Exports and Bankruptcies Mark Volatile Year for Coal

In 2015 and 2016, a string of coal companies declared bankruptcy as coal production dropped precipitously, hitting a low point in the second quarter of 2016. Shortly afterward, President Donald Trump was elected. Trump’s campaign focused heavily on coal, and he has continued to claim that he will bring coal jobs back. While coal has rebounded slightly, that rebound began before Trump was elected, and gains have remained modest. The national rebound hit its highest point in the last quarter of Obama’s presidency.

The slump in production in 2016 followed a record 22 coal-fired power plant retirements in 2015. The price of natural gas has remained low over the past several years, and the cost of renewables has continued to decline, leading more coal-fired plants to become uneconomical. E&E News reported that 20 coal-fired power plants retired in 2018, which doesn’t include plants that went idle or were switched to natural gas.

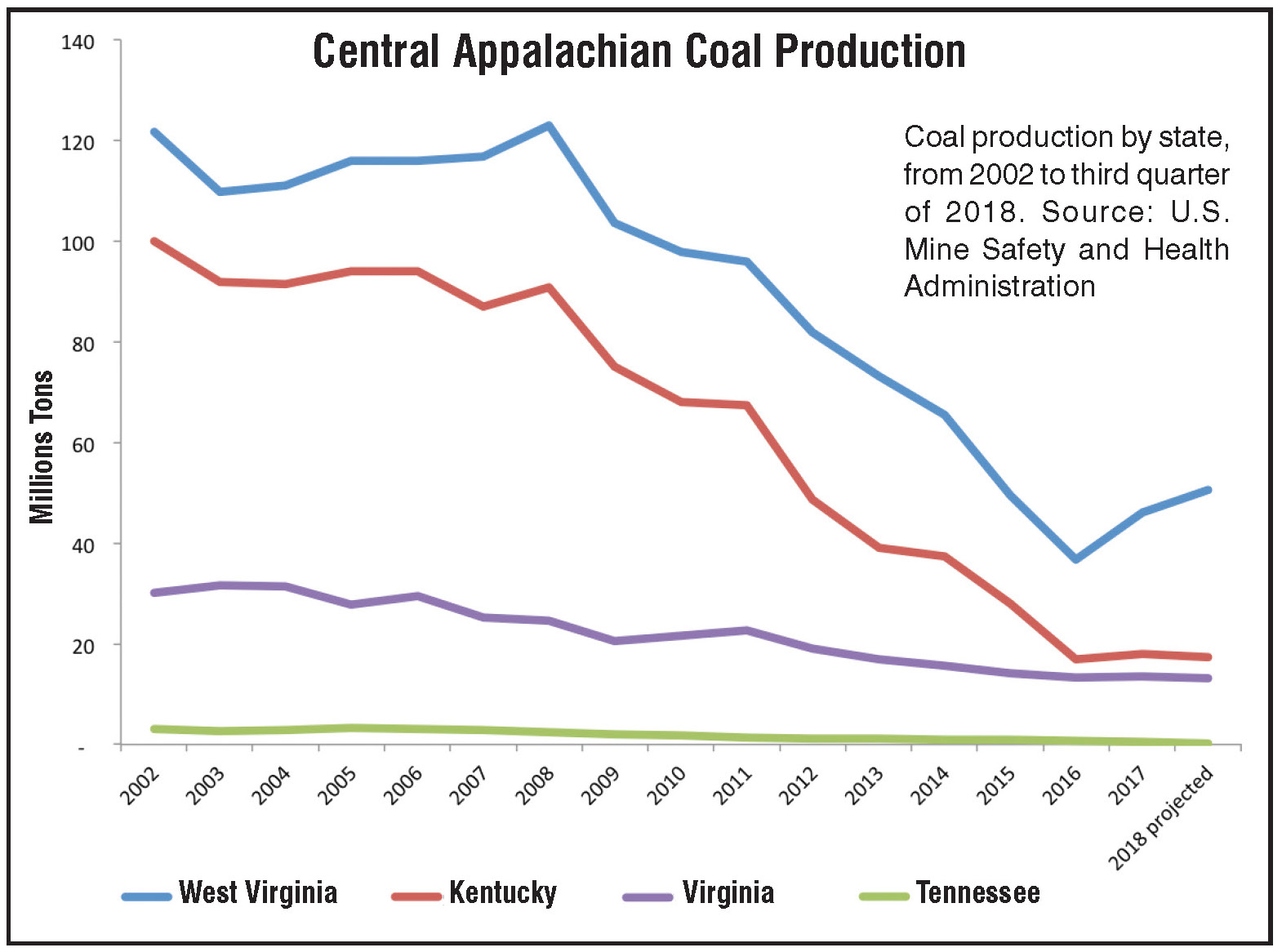

Central Appalachian coal production has been particularly hard hit in recent years. The cost of mining and transportation in the region is relatively high, making Central Appalachian coal even less competitive in the national market.

But a recent surge in the price of coal used to make steel — known as metallurgical coal — and a spike in metallurgical exports has driven an increase in production. This is especially true in southern West Virginia, where this higher-quality metallurgical coal can be found. The spike was spurred by a hurricane in Australia that shut down railways used to export the country’s metallurgical coal, and it may be short-lived, as mining and transportation costs limit export potential in the United States.

A new set of bankruptcies last fall has further highlighted the coal industry’s plight. In October, Westmoreland Coal Company and Mission Coal Company both filed for bankruptcy. Mission Coal formed early in 2018, as the latest in a long string of complicated moves orchestrated by a relative newcomer to the coal industry, Tom Clarke, who has pursued a strategy of purchasing mines out of bankruptcy.

In contrast, Westmoreland is the nation’s oldest coal company and has a long history in Central Appalachia, with more than 7,000 pensions at stake in Virginia alone, even though most of Westmoreland’s recent coal production has come from mines in Western states.

On Jan. 16, Westmoreland submitted a filing in a federal bankruptcy court requesting approval to terminate retiree benefits and its collective bargaining agreement with the United Mine Workers of America. The company has also requested $200,000 annually for 243 of its 1,723 employees through a “valued-employee program” that the union believes will come at the cost of mine workers.

Former Westmoreland employee, United Mine Workers of America member and Wise County, Va., native Bethel Brock is one of nearly 100 people who wrote a personal letter to the judge presiding over the bankruptcy hearing, asking him to be fair to miners.

“It is a shame these corporate executives are still expecting large paychecks in this bankruptcy while miners with black lung could potentially lose their benefits,” says Brock, who suffers from black lung disease himself. (Read more about black lung benefits).

Another longtime player in the Central Appalachian coal market may be doubling down on mining — Alpha Natural Resources and Contura Energy announced completion of a merger in November. Contura was created by Alpha shareholders in 2016 during Alpha’s bankruptcy reorganization, and it acquired what many saw as the more lucrative mines in the Powder River Basin, Northern Appalachia and Central Appalachia.

But Contura chose to sell its two large pit mines in Wyoming, once seen as the “crown jewels” of the company, after struggling to sell the low-heat-value coal. Presumably, the company will focus on metallurgical mines in the East. The new merger will make Alpha Natural Resources the largest metallurgical coal mining company in the country.

The recent volatility of the coal market has led to a slew of changes for the industry, and some companies appear to be banking on opportunities for short-term gain.

Similar bets on the metallurgical coal market in 2011 led to the downfall of other industry giants, like Arch Coal. Environmental advocates are quick to point out that these deals rarely work well for the communities living around mines. It remains to be seen how long the metallurgical market can prop up the coal industry.

Read more about the Westmoreland bankruptcy and Tom Clarke’s coal ventures on the Appalachian Voices blog.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment