Natural Gas: Not All It’s Fracked Up To Be

When energy industry giant Halliburton invented hydraulic fracturing in the 1940s, they unlocked the potential for a natural gas boom in the United States. Now, decades later with mounting environmental and health impacts and more accurate estimates of the nation’s reserves, some feel natural gas isn’t all that it’s fracked up to be.

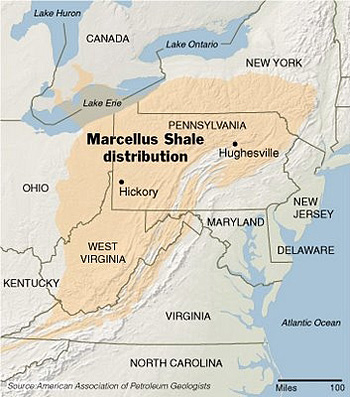

For several years, proponents of natural gas have touted the shale reserves beneath Appalachia — and other parts of the country — as clean and abundant. In fall 2007, after the scramble began for drilling permits in the Marcellus Shale, a multi-state formation that lies underneath the Appalachian Basin, Petroleum News published an article titled “Appalachia to the Rescue,” suggesting where U.S. energy salvation and independence lay.

Since then, controversial issues have emerged related to hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as “fracking.” Natural gas is the cleanest burning fossil fuel, emitting significantly less carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, sulfur oxide and mercury during combustion than oil and coal. But its extraction by fracking poses risk to water quality and the disposal of wastewater in underground wells has been linked to swarms of earthquakes.

The process requires drilling thousands of feet into shale rock formations and the high-pressure injection of enormous amounts of water, sand and chemicals, fracturing shale rock to liberate the trapped gas. As the gas travels up the well,

mere inches of concrete casing prevent its migration into surrounding ground water.

Don’t Drink the Water

In November 2011, The New York Times Magazine printed a harrowing piece on Amwell Township, Pa., a 44-acre community that experienced a proverbial gold rush five years ago. Texas-based Range Resources, a pioneer gas company in the Marcellus, came to town and sought mineral rights from landowners eager to cash in on the natural gas below their feet. But soon after, those living near drilling sites and multi-acre wastewater ponds discovered their dogs and horses mysteriously dead, litters of puppies were aborted or born with cleft lips, no hair or missing limbs and children became inexplicably ill.

Black water originating from a well corroded water-using appliances and water valves, and a smell of “rotten eggs and diarrhea” emanated from shower faucets and fouled the air outside.

Blood test results of sick Amwell residents found high levels of heavy metals such as arsenic and industrial solvents including benzene, toluene and ethylene glycol. Test results of the wastewater pond commissioned by Range Resources revealed acetone, benzene, phenol, arsenic, barium, heavy metals and methane. According to the The New York Times Magazine article, Range Resources maintained that none of the chemicals in question were found in the drinking water,

but the company did later deliver a 5,100-gallon tank of potable water to one resident after two complaints.

Seismic Awakenings

Roughly 30 miles from Amwell, the countryside of Ohio has become a dumping repository for fracking wastewater, which has been linked to earthquake swarms in the state. More than half of the disposed fluid in Ohio arrives from drilling operations in other states, such as Pennsylvania, which does not have permeable geological formations suitable for underground storage.

In the first six months of 2011, the DEP reported that 99 percent of all non-recycled wastewater from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale formation was transported to disposal wells in Ohio. One of those wells, located in Youngstown, was recently shut down along with four others in a five-mile radius after 11 earthquakes, including a magnitude 4.0 on New Year’s Eve, shook the relatively seismically stable area.

Early last year, hundreds of earthquakes shook the Fayetteville Shale Deposit in Faulkner County, Ark., leading to the permanent closure of four disposal wells and a moratorium on any future wells covering a 1,150-square-mile area. Steve Horton, a seismologist at the Center for Earthquake Research and Information, says that injection wells triggered the earthquakes. “The fact that these earthquakes happen basically right after these wells started up, and they stopped as soon as the wells stopped,” Horton says. “It’s a virtual certainty.”

After two wells in Faulkner County were used for wastewater in 2010, 923 earthquakes between Sept. 23 to March 8 — the biggest being a magnitude 4.7 — revealed the previously undetected Guy-Greenbriar Fault. Ninety-eight percent of those earthquakes happened within four miles of three of the four wells. After the wells were shut down in July, the area had six minor earthquakes – a reduction of more than 99 percent. In a peer-reviewed paper to be published in a professional seismology journal, Horton notes that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Underground Injection Control, which regulates wastewater injection wells, does not limit the proximity of these wells to seismic zones, schools, hospitals or nuclear power plants.

Researching Fracking’s Footprint

At the end of 2011, Time Magazine reported that fracking was the nation’s “biggest environmental issue” of the year, citing a very contentious study by Cornell University published last May, titled “Methane and the greenhouse gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations.”

Cornell’s Robert Howarth, Tony Ingraffea and Renee Santoro, who were also named runners-up in the magazine’s annual “Person of the Year” selection, postulated that shale gas extraction through fracking exacerbates climate change more than coal mining or oil drilling over a 20-year period as a result of methane leakage during the lifetime of a shale gas well. The researchers estimated that nearly eight percent of the methane found in shale gas leaks into the atmosphere during the fracking process.

Immediately after the Cornell University study, proponents of the natural gas industry refuted these claims. A senior vice president for engineering and technology with Range Resources told The New York Times, “That the industry would let what amounts to trillions of cubic feet of gas get away from us doesn’t make any sense. That’s not the business that we’re in.”

Other scientists have also disputed the study — including fellow colleagues at Cornell, who argued that the study was “seriously flawed” and “overestimated fugitive emissions.” In a press release from Cornell, Ingraffea clarified that their research wasn’t the “definitive scientific study” on the issue. “What we’re hoping to do with this study is to stimulate the science that should have been done before,” he said. “In my opinion, corporate business plans superseded national energy strategy.”

The EPA is currently conducting a study to assess fracking and its potential impacts on drinking water resources. The EPA identified seven locations — two prospective and five active mine sites — one of which is located in Washington County, Penn., which includes the Amwell Township. The first report is expected to be released at the end of 2012, but the final report is not scheduled for release until 2014.

According to an EPA press release, “The final study plan looks at the full cycle of water in hydraulic fracturing, from the acquisition of water, through the mixing of chemicals and actual fracturing, to the post-fracturing stage, including the management of flowback and produced or used water as well as its ultimate treatment and disposal.”

For the study, the EPA issued voluntary information requests in September 2010 from nine companies engaged in fracking. Requested information included the chemical compositions used in the extraction process. Halliburton, one of the nine companies, was subpoenaed by the EPA when it did not comply. The exact contents of the drilling fluid mixtures are not known because of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which exempts fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act. The amendment, known as the Halliburton Loophole, was spearheaded by former Halliburton CEO Dick Cheney during his vice presidency.

Fracturing the Hype

Often considered green, clean energy, natural gas is also praised for its abundance — positing the fuel as both a bridge to renewable energy and an alternative to foreign oil.

In his 2012 State of the Union Address, President Obama boasted that the U.S. has “nearly 100 years” of gas reserves. The 100-year figure is derived from a report by the industry-friendly Potential Gas Committee, which estimates that the U.S. has 100 years of “future gas supply” if consumption rates stay the same. But a closer look at the report reveals that the U.S. actually has only 11 years worth of proven reserves with “known gas reservoirs” and “existing economic and operating conditions.”

Figures for gas reserves in the Marcellus Shale seem to drop with each successive assessment. In April 2011, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated a “technical recoverable resource base of about 400 trillion cubic feet” but revised that figure to 141 trillion cubic feet this January. The U.S. Geological Survey released a report in August 2011 stating that the Marcellus Shale has 84 trillion cubic feet of “undiscovered, technically recoverable” natural gas. Based on percentages provided by USGS and the current annual consumption rate, the Marcellus Shale formation has a 50 percent probability of supplying 3.5 years worth of natural gas.

As a growing body of evidence exposes the potential environmental and health impacts of fracking, states continue to issue permits with abandon. North Carolina officials are considering legalizing the practice to reach natural gas trapped in shallow Triassic basins, while other places like Rockingham County, Va., investigated fracking’s effects on other Marcellus Shale communities and finally rejected the practice — much to the chagrin of Carrizo Oil and Gas.

Across Appalachia, the natural gas boom continues, but some cannot help but wonder if and when it will bust.

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment