Community Organizing Amid Destructive Mining

In 2000, Pat Jervis, a high school teacher in Wise County, Va., received notice of the Kelly Branch Surface Mine permit in front of his mother’s home. He appealed to government agencies to challenge Meg Lynn Coal’s permit to mine and began meeting with other community members who were concerned about the impacts of surface mining.

SAMS members Jane Branham and Bill McCabe at Branham’s home in Norton, Va. Photo by Hannah Gillespie

Although the mine’s permits were granted in 2000 and Kelly Branch moved forward, the citizens were still engaged in monitoring environmental threats. In 2007, this group became the Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards, a nonprofit organization whose goals are to stop surface coal mining from destroying their neighborhoods, to improve the quality of life in the area and to help rebuild sustainable communities.

“It started out as just some local citizens trying to protect their property and trying to use the laws to do that,” says Jervis. “Which, at first glance, looked like that was possible. But it’s more political than it is legal, I think. Those were some hard lessons to learn. And I’ve taught civics. You can teach how the law is supposed to work, but as I’ve heard a lot during my lifetime: what is legal isn’t always fair.”

Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards has utilized a variety of tactics, including community organizing, political advocacy, nonviolent direct action and alternative economic projects. This included SAMS members going door-to-door and sharing information with the community.

The community was already aware of the dangers associated with mining due to a local tragedy that occurred in 2004 at a mine owned by Jerry Wharton, who also owned the company behind the Kelly Branch Mine.

“The focal point that convinced people they had to do something was the death of Jeremy Davis who was a three-year-old boy, asleep in a trailer, below … a mountaintop-removal mine,” says Bill McCabe, an environmental justice organizer for the Sierra Club who worked with SAMS and regional mining communities. “An unlicensed bulldozer operator, at 3 o’clock in the morning, pushed a boulder over the mountain and it crashed into a trailer and killed the child in his bed. The regulators didn’t do [anything]. The coal operators denied their liability. And well, the death of a three-year-old has a pretty dramatic effect. That galvanized people.”

Wise County has historically been dominated by coal mining. More than 30 peer-reviewed studies since 2010 show a connection between proximity to mountaintop removal operations and poor health outcomes, including higher rates of cancers, birth defects and heart, lung and kidney disease. Coal mining’s changes to the landscape have affected local residents environmentally, politically and economically.

Many older SAMS members speak about how their home has changed. Larry Bush, a former union coal miner, describes a pond that used to be deep enough for baptisms. “Now it’s filled with silt — runoff from those mines — to where you just can’t. It’s just weeds growing across what was a ten foot deep pond,” he says.

Residents describe other changes in their communities due to mountaintop removal such as the burying of streams and air contamination from coal dust. Private coal companies have also restricted access to areas where residents used to live, walk and hunt. SAMS members have challenged these and other factors since the organization’s inception.

Ison Rock Ridge

“The biggest victory that I can think of right off the top of my head, was saving a mountain!” says Jane Branham, former SAMS president.

In 2007, A&G Coal Corporation — which by then operated the Kelly Branch Mine— proposed a 1,200-acre surface coal mine on Ison Rock Ridge in Wise County, Va. For eight years, SAMS members worked to stop the permit from being issued by organizing and participating in marches, hearings and campaigns and pursuing legal appeals in conjunction with other organizations.

The state initially approved the permit in 2010, but the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency intervened to delay the process because of the company’s water quality violations and related problems at other mines.

Members recall participating in monitoring local water quality, including at the Kelly Branch mine near Jervis’ mother’s home, and campaigning against coal dust while the permit was on hold.

“Matt Hepler [was] our water organizer,” recalls Diana Withen, former SAMS vice president. “He [did] a lot of water testing, and he’s gotten several hits on selenium in the water, and where the coal companies are releasing more than the legal amount into the water.” These and other water pollution violations have led to court cases and settlements, totaling hundreds of thousands in fines.

SAMS member Sam Broach describes the coal dust from trucks traveling to and from other nearby mines. “It was so dusty, you’d go through [a nearby intersection] and everything was just covered with dust,” he says. “People got to where they couldn’t breathe so we went to our congressman, to D.C., and to Richmond. Finally, we got them to put in washers to wash those trucks down, to try to keep the dust from coming out [and] they stopped coming through town, so we got some victories there.”

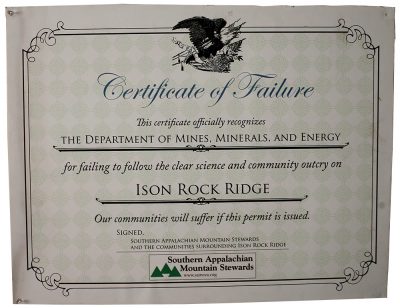

During the fight against the Ison Rock Ridge mine permit, SAMS members delivered this “Certificate of Failure,” above, to the Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy. A reprint now hangs proudly in the SAMS office. Photo by Hannah Gillespie.

The Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy denied the Ison Rock Ridge permit application in 2013 after A&G failed to address the EPA’s concerns and keep their application current. A&G then started appealing that process and SAMS intervened. The process of appeals finally ended in a win for SAMS in 2015.

The victory is a source of pride for many SAMS members, though Ison Rock Ridge is not permanently protected. Since oil and gas company Penn Virginia Corporation owns the land, A&G or another mining company could lease the land and re-apply for the permit.

“Ison Rock Ridge sits in between five communities including the town of Appalachia and four historical coal camps around Appalachia,” Branham says. “If that mountain had been blasted away it would have devastated all those communities and those communities knew it.”

Branham describes SAMS members knocking on doors and making phone calls to connect with others in the community. Even in an area “dominated by the mono-economy system here … almost everybody was like thank you, thank you for helping us, thank you for being our voice,” she says.

Moving forward

“Wise County used to be one of the biggest apple producers in the nation, before strip mines came in,” says Withen. “But when they blew up the mountains, they blew up the apple orchards, so we have two apple orchards now left in our county. Wise is [still] the heaviest stripped coal county in Virginia. Twenty-five percent of the land is already blown up. But, there is a lot of potential there still.”

After periods of internal division and moments of uncertainty regarding the livelihood of the organization, SAMS is currently in transition. According to Bill McCabe, as older members’ health worsens, the organization feels an urgency to re-engage past members and document its history before those stories are lost.

SAMS members protest the proposed mine on Ison Rock Ridge in May 2011. Photo courtesy of the Sierra Club

In the midst of this transition, some members have found strength. “SAMS’ biggest asset has been, for a long time and still is, that it’s a family,” says Adam Wells, former SAMS treasurer and current New Economy program manager for Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper. “We love each other. Don’t always agree with each other, but there’s a lot of love there.”

The region is also changing, as the coal industry declines and some foundations shift their funding priorities. Although SAMS was established to combat mountaintop removal, the organization is now addressing other issues.

“Social justice in general is something that we are looking at, with the environment being the number one priority,” says Terran Young, a SAMS board member who is also serving as a Highlander Transition Fellow with SAMS, the community and scholar organization Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network, and Appalachian Voices.

“We’re committed to what’s right and to having people treated equally,” Young continues. “That’s something we’re willing to take on whether or not everybody agrees on it.”

In 2016, SAMS and partners reopened a 1979 study that explored Central Appalachian land ownership and taxation of companies that own mineral rights. With approximately 45 percent of the land in Wise County owned by corporate landholding entities, this study has local significance.

Speaking about how SAMS is keeping their momentum, Young says, “I think the land study will be a big part of it, especially as far as recognition for SAMS, because we are a very small, pure grassroots organization. It was created by the people, and run by the people of this area.”

Azariah Conerly, Ricki Draper and Christian Huerta contributed to this report. The authors are Appalachian State University students and members of the university’s Scholar Activist Alliance, a group that links academic institutions and frontline community organizations. They began interviewing current and former SAMS members in 2016 to document the organization’s history.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment