Continuity of Connection: Museum Exhibition Features Contemporary Native Artwork About Indigenous Mounds

What are Indigenous mounds? How are they significant today? And how should people best care for them?

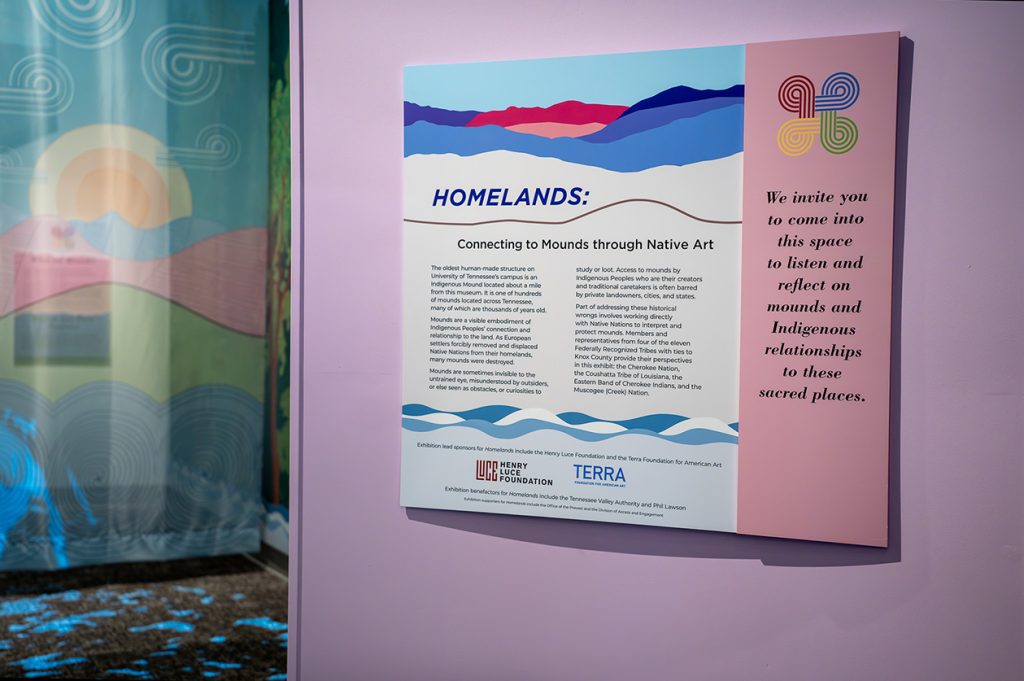

These are some of the themes explored in a new exhibition, “Homelands: Connecting to Mounds through Native Art,” at the McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. According to the exhibition, “Mounds are thoughtfully created sites representing multiple ways that Indigenous Peoples have connected to the land for thousands of years.”

“‘Homelands’ brings attention to the cultural and spiritual importance of Indigenous mounds, including the one on UT’s campus,” says Ellen Lofaro, director of repatriation at UT Knoxville.

Unlike more traditional archaeology-centric approaches — including the museum’s previous exhibition, “Archaeology and the Native Peoples of Tennessee,” which “Homelands” replaces — this exhibition showcases contemporary artwork from 17 Native artists.

“When people keep using the framework of archeology, [it] keeps putting Indigenous peoples in the past,” says Lisa King, co-curator and associate professor of English at UT, who brought the initial idea for an exhibition about mounds to the museum in 2019.

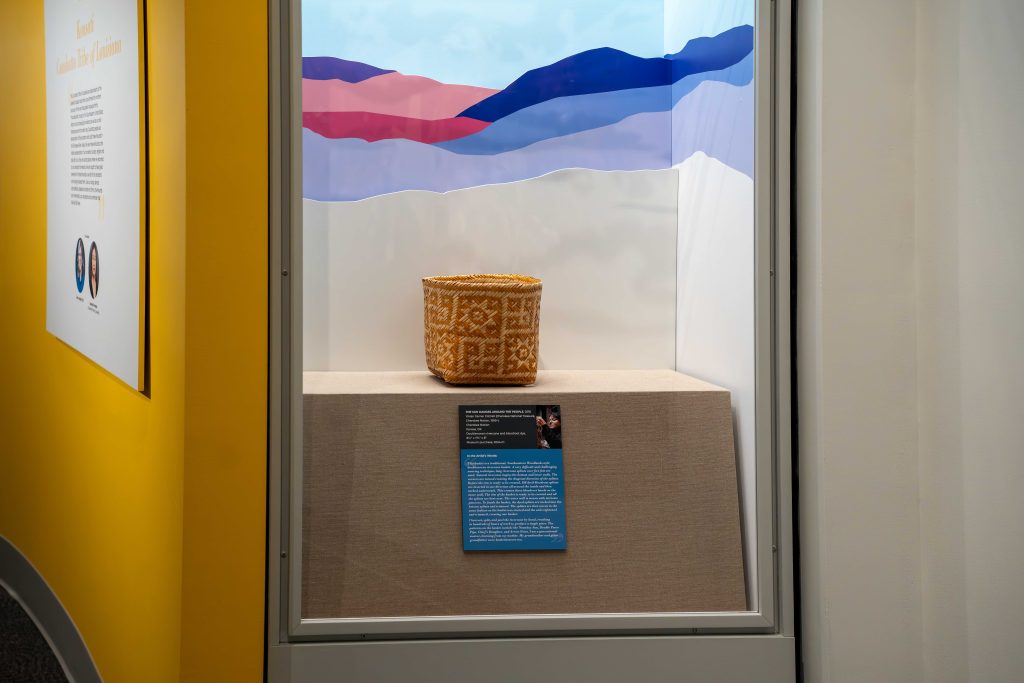

“Homelands” features art from four of the 11 Native nations with ancestral ties to UT land: the Cherokee Nation, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. All 11 Native nations were invited to participate.

To ensure the process was collaborative, each of the tribal nations selected co-curators, who in turn selected four artists to represent their respective nations. The museum chose a final, local artist, Starr Hardridge of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, whose mural is featured prominently on one wall of the exhibition. The museum has acquired 22 pieces and compensated each artist both for their art and for the artist statement that accompanies their work.

“The exhibition centers the voices of Native co-curators, who emphasize that mounds are sacred places still important to Indigenous communities today,” says Lofaro, who helped with the initial consultation and outreach efforts. “’Homelands’ explains why respecting and protecting these sites is essential.”

The original title for the exhibition was “A Sense of Indigenous Place,” which King jokes was too academic. She prefers the title “Homelands” because of its assertiveness.

“In saying ‘Homelands,’ it’s about home,” explains King, “because so often people have in their heads this narrative of removal — ‘Homelands’ reasserts place, reasserts those ties to place.”

Veering away from ‘sepia-toned’ narratives of the past

Everything, even details down to the color design for the space, was done in collaboration with Native nation partners, explains King. One request was to veer away from traditional “sepia-colored” narratives of the past.

“They wanted something open, they wanted something brighter, they wanted something that represented the landscape,” King says.

Walking into the space, visitors may be surprised to encounter vibrant colors, including purple, blue and pink, representing the mountainous landscape of East Tennessee. Additionally, four colors — blue, green, red and yellow — represent each of the four nations. Corresponding pillars, each in a different color, provide descriptions about the nation’s connection to land and mounds in both English and Native languages.

Regarding the artwork itself, museum visitors will experience a range of media — from a painting reimagining Picasso’s “Guernica,” which explores the devastation of colonialism, to an intricate turkey-feather mantle. Other pieces include a spoken-word video, an earthenware clay pot and a variety of textiles and paintings.

Other than sizing constraints and the general idea for the exhibition, it was up to each artist to determine what piece or pieces they wanted to create or feature — the majority of pieces were commissioned specifically for the exhibition, while a portion were selected because they fit the theme.

Despite the topic of mounds being discussed in the exhibition, visitors will not see the exact location or depiction of the UT mound or any others, at the request of Native nation partners. There is an inherent paradox of wanting to help people learn, respect and protect mounds, while simultaneously keeping them safe from looting, vandalism and general disrespect, explains King.

“You want increased visibility in the sense that it needs care, but increased visibility also can bring increased unwanted attention,” King says. “And so trying to strike that balance here was a real challenge.”

King also shares that despite genuine curiosity or interest about the ways these mounds were used, the public isn’t owed specific details about the ceremonial or sacred purposes of the mounds.

“They don’t need to know what’s inside the mounds,” King says. “That’s proprietary knowledge, and that’s not something the public needs to know. What the public does need to know is how to help protect them.”

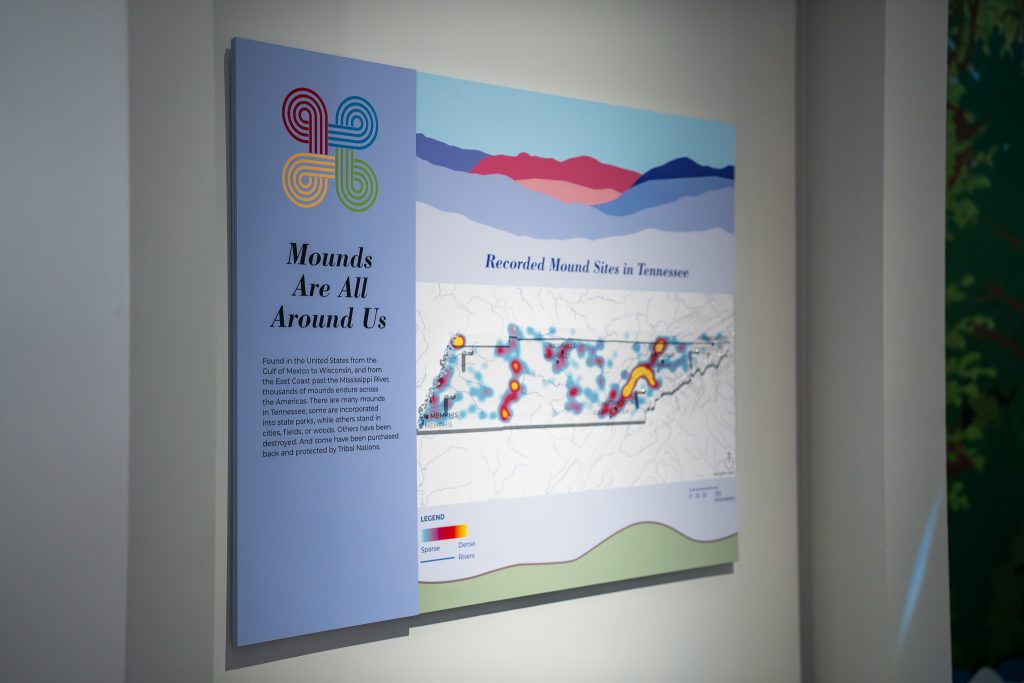

Instead, one of the first signs visitors will encounter features a heatmap depicting the volume and concentration of recorded mound sites across the state.

“Indigenous presence is everywhere in the state of Tennessee, but also, we don’t want to reveal exact locations,” King says.

Additionally, an outline of Tennessee is superimposed onto the map to emphasize the “colonial” and “ephemeral nature” of state borders, explains King.

“I don’t know if people always pick up on that, but it’s important to us,” King says. “And I love telling that part of the story — that Tennessee as a construct is overlaid on Indigenous land.”

Recognizing and addressing a ‘terrible’ history with Indigenous peoples

Going into this project, King recognizes that “UT has a terrible history when it comes to working with Indigenous peoples.” One part of this complicated past deals with the return of Indigenous remains and belongings, known as repatriation.

After years of Indigenous activism, Congress enacted the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, formalizing a federal process for the protection and repatriation of ancestral human remains and objects to lineal descendants, Native American tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. It applies to agencies and institutions that receive federal funding, such as universities and museums.

The multi-step NAGPRA process involves consultation with tribes, receiving and evaluating repatriation claims, giving public notice, and, ultimately, repatriation. Each step can take months due to the complexity and scope of the claim.

“UT was way behind,” King says.

In January 2023, ProPublica launched The Repatriation Database to highlight how, decades after the passage of NAGPRA, many universities and museums still had not repatriated thousands of remains.

The piece claims organizations leveraged a loophole in NAGPRA that allowed them to keep “culturally unidentifiable human remains.” The Department of the Interior eliminated this category and made other changes to the law in December 2023.

UT ranked No. 7 on the list of 650 institutions.

In 2016, the university hired Ellen Lofaro, now the director of repatriation. Since this time, UT’s repatriation claims have gone from 4% to 43% complete. This figure includes claims for ancestral remains both at McClung Museum and UT’s Department of Anthropology.

In 2020, Lofaro entered into her current role, managing the newly created Office of Repatriation. Additionally, the department has hired three more staffers to aid in NAGPRA repatriation and compliance.

“Everything that she’s been doing in her office has been essential and amazing, and I think laid the groundwork for Native nations to even take us seriously when we say we want to do better,” King says.

Looking ahead, the scope of the work itself is the university’s biggest challenge, explains Lofaro.

“We still have decades of work to complete these repatriations due to several factors, including tribal consultation, the number of claims and the formal paperwork process,” Lofaro says. “Often, Native nations will delay placing a NAGPRA claim until they have a suitable reburial area, which can take years, sometimes decades, to obtain. We will continue to build relationships and consult with Native nations every step of the way.”

UT is also a land-grant institution, a designation created out of the Morrill Act of 1862. The legislation awarded land and funds to states and territories to create colleges to benefit agricultural and mechanical arts.

In 2020, the High Country News released Land-Grab Universities, a comprehensive database showing how the Morrill Act awarded close to 11 million acres of Indigenous land to 52 universities. According to the reporting, “The Morrill Act worked by turning land taken from tribal nations into seed money for higher education.”

“When we’re thinking about land-grant institution obligations — I mean, any institution is on Indigenous land — but land grant institutions actually have a special obligation there that I think has not really reached full public consciousness,” King says.

Whether grappling with repatriation of Indigenous remains or acknowledgment of the impact of land-grant universities, King says, “We’re thinking about the definition of what a university is and what it does and who it stands for — these are all big questions that I don’t have answers for.”

“I think this is a process,” King continues, “and part of that process is rebuilding relationships, or developing relationships — period — with Indigenous nations, and figuring out a way to do so in a good way that honors them.”

‘A story that you probably haven’t heard’

King, who focuses on cultural rhetorics, including contemporary Native American and Indigenous rhetorics, explains that narratives of erasure and removal are still very prevalent today.

In an informal survey to get a better understanding of the non-Native audience the exhibition might reach, she found that people were curious but not well-informed about contemporary Indigenous stories.

“Most people don’t know much beyond the Trail of Tears — that they imagine Indigenous peoples in the past, or they have an inkling that they’re not gone, but they also don’t know where or how to get resources to educate themselves better,” she says.

Ultimately, King hopes the exhibition will emphasize the “continuity of connection” to land and how, even though Native nations have been forcibly removed, “the connection is still very much here.”

“If you’ve ever been curious about what do mounds mean, if you’ve ever been curious about what happened after removal, if you want to know what Indigenous peoples are doing now, come see the exhibition, because ‘Homelands’ is going to give you a story that you probably haven’t heard,” King says.

“Homelands” will run through December 2027. A website featuring a virtual tour of the exhibition is currently in the works and should remain online after the physical exhibition is complete.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment