs of each resident, which were displayed behind their chosen objects. Photo courtesy of The Lilies Project.

Photographer Will Warasila took the images of each resident for the H2O Exhibit. During the public comment period for the Belews Creek Steam Station closure plans, these images were submitted alongside interviews from community members as official comments.

The objects featured in the exhibit included rocks, a children’s book about the environment, a wasp nest, a hymnal, a heart-shaped jewelry box and a water dipper. The dipper was selected by Edwards, who said it belonged to her great-grandmother, who lived less than a quarter mile from the improperly lined sludge pond and would care for her and her siblings while their parents worked.

“We would often walk from her house to our neighbor’s house, which wasn’t very far, and draw well water,” Edwards says. “We’d wind it up and use her dipper to dip out that cold, cold water from that well. And it was so good, I mean, oh my. It’s hard to describe how good that water really was.”

The water dipper featured in the H20 exhibit was chosen by Edwards to represent her memories of living in proximity to the coal ash pond. Photo by L. Thompson.

In an interview with the GreenHill NC curator, Armijo explained the various objects are representative of the different elements connected to their campaign. The children’s book, titled “The Sky Was Blue,” the rocks and the dipper are symbols of land, water and air, all of which were polluted by the toxic coal ash. On the other hand, the wasp nest, the hymnal and the heart remind Armijo of the strength of the community , music and love that were ingrained in Walnut Cove’s advocacy.

“I think that’s kind of the magic of art,” Armijo says. “I always say that art knows what it wants it to be and through the artistic process more information will be revealed.”

Alongside personal objects, eight hexagonal posts were suspended from the ceiling with six posts gathered in the center. A total of 14 encapsulated coal ash columns symbolizes the unity of 14 communities in North Carolina joined together for a common purpose.

Armijo designed 14 hexagonal posts from encapsulated coal ash representing communities in North Carolina affected by Duke Energy’s power plants. Photo courtesy of The Lilies Project website.

An earlier plan from the state environmental agency mandated coal ash excavation at eight Duke Energy sites, represented by the exterior columns, however coal ash sites in Allen, Belews Creek, Cliffside, Marshall, Mayo and Roxboro were excluded from original plans to remove coal ash from unlined ponds. The six interior posts represent the six communities that the state did not originally slate to be cleaned up, and which were later included in a comprehensive cleanup plan as part of the 2020 settlement against Duke Energy.

Just as Walnut Cove’s fight against coal ash was driven by faith, Armijo explained that the void in the center of the six internal posts is representative of the spirit working with and guiding community members.

In one section of the exhibit, 80 thin pavement stones created from the encapsulated coal ash were connected in a honeycomb pattern across the floor. Titled Sandbar, these stones represent the coal ash that flowed into the Dan River in 2014 as well as the 80 million tons of coal ash across North Carolina that Duke Energy must safely remove.

A collection of maps mounted to the wall of the exhibit outline each of the Duke Energy coal ash sites in North Carolina. These maps highlight how each power plant was deliberately placed near waterways that act as natural drainage for coal ash storage.

All 14 Duke Energy coal ash sites were built near small creeks, rivers and waterways as shown by Armijo’s collection of maps. Photo courtesy of The Lilies Project.

The exhibit as a whole not only represented the strength of Walnut Cove, but the communities across North Carolina who united in support of a common purpose.

“It helped to form a bond with the people in our community and people outside of our community,” Edwards says. “We bonded with people in other areas that’s going through the same thing we’re going through. It’s heartbreaking, but you know we’re forever strong. We are forever strong.”

Though the H2O exhibit ended in June, Armijo hopes to travel with the exhibit and plans on using the encapsulated coal ash in future installations.

The Lilies Project Now: Next Steps

As Armijo plans for the future of The Lilies Project, she wants to continue integrating coal ash into the project while expanding on the history of Walnut Cove beyond the impact of the power plant.

“Certainly there is the story with the power plant and the coal ash, I mean that is huge,” Armijo says. “But also with the opportunities for remediation, we could showcase that — the full spectrum of sustainability, not just the ecological devastation.”

Currently, Armijo is planning a walking tour around Walnut Cove proper that would feature more of her artwork and educate others about the town, which she aims to do with an audio edition to the tour. She’s also coordinating a driving tour, which would include the coal ash pond and other sites closer to the Belews Creek Steam Station.

“The walking tour is more cultural stuff, like it’s going to go to Rising Star, which is the church where we always had our press conferences and also where the town council meets … And then the library, which is where we had the U.S. Civil Rights Commission and we did a lot of planning meetings there,” Armijo says. “Then there’s a couple different labyrinths in town, and then there’s another church. So it’s about a dozen places.”

In 2020, The Lilies Project sponsored the installation of three labyrinths designed by Nathan Wiles around Walnut Cove as places for residents to walk, meditate and pray. Armijo is currently conducting a study on how labyrinths can be used as tools of resiliency for communities experiencing immediate impacts of climate change.

Additionally, Armijo wishes to expand on the history of Little Egypt, a mostly Black community in Walnut Cove that was flooded in the 1970s to create Belews Lake for the Duke power station. Indigenous roots of the Saura Indians, a people also known as the Cheraw, are also tied into the town’s history, which Armijo hopes to explore through The Lilies Project as well.

The Town of Walnut Cove has also adopted plans for a greenway that The Lilies Project will develop over time. Armijo’s goal is to enhance the community with parks and connect residents with natural areas in Stokes County that they otherwise wouldn’t have access to without a road or path.

The walking tour is tentatively set to be finished by the beginning of April to celebrate the third anniversary since the town’s victory in the 2020 settlement against Duke Energy.

L. Thompson contributed to this article.

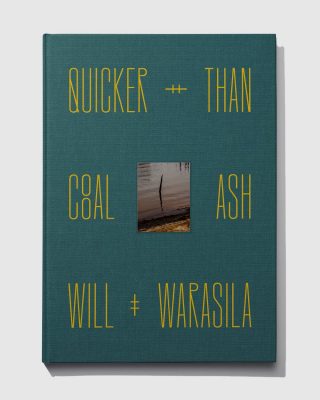

Quicker than Coal Ash

Photographer Will Warasila spent a year and a half connecting with the Walnut Cove community while creating his first photo book, “Quicker than Coal Ash.” Warasila met Caroline Armijo while attending a coal ash healing service, during which the title of his book was inspired by the quote, “bitterness will kill you quicker than coal ash.” The project portrays Warasila’s experience in Walnut Cove during the tail end of years of community activism.

“The main thing that really struck me from the very beginning is that people, especially after having spent so much time in New York, is people think of cities as being places of innovation and, you know, new ideas and new approaches,” Warasila says. “But I actually found that in rural America, here was this community that was banded together full of people from all different backgrounds, races and political beliefs, but they came around this one idea that, ‘hey we deserve to live in a clean, healthy, safe environment.’

“And through their activism and that idea they were able to set aside their differences and fight Duke Energy and in a lot of their words, righteously. And so that to me I think was the most powerful experience and eye-opening to see a community in rural America in this day and age when things are so divided come together and defeat a corporation that was poisoning them.”

“Quicker Than Coal Ash” is published by Gnomic Book.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment