Battling for Black Lung Benefits

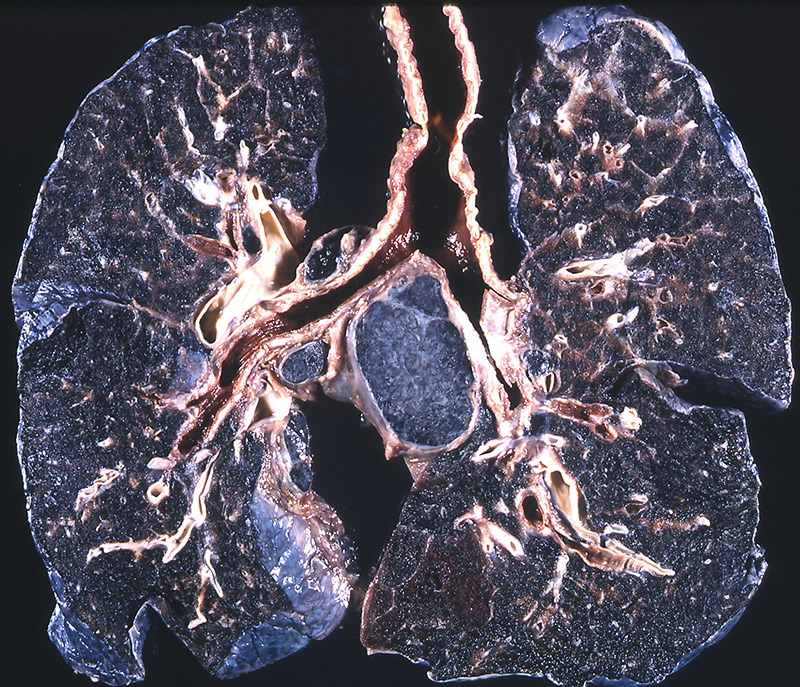

Lungs removed from a patient with complicated black lung disease. Photo by Yale Rosen, CC BY-SA

As black lung disease progresses, the coal miner begins to notice more and more shortness of breath until simple tasks like the walk from the car to the front door leaves them winded.

“That is such a scary feeling when you can’t catch a breath, and you realize that you’re going to die if you can’t catch a breath — but you still can’t,” says Deborah Wills, who has worked as a black lung benefits counselor at Valley Health Systems in West Virginia for more than 29 years.

Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, commonly known as black lung disease, is a fatal, incurable condition caused by long-term exposure to coal and silica dust in and around coal mines. As the dust accumulates, lung tissue becomes inflamed and scarred. Over time this can develop into progressive massive fibrosis, or complicated black lung disease, which causes heavy scarring in the lungs that leads to difficulty breathing.

“Pretty much everybody in the community knows somebody with black lung or somebody that has died from black lung,” says Wills, whose grandfather and great-uncle died from the disease.

The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that black lung has killed more than 76,000 people since 1968. The number is almost certainly higher, as miners have historically had a difficult time getting properly diagnosed, in part due to coal company pressure.

Ed Rich, the grandfather of Big Stone Gap Councilman Tyler Hughes, in a Southwest Virginia coal mine around 1986. Rich is now retired and living with black lung disease. Photo courtesy of Ed Rich

Treatment for the disease is costly. Aside from frequent doctor visits, some coal miners require lung transplants that can exceed $1 million. While some states like Kentucky offer workers compensation for people with black lung, federal law stipulates that the last coal company that employed the coal miner for at least one year is responsible for paying benefits. These federal benefits currently consist of full medical coverage related to the disease and a monthly stipend of $660.10, which can be increased to a maximum of $1,320.10 if the individual has three or more dependents. But if the company is unable to pay, usually due to bankruptcy, then benefits are obtained through the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, a federal healthcare and disabled-worker fund set up in 1977.

An Adversarial Process

For those who apply to receive black lung benefits, Evan Smith, a staff attorney with the nonprofit law firm Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, says that the process “often ends up taking a decade or more” — and that it’s a “very adversarial process.”

Filing the initial claim with the U.S. Department of Labor takes about a year, during which the individual visits an agency-approved doctor and the coal company can submit evidence to challenge the claim. After that, either side can ask for a hearing before a judge, which Smith says takes between two and four years.

“It’s not uncommon to ask a judge to review it and then not even hear from a judge for two and a half years,” he says, adding that there’s a huge backlog of cases.

After the judge’s decision, however, there is often a series of appeals. “And anytime some of the appeals judges find a problem, it’s kind of like chutes and ladders,” he says. “You take a slide back down and go to an earlier step in the process, and then things move forward.”

“As long as these cases are in active litigation, then the coal companies and insurance companies do not have to pay,” he adds. “And so if you’re a coal company or an insurance company, then a rational strategy is essentially to drag out the process for as long as you can.”

Smith states that the companies will often file appeals even when they know they won’t succeed.

“Each time you ask for more review, you don’t have to pay the bill,” he says. “I can only think of a few cases that I’ve been involved with where there hasn’t been a request for at least a judge to get involved.”

More than $45 billion in federal compensation has been allocated to current and former coal miners and their surviving dependents through the fund. Coal companies are currently taxed $1.10 for every ton of underground coal mined and 55 cents for every ton of surface coal mined to finance the fund.

But in 2019, those rates are scheduled to drop to 50 cents per ton and 25 cents per ton, respectively. The fund is already approximately $4.3 billion in debt, according to a May 2018 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. If the excise tax is reduced, the office estimates the debt will exceed $15 billion by 2050.

“Without any congressional action, the trust fund’s debt is going to be far worse than it’s ever been in the past,” says Evan Smith, a staff attorney with the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, a nonprofit law firm. Smith notes that while this wouldn’t immediately affect coal miners and their families, it could have dire consequences in the near future.

Once the debt reaches “a scary-type level,” he says, then legislators from non-coal states “start saying ‘wait a minute, here’s a government program that’s bleeding out money every year; we’ve got to do something about this.’”

According to the Government Accountability Office report, raising the tax on coal companies by 25 percent would eliminate the fund’s debt by 2050.

“That’s the right thing to do, especially if we’re uncertain of how much coal production we’re going to have in the year 2050,” Smith says. “We should do everything we can to have the coal industry more or less pay its bill.”

Resolutions Passed

Big Stone Gap, Va., Councilman Tyler Hughes asks the town council of Pennington Gap, Va., to pass a similar resolution supporting the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. Photo by Gabby Gillespie

“It’s not only a moral issue that a company takes care of its workers, but it’s also an economic issue,” says Big Stone Gap Councilman Tyler Hughes, whose grandfather suffers from black lung. “We live in a really impoverished portion of the commonwealth; and most people, regardless of where they live, have trouble paying for their healthcare whether they have black lung or not.”

The towns of Pennington Gap, Va., Dungannon, Va., Haysi, Va., and Benham, Ky., have since passed similar resolutions in support of keeping the excise tax at its current level.

“We are happy to see Big Stone Gap to be the first to step out on that,” says Pennington Gap Councilwoman Jill Carson. “[Cutting the excise tax] would just be so devastating for those families in what is already a poor, poor part of the country.”

Big Stone Gap councilman Tyler Hughes, Peggy Brock from the SWVA chapter of the Black Lung Association and Bethel Brock, president of the SWVA chapter of the Black Lung Association and a former miner living with complicated black lung disease, met with Senator Mark Warner (second from right) to hand-deliver four local resolutions of support for extending the black lung excise tax. The meetings was one of about 40 that residents of Central Appalachia had on Capitol Hill in late September. Residents of Southwest Virginia also delivered the resolutions to Rep. Morgan Griffith. Sen. Warner is backing legislation that would require the government to look into why coal miner participation in black lung screenings is only 35 percent. Photo courtesy of Sen. Warner’s staff

In late September, Hughes and nearly 40 representatives from The Alliance for Appalachia — a coalition of grassroots organizations including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper — traveled to Washington, D.C., to urge lawmakers to extend the black lung excise tax. They also pressed legislators to pass the RECLAIM Act, a bill that would accelerate the release of $1 billion in existing funds to clean up abandoned mine lands.

National Mining Association President Hal Quinn, however, argues that keeping the trust fund tax at its current rate would burden the industry. “Changing the schedule now would effectively impose a tax increase on an industry struggling to recover from the regulatory excesses of the past administration,” Quinn wrote in a June 2018 letter to two key U.S. House members, according to Reuters.

But Evan Smith states that the industry has offered no economic evidence to support that.

“The bottom line is that the [coal] market has week-to-week fluctuations that are greater than the tax that we’re talking about. … And so to ask those producers to pay just an extra 60 cents of that I think is a very modest cost to make sure that coal miners are taken care of,” Smith says. “Industry lobbyists are always going to say that anything that imposes a cost is a cost that they cannot bear. That’s what they get paid to say.”

Black Lung’s Resurgence

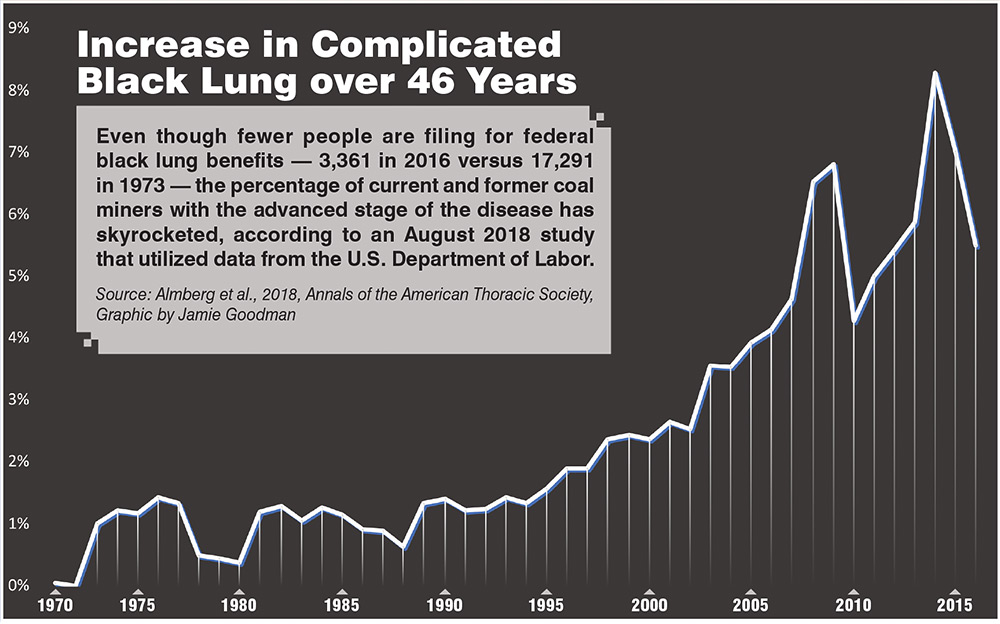

According to Reuters, Hal Quinn’s letter stated that black lung disease was in decline. But according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, black lung diagnoses have steadily climbed after a low point in the ‘90s.

Progressive massive fibrosis, or complicated black lung disease, has also grown, according to an August study. In 2014, 8.3 percent of miners filing for black lung benefits had the advanced stage of the disease, compared to 0.6 percent in 1988. And 84 percent of miners with progressive massive fibrosis most recently mined coal in Central Appalachia.

Beverly May is a retired nurse practitioner in Eastern Kentucky who treated patients with black lung, and is currently working toward a doctorate in public health.

According to May, the recent rise of black lung disease can be partly attributed to thinner seams of coal. Since many of Central Appalachia’s coal-rich seams have been depleted, miners must cut through more rock than before to reach thinner seams of coal — which creates a much greater volume of dust. A 2012 joint investigation by National Public Radio and the Center for Public Integrity discovered that about 52 percent of mine dust samples between 1987 and 2012 showed dangerous levels of silica.

Dust monitors such as these are meant to warn miners of unsafe coal and silica dust levels. Photos courtesy of U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration

“Worst of all, there was extensive tampering with the mechanisms for monitoring the dust,” says May. “What the miners said is that on a routine basis, after there were no more unions, they would get to work, they would do three or four cuts with the continuous miner [machine], and then the supervisor would come and take the personal dust monitor from them and then hang those dust monitors up in the air intake. And then they would proceed to make another 11 or 12 cuts with the continuous miner. So only a small portion of the dust that the miners were actually breathing during the course of that shift was represented in the personal dust monitors that were turned into [the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration].”

In July, eight former employees of the now-bankrupt Armstrong Coal Company in western Kentucky were federally charged with submitting forged dust monitoring results to the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration. All eight pleaded not guilty, and trial is set for June 19, 2019, according to WEVV-TV. Each faces five years in federal prison and a $250,000 fine.

To Deborah Wills with Valley Health Services, black lung is “a totally preventable disease.”

“Miners don’t have to die from black lung. If coal operators had appropriate ventilation systems in the mines and everyone went by the rules, there would be no black lung disease,” she says. “If people would worry more about workers’ health than production, we wouldn’t have black lung disease.”

Sign The Alliance For Appalachia’s petition asking Congress to protect the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund at blacklungkills.org.

Kentucky Law Makes it Harder to Get Black Lung Benefits

Current and former Kentucky coal miners now have far fewer options when it comes to finding a doctor to prove they have black lung disease so that they can access state workers compensation, which is separate from federal black lung healthcare.

Before a state law took effect in July 2018, miners could visit one of the 10 radiologists and pulmonologists in the state who are currently federally licensed “B readers” — those trained to identify black lung from a chest x-ray. Now, miners can visit only the five pulmonologists to confirm their black lung diagnosis and receive state benefits.

State Rep. Adam Koenig, the lead sponsor of the legislation, told NPR in April 2018 that he “relied on the expertise of those who understand the issue — the industry, coal companies and attorneys.” However, he also stated that “not everyone who had a specific interest was involved … I’m not sure I was even aware of NIOSH,” referring to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the federal agency that licenses B readers.

Beverly May, a retired nurse practitioner in Eastern Kentucky who has treated people with black lung, noted that Rep. Koenig is from a non-coal producing county.

“There was no reason that he would have had any particular dog in that fight,” May says. “So I can only guess that this was the coal industry going through the legislature for some backdoor protection from this avalanche of black lung claims.”

Dr. James Brandon Crum, a NIOSH-certified radiologist in Pikeville, Ky., is one of those now excluded from diagnosing black lung for state benefits. According to Ohio Valley Resource, Crum is the one who alerted researchers to a disturbing increase in black lung disease, particularly among younger miners.

Evan Smith, a staff attorney with the nonprofit law firm Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, claims that the law specifically targeted Crum.

“I wish [Rep. Koenig] had … just called it ‘The Coal Industry Does Not Like Brandon Crum Bill of 2016,’” Smith says. “That’s what it really comes down to, that there’s a highly trained, highly reliable radiologist in Pike County that’s done more than anyone else to document the resurgence of black lung in our region, and the coal industry cannot find any rational reason to discredit him — so they’re trying to gerrymander the rules so that he can’t be involved in the system.”

Advancing Healthcare in West Virginia

In February, West Virginia State Sen. Richard Ojeda introduced a bill to create the State Black Lung Fund, which would be separate from state workers compensation. The bill, supported by the United Mine Workers of America Local 1440 in Matewan, W.Va., would allow a person who has mined coal in the state for at least 10 years and “has sustained a chronic respiratory disability” to be eligible for benefits.

To pay for the fund, the bill proposes a severance tax on all forms of energy generation. It also directs the governor and state legislature to cooperate with other coal-producing states to recoup a portion of the current federal excise tax on coal.

“Coal miners all across West Virginia are suffering from black lung disease but do not qualify for federal benefits,” wrote Sen. Ojeda in a February Facebook post. “It’s time we give them what they deserve.”

The bill awaits decision in the West Virginia Senate Government Organization Committee.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

4 responses to “Battling for Black Lung Benefits”

-

These Doctor,s that lie about a miner,s diagnoises to protect the coal Co they represent should be procecuted to the full extent of the law. We demand to be treated like human,s. Were not animals to slauter.

-

I think miners that have been diagnosed with the disease should not have to wait and never get benifits , then die the terrible smothering death like my husband who was diagnosed time and time again…but some crooked dr..that works for coal company insurance co. Lies time and time again, and causes the black lung patient to be denied benifits as happened in the case of my husband who passed in july, oxygen on high 06. Breathing treatments often no help, it’s a shame, he never received benifits he was due, all because of a coal co lawyers lying dr…it’s a shame…

-

I look for an increase in the number of miners that will be diagnosed with COPD, Emphysema, Silicosis, and Black Lung that have worked in East Tennessee in the next five to ten years even in those that have never worked in a deep mines. Time will tell. I also believe that there will be a decrease in the number of locals that will be diagnosed with asthma, thyroid problems and cancer to decrease in the next 40 to 50 years. Again time will tell. These miners deserve whatever benefits that can be obtained.

-

I think laws allowing social security disability benefits be reduced because that miner is also receiving black lung benefits should be changed and miners should receive their full entitlement for both even if they are under their retirement age. Laws need to be changed for the coal miner.

Leave a Comment