Big Trouble on the Gauley

Gauley and New River Gorge residents worry that new mining operations will destroy tourism and their hopes for the future

American’s best whitewater is in big trouble.

Mountaintop removal mining has arrived. Already one trout stream is dead and another is in jeopardy.

Whitewater rafters and kayakers who flock to the region each summer and fall won’t see much difference at this point. The Gauley River still explodes through an intoxicating canyon below the Summerville Dam, and the New River still carves its

way through one of the world’s most scenic gorges.

However, rapidly expanding mountaintop removal mining is boosting the flow of sediment and toxic wastes into the rivers. As things now stand, mining will keep expanding, section by section, bite by bite, until Gauley Mountain is gone. And any hope for expanding the recreation areas downstream will disappear with the mountain.

As a result, local political leaders are raising urgent questions about the future of the region. R.A. “Pete” Hobbs, mayor of Ansted WV, warns that the new mining permits “will be extremely negative to the quality of life” in the area.

Many others are deeply worried. “What [the coal companies] are doing here is criminal,” said Kathryn Hoffman. “Say your prayers for us. It’s going to get ugly before it’s done.”

The controversy has become so bitter that a religious service at the foot of Gauley Mountain erupted into a shouting match between blue-shirted miners and praying demonstrators last April, and the sermon was never finished.

Gauley Season

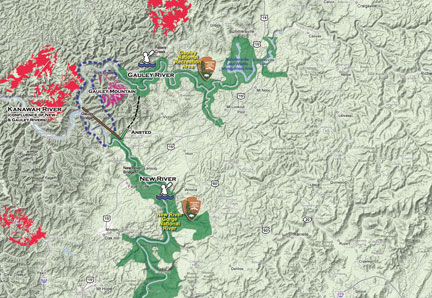

The Gauley – New River region is shaped like the head of a miner’s shovel pointed northwest, with the New River on the southwest side, the Gauley on the northeast, Gauley Mountain in between, and the town of Ansted at the base. Both rivers flow north and west, joining at Gauley Bridge to become the Kanawha, flowing down the slopes of the Allegheny Mountains into the Ohio River Valley.

The region is surrounded to the east, north and west by mountaintop removal mining operations, but until 2007, only a little mining has taken place near the Gauley and New River recreation areas.

The New River attracts more than 150,000 people for raft trips every year. It is geologically archaic, taking an unlikely course northward from the highlands of North Carolina and Virginia. Its storied history includes a 250 year old escape from captivity by Mary Ingles Draper; skirmishes during the Civil War; mine wars during the early 20th century; and one of the nation’s worst industrial disasters. (See sidebar: the Hawks Nest Disaster).

Rafting, festivals, restaurants and hospitality generates an estimated $50 million a year a year for the region.

Mining impacts

Residents are most worried about Powellton Coal Company’s mining operations on Gauley Mountain. Mining started before the permit was approved, according to state Department of Environmental Protection documents. Surveys for blasting and road use were not made before mining started, and plans for handling drainage had not been approved. All of these violations have been corrected, state officials say.

Original plans called for coal trucks to run through the town of Ansted 24 hours a day, seven days a week. When the town put up a fight, the coal company had to back off.

Yet another concern is that blasting on Gauley Mountain could blow out one of dozens of abandoned water-filled underground coal mines nearby, creating a sludge spill like the one that hit Inez, Kentucky in 2000.

“Right behind the town of Ansted there are many mine works, full of water,” said Hoffman. “It’s honeycombed back in there with old mine works. One of those ponds where they’ll be working is on top of old works. “

“When they start blasting, it’s very, very likely that we will have blowouts,” she said.

‘It will shrink your hand’

James Tawney, a farmer and a member of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, lives on 120 acres of land close enough to the Gauley River that he can hear it from his house. He grew up nearby and would come to the river with his wife when he was younger, scrambling through breathtaking, untouched forest. “The rock cliffs and waterfalls were like hidden jewels,” he said.

His dream was to establish a business to cater to whitewater enthusiasts, possibly a resort and restaurant. But now the dream is on hold as he watches mountaintop removal mining getting closer. Already a coal company has been drilling core samples on 90 of his acres where they own mineral rights.

Tawney’s land is located near Peters Creek and a section of the Gauley that, officially, has experienced only one coal slurry spill. Tawney believes the spills are constant, and that they are changing the river.

“I do see a difference in the Gauley now,” Tawney said. “I won’t swim in it.

I’ve stuck my hands into the ponds that run into the Gauley. The water is red-orange. It will shrink your hand up.”

Residents are in a “Catch-22” situation, Tawney and others say. “We don’t want to scare away the tourists,” Tawney said. “I don’t want to say, ‘hey, don’t come here because it’s getting polluted.’ But if more people knew what they were rafting in, it would change in a heartbeat.”

Mayor questions best use

The town at the center of the controversy, Ansted, has never seen anything like current controversy.

Established in 1873, and named for a British geologist, Ansted became a boom town at the center of deep mining. But by the 1960s the unemployment rate was around 25% and the town shrank. Its current population is about 1,500.

Mayor “Pete” Hobbs remembers the boom and bust times, and like many people in the 1960’s, he had to leave the state to find work. He spent 37 years with AT&T, retiring as a general manager, and returned to an area where his wife has relatives. By then his own home town, Smithers, no longer existed. He is determined that Ansted will not suffer that fate.

“When you look at a map, you see a beautiful pristine area between those two rivers,” he says. “And the question is, what it the best use of the property?”

“In my personal opinion, whatever we decide to use that property for, it represents the gateway to the future of town of Ansted and Fayette County.”

(For more by the major and other area residents, see links at www.appvoices.org).

Tourism could be the long range economic engine for the area, Hobbs and others hope. To promote it, they have helped create a hiking trail from the town to Hawks Nest Park on the New River, 13 miles to the South. The same trail could be extended to the Gauley whitewater area another 20 miles north, Hobbs hopes. But there won’t be much point in a new trail if the mountains are flattened.

Prayers interrupted

Father Roy Crist, an Episcopal priest, supervises three churches but still finds time to serve as president of the Ansted Historic Preservation Council.

The most important thing to preserve now is the mountain, he says. “If they mine that entire (Gauley area), we’re looking at a huge sore spot right in the middle of the most visited site in West Virginia, he said. “God did not give us this land to destroy but he gave us this land to take care of, and we’re not doing a very god job of that. “

The mining operation actually started without a clean water permit,” he said. “There was a hearing at Hawks Nest last September, and we spoke against granting the permit. The DEP (Department of Environmental Protection) paid no attention and issued permit anyway, even though the company started mining without it.”

One protest tactic has been to hold prayer meetings, similar to those held during the Civil Rights movement. The first took place without incident in November 2007.

In April 2008, fifty people gathered for a second Blessing of the Mountains. The group was stopped by a blockade halfway up the mountain. As the service began at the roadside, a group of twenty or thirty miners in pickup trucks, wearing blue company shirts came roaring down the road and stopped at the service and began yelling and screaming.

“There was a lot of taunting and razzing when we were trying to do the service,” he said. “They kept interrupting with things like ‘turn your lights off’ or ‘it’s all about jobs.’ “ During the sermon, one of the miners began shouting a few inches away from the minister’s face, yelling that he was lying, that coal companies don’t mess up the mountains, that they put the dirt back when they are through.

“After service was over, a lot of our group went around and talked with coal miners,” Crist said. “I told them I was glad they were there to worship with us. I wasn’t frightened,” he said.

Hoffman said she was afraid of the miners. “It’s insane – I can’t believe it’s happening here,” she said.

Nature reclaims all

Jeff Proctor, managing director of Class Six Whitewater, is living the dream. He and friends from Ohio established the company in Lansing, WV 35 years ago. “A great day at the office,” he says, “is (in) the Lower New or Lower Gauley at 6 – 12,000 cubic feet per second.”

Proctor has been watching the river every day for decades. “There’s nothing any different than what we have seen in past 30 years,” he said. “Do we see turbidity (after rain)? You bet. I know they’ve been mining. But a logging job can probably cause as much of a problem, and they are probably not as regulated as a mining company.”

Like many others who make their living taking rafters onto whitewater, Proctor sympathizes with environmental concerns. “I understand that Ansted is concerned about coal trucks and traffic,” he said. “And it’s crazy to say there’s not some sort of impact.”

But will that affect the whitewater business over the long run? “This canyon has had its fair share of abuse,” he notes. “If you look at photos of what this place looked like at the turn of the century, it was just stripped for all the timber to help prop up the mines.” But today it looks like a rain forest, he said.

“We are fortunate. Mother Nature has done a phenomenal job of reclaiming the river.”

Gene Clair, a Park Service geologist, also says he is not worried about the impact of mining on the rivers. The law requires mines to stay at least 300 feet from the park boundaries, he notes.

Although acknowledging that there was at least one spill on Peters Creek in 2001, and a number of permit violations on Rich Creek, he believes they were minor incidents. “They’ve been operating pretty good in past,” he said.

He also notes that Powellton is “armoring” channels to reintroduce the trout in Rich Creek, below the mining operations. So far there is no word on the success of the program.

Extending the park

Perhaps the best hope for protecting the New and Gauley Rivers would be to make the National park areas bigger. Congressman Nick Rahall of West wants to do just that.

“The legacy is not complete,” Rahall said in April 2008. “I believe that serious consideration should be given to extending the park boundaries of the New and Gauley to their confluence with the Kanawha River… There are other areas along the New where boundary adjustments are in order, so that we can maintain the integrity of that with which God has blessed us here in New River Country.”

As chairman of the powerful House Committee on Natural Resources, Rahall certainly has the clout to make it happen. He also has a history of protecting rivers: He sponsored a bill in 1978 establishing the New River Gorge as a national park. In 1988, he sponsored a bill to make the Gauley a National Recreation area. And in recent years he has been honored with the National Parks Conservation Association award.

The problem, as always, is with the details. It is possible that a semi-protected arrangement will be proposed. But if the protection does not slow or stop the surface mining, thousands of acres of Gauley Mountain will be leveled, and the runoff and toxic waste problems could affect tourism in the end.

Powellton Coal Co. Violations of Environmental Law On Gauley Mountain

Aug 24, 2007 – Started operations without a permit

Aug. 28 2007 – Failed to properly notify public of blasting operations.

Aug 28 2007 – Started suface mining operations in parts of Rich Creek without certifying sediment control

Aug 28, 2007 – Failed to certify access before hauling coal

Sept. 12, 2007 – Failed to submit surveys, waivers or affidavits for each dwelling …. Prior to any blasting.

Hawksnest Tunnel: The First Gauley Disaster

Seventy five years ago, the area where the Gauley River and the New Rivers meet became known as the site of America’s worst industrial tragedy.

The same water power that today attracts recreational enthusiasts from over the world was, at the time, attracting the attention of hydroelectric engineers. They built a massive tunnel that channeled water from the New into the Gualey to generate over 100 megawatts of electricity between 1928 and 1932.

By 1933, news of some kind of disaster was beginning to emerge. Hundreds of men – now estimated at 476, most of them African American — died simply because they were not given protective gear. Most of the victims were buried in common, unmarked graves. Thousands more were permanently injured, unable to walk home to other states, giving Hawks Nest, WV, the appearance of a “town of the living dead,” according to a 1936 magazine article.

The men were killed by silicosis, an “occupational disease” that occurs when workers breathe fine particles of glassy sand that cuts through lung tissues with steady and predictable effect.

The deaths and injuries could have been prevented had the company issued dust masks and used “wet” drilling methods. But wet drilling might have diluted the value of Gauley Mountain’s pure silica that was in the tunnel’s path.

Dust masks were not used because, the company claimed, they did not know about silicosis. Even so, white engineers who took rock samples in the tunnels were using dust masks. Apparently, the lives of African Americans were hardly thought to be worth the cost of the masks.

The racism, arrogance and cruelty was so astonishing, even in the 1930s, that a full scale Congressional investigation was set in motion.

The investigation uncovered heartbreaking stories about whole families wiped out by silicosis, wives having to file suits just to get their husband’s bodies, and parents searching the Hawks Nest workers camps for their missing sons.

The investigation also uncovered a horrific pattern of secret cemeteries, subversion of the law and threats to witnesses by Union Carbide and its contractors.

It concluded that the tunnel project had been carried out “with grave and inhuman disregard for the health, lives and future of the employees.” The committee placed

the blame squarely on the shoulders of the company: The negligence “was either

willful or the result of inexcusable and indefensible ignorance.”

In the end, none of the company officials went to jail. A few families of the victims received settlement checks for a few hundred dollars at most. But most significantly, the laws regarding occupational disease and labor safety were rewritten during the New Deal era with the Hawks Nest incident in mind.

The incident became even more famous when poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote “The Book of the Dead” in 1938 and included many of the documents from the Congressional committee.

Aside from that book, the companies successfully suppressed information about the incident. Even a novel called Hawks Nest by Hubert Skidmore was pulled out of print by the publisher, and Skidmore himself died in a mysterious fire.

As late as the 1970s, historians said they were receiving death threats and facing legal action for trying to uncover the truth about the incident. To this day, many of the grave sites have not been found.

Physician Martin Cherniak was the first historian publish a book on the Gauley disaster. Cherniak said he struggled to maintain his objectivity while writing The Hawks Nest Incident: America’s Worst Industrial Disaster. Ironically, it was published only a few years after Union Carbide’s disaster at Bhopal, India, where 10,000 people died from a cyanide leak at a chemical plant on Dec. 3, 1984.

In 2008, historian Patricia Spangler published The Hawks Nest Tunnel: An Unabridged History. Along with a summary of events, Spangler published hundreds of full original documents surrounding the incident. This valuable work allows us to objectively analyze the disaster while, at the same time, sense the outrage and horror behind the witness testimony and committee reports of the first Gauley disaster 75 years ago.

Today, the tunnel from the New River to the Gauley still generates 107 megawatts of electricity, like it did 75 years ago. Since it uses a public resource, the project was originally to revert in ownership back to the state of WV in the 1980s. However, the state exchanged it for land that was not worth a fraction of the value of the Hawks Nest electrical complex. And the tunnel itself, as a point of fact, was never worth the lives it cost.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Photos by Michael Sawyer (3, 4, 5, 6) and Jeff Macklin (1, 2, 7)

For more information:

Hawks Nest Tunnel: An Unabridged History, by Patricia Spangler. Available for $22.95 (pluse $5 shipping) from the West Virginia Book Co. http://www.wvbookco.com/ 125 Central Avenue, Charleston WV 25302

Martin Cherniak, The Hawk’s Nest Incident, Yale University press, 1987.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment