From the Ground Up

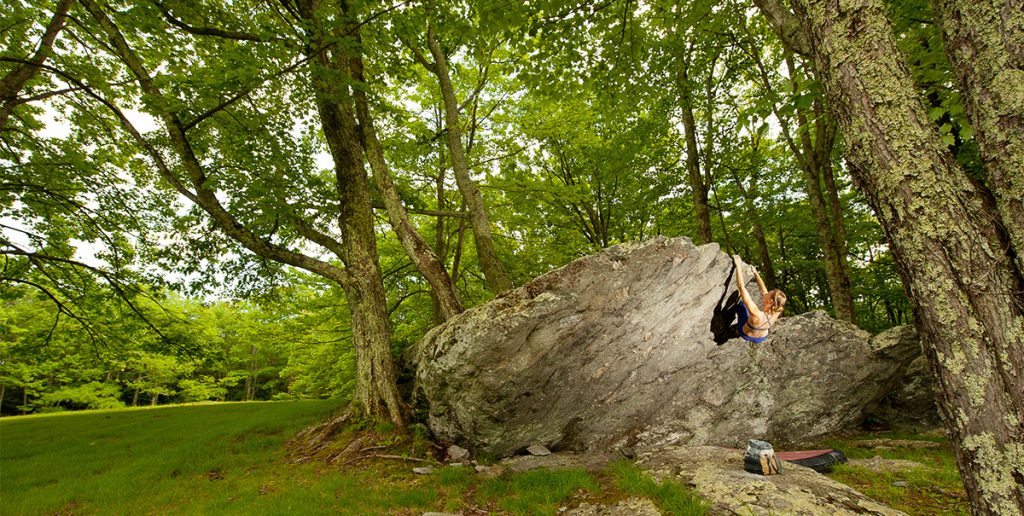

Julia Statler completes a challenging climb called “Wall Street” in the Picnic Area of Grayson Highlands. Photo by Dan Brayack

By Elizabeth E. Payne

Throughout Appalachia, roadways, trails and mountainsides are dotted with rocky outcrops that are as distinctive to the region as the rhododendron and mountain laurel that surround them. While many people may think that these rocks would be fun to climb, few have the skill to actually do it.

For decades, these rocky formations have attracted the attention of those that do.

Three styles of climbing are particularly popular in the highlands. The first is bouldering, in which a climber remains relatively near the ground while traversing established routes using no more equipment than their climbing shoes and a bag of chalk. And because the climber is rarely more than 18 feet off the ground, no ropes or safety harnesses are used. Instead, a landing pad and spotters protect against injury in the event of a fall.

The other two styles dominate in areas with cliff faces rather than boulder fields. In both, climbers use rope and safety harnesses secured to anchors positioned in the rock along the route, which protects them from falling to the ground. In sport climbing, the anchors are permanently fixed, and in traditional climbing, climbers place their own anchors as they climb.

Appalachia offers climbers challenging routes in beautiful settings, and the region’s geology invites climbers of all styles and abilities. And in return, the sport of climbing provides an opportunity for economic development for areas around these rock formations.

Building New Routes and Partnerships

At Grayson Highlands State Park, located in Grayson County in Southwest Virginia, climbers have access to over 1,000 established boulder routes and work in partnership with the park’s rangers and staff to maintain the area.

In large part, this is the result of one man’s hard work and love of climbing.

Aaron Parlier is focused on the “Eye of the Narwal,” one of many climbs along the Listening Rock Trail at Grayson Highlands. Photo by Sarene Cullen

As a young child, Parlier was introduced to climbing by his uncle, and his love of the sport was so strong that he built a small climbing wall in Afghanistan while serving with the U.S. Army — the wall was later destroyed by Taliban forces. After his deployment, he returned to Appalachia eager to get back outside and climb on rocks.

Grayson Highlands quickly drew his attention because it had so many large boulders that no one seemed to be climbing. As Parlier explored the park’s rock formations, his uncle again provided encouragement, prompting him to keep records of the routes he climbed. Several years later, that bit of encouragement developed into Parlier’s published guidebook of 349 climbs at Grayson Highlands.

But more than documenting existing climbs, Parlier also worked to establish new routes and to design and build trails that sustainably provided access to them. This work was done during the three summers he served with the AmeriCorps State Park Interpretive Program.

Parlier has also studied plants and geology in order to be a responsible steward of the areas where he develops climbs. So, when an endangered flower, the Roan Mountain bluet, was unexpectedly discovered on a single rock face at Grayson, that boulder was immediately closed to climbers.

Through his collaboration with park staff, Parlier was able to expand access for climbers, while limiting their environmental impact on the park by only designating routes where no fragile species would be affected and by building and maintaining access trails. Each Memorial Day weekend he organizes volunteers to maintain the trails he designed.

“Land Shark” is a short climb on a boulder in the Moonlight Area of Grayson, and Sheila Rahim is tackling it with style. Photo by Dan Brayack

Now, Grayson Highlands regularly attracts climbers from across the nation, and it is increasingly popular with international climbers, too.

Parlier credits the success of the project to the park’s staff, who are always available and have welcomed this collaboration with the climbing community. “The boulders are there,” he says. “So, it’s basically just facilitating access to the boulders, by means of a trail. As long as there’s folks there that can help allow it and manage the impact — in terms of travel and plant life — it can be a really great equilibrium.”

Cashing in on Climbing

Another popular climbing destination is the Red River Gorge, located near Slade in eastern Kentucky. Nestled in the Daniel Boone National Forest, this area is best known for its majestic cliff faces, which attract rope climbers. A few bouldering routes can be found there as well.

According to an Eastern Kentucky University study released in March, climbers visiting the Red River Gorge contribute $3.6 million annually to the economies of the six Kentucky counties along this geologic feature — Estill, Lee, Menifee, Owsley, Powell and Wolfe counties, some of which are among the poorest in the country.

The Access Fund, a nonprofit organization that seeks to expand access to climbing areas, co-sponsored the study and voiced support for the findings. “Climbing is an economic boon for communities across the country,” Zachary Lesch-Huie, southeast regional director for Access Fund, said in a press release. “Especially in economically distressed regions like southeastern Kentucky, it’s critical that [stakeholders] review this study and recognize the benefits climbing and other forms of outdoor recreation bring to local businesses and families. Responsibly opening more climbing areas on public land can help support a strong, sustainable and growing outdoor tourism economy.”

The town of Norton, Va., is also poised to expand its economic base by attracting climbers to the region. A strong supporter of climbing in Norton is Brad Mathisen, who is working with forest service staff in the Jefferson National Forest to carefully develop both rope climbing and bouldering routes in the Guest River Gorge.

Mathisen, who grew up in Pennsylvania and Ohio, now calls Southwest Virginia home and has been a climber for about ten years. In addition to potentially bringing economic opportunities to the region, he sees climbing as a way to change opinions about how the region’s natural resources are used.

Regional Climbing Areas

For more information about these and other places to climb, visit mountainproject.com

Chattanooga

There are many popular places to climb in and around the city of Chattanooga, Tenn. For bouldering, try Little Rock City and Rocktown. For rope climbing, try Foster Falls. And if it rains, the city also offers several indoor gyms. Visit outdoorchattanooga.com/land/rock-climbing

Hidden Valley

This popular rope climbing area near Abingdon, Va., is once again accessible to climbers. Two years ago, the Access Fund and Carolina Climbers Coalition purchased 21 acres of prime terrain in order to preserve access for everyone. Visit carolinaclimbers.org/hidden-valley.html

New River Gorge

The National Parks Service boasts that there are more than 1,400 established climbing routes along the New River Gorge National River. These steep cliff faces near Fayetteville, W.Va., are not for beginners, but will reward the more experienced climber. Visit nps.gov/neri/planyourvisit/climbing.htm

Red River Gorge

The Red River Gorge is located in eastern Kentucky within the Daniel Boone National Forest. This gorge is particularly popular for its rope climbing, but there is also some bouldering. Both guides and guidebooks are available. Visit redrivergorge.com/climbing.html

Rumbling Bald

Now part of Chimney Rock State Park, these boulders near Asheville, N.C., are particularly popular during the fall and winter months. With expanding access and parking areas, the spot offers bouldering, rope climbing across skill levels. Visit bit.ly/1V8f5xA

Recently, when discussing his climbing gear with a curious bystander, the man noticed Mathisen didn’t have an accent and asked him why he wanted to live in Norton. “I was able to say that really, as a climber, the climbing resources around here are amazing. And having the Guest River Gorge 15 minutes from our house, I love living here,” Mathisen says. “[Climbing] does provide unique opportunities to … open people’s mind maybe to different ways of using the natural resources that exist here.”

Norton town officials are particularly eager to develop bouldering at the Flag Rock Recreational Area, following an agreement to expand access reached by the city of Norton, the Access Fund and the Southwest Virginia Climbers Coalition, which was founded by Mathisen and Parlier in 2014. “We think tourism is a great opportunity, not only for the city but for the region,” Norton City Manager Fred Ramey told the Bristol Herald Courier in February 2015. “We think opportunities like this can be part of the whole tourism component.”

Gaining and Losing Access

When developing climbing in any area, securing access to the boulders can require a delicate dance between climbers, landowners and federal and state agencies. But perhaps nowhere in Appalachia has access defined the character of a climbing community as much as in Boone, N.C.

During the 1990s, climbers lost access to some of that area’s most popular climbing spots, either when they were put off limits out of environmental concern or when they were destroyed by bulldozers to make room for residential developments.

According to Parlier, this history has left its mark on the local climbing community, which continues to be fiercely protective of the areas where they can climb. He believes that no guidebook exists for the Boone area out of concern that an influx of visitors could damage the climbing areas and result in more lost access. With more maintained trails, adequate parking to accommodate the larger numbers, and additional rangers and staff to help manage the public lands, the situation may eventually change.

But for climbers serious enough to explore the available climbing through word-of-mouth and personal networks, the area has a lot to offer.

“The climbing [around Boone] is fantastic,” says Dawn Davis, a college student who transferred to Appalachian State University because of the area’s climbing. “When I moved here I didn’t know anybody, not even one person, and I made so many friends through climbing, so many wonderful friends.”

Like most climbers, Davis frequently climbs in gyms, but she says there’s something special about climbing outside. “When you climb outside, and you’re working really hard on something, you can have so many stressors in your life,” she says. “But as soon as you get on the rock, they all go away, and all you can think about is the next move or getting on top of [the boulder].”

Davis is not alone in finding pleasure in the challenge of the rocks. Climbers come to Appalachia from around the country, and around the world, to explore the highlands one boulder at a time.

From the Archives: Stewards of the Rock

The sport of bouldering was also covered in our Sept./Oct. 2010 issue, with a focus on expanding access to rocks and limiting the environmental impact to the area. Read this story and more at appvoices.org/voice20

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment