Restoring the Brook Trout

At the dawn of American Civilization, the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) could be found virtually anywhere in the Appalachians where cold water flowed.

The brook trout is the most fragile of the East’s gamefish and it serves as an indicator species for a watershed. Deforestation caused by logging and chestnut blight in the late 18th and 19th centuries dealt the fish a deadly blow from which it has never recovered and now other factors, such as poor land-use practices and acidic water further compound the fish’s woes.

For years, anyone with a soft spot for the beautiful fish, with its brilliant green, red and yellow markings, was aware that the fish is hanging by the skin of its gills to maintain a foothold in the Appalachians most remote coldwater streams.

How bad it suffers as a species, however, was a mystery until recently, when the Eastern Brook Trout Venture release its findings from the most comprehensive study ever performed on brook trout.

The venture brings together a who’s who of agencies and conservation organizations. Participating are: Fish and Wildlife Agencies from 17 states and conservation organizations, including: The Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, Trout Unlimited, The Izaak Walton League of America, Trust for Public Land and the Nature Conservancy as well as academic institutions, including the Conservation Management Institute at Virginia Tech and James Madison University.

The venture had little good news to report with its historic study. It found that intact populations of brook trout can be found in only about five percent of the fish’s historic habitat.

There is one commonality from Maine to Georgia: the fish survives almost exclusively in fragmented populations in the extreme headwaters of watersheds.

The fish has suffered most in the southern portions of its range, especially in Georgia and South Carolina. In fact, no intact populations survive in those states and the fish had been extirpated from half of its historic habitat, the study found.

One major problem has been competition from non-native rainbow trout, past forestry practices and poor land management. The same can be said for North Carolina and Tennessee, which can boast only one intact subwatershed, which is located on the Tennessee side of the state line.

The problems throughout the Southeast all begin with poor land management of generations past. As forests were clearcut throughout the region a century ago, streams were robbed of a vegetative canopy and water temperatures rised. To restore trout fishing, the non-native rainbow trout was introduced.

As habitat improved, it was the rainbow, not the native brookie, that extended its range. The rainbow trout has hampered brook trout populations in the Southeast more than any problem the fish faces and have affected 69 percent of subwatersheds.

The highest-quality habitat south of Virginia is found in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Nantahala National Forest. Protection of these and other fragmented populations will ensure the survival of the species in the region, the study found.

Virginia’s brook trout are somewhat better off. Only about nine percent of Virginia’s populations remain intact and the fish has been extirpated from 38 percent of its historic subwatersheds.

According to the study, the Old Dominion has the strongest brook trout populations south of the Mason-Dixon Line and the George Washington and Jefferson national forests and the Shenandoah National Park protect many healthy populations. The amount of brook trout habitat the state has lost, however, comprises an area the size of Connecticut. Those areas have been degraded by a variety of problems, including poor land management, agriculture, both of which has contributed to a rise in water temperature, the state’s greatest threat to its native trout.

Faring worse in some respects is West Virginia, which still supports brook trout in a majority of the historic range, but in reduced numbers. Only four intact watersheds remain, but the fish has only been extirpated from six percent of its known range.

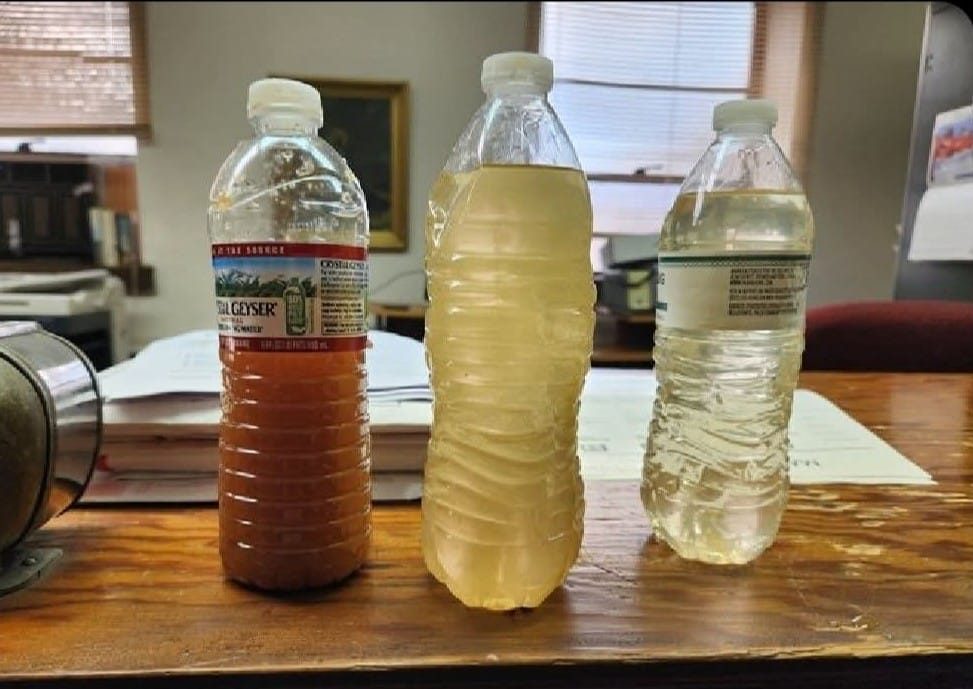

The study lists poor land management as the Mountain State’s greatest threat to trout, with forestry problems affecting half of the brook trout subwatersheds, acid deposition affecting nearly a third and active mining harming 17 percent.

With brook trout at least present in most of its watersheds, the study found that expanding West Virginia’s successful lime-dosing projects (to raise stream pH) and restore aquatic life could make hundreds of miles of rivers habitable for brook trout.

Our collective challenge is to protect the best remaining habitat and restore the rest,” he said. Lee Orr, brook-trout coordinator for Trout Unlimited’s West Virginia

Council, said it’s time to also scale up habitat-improvement programs.

“Brookies are quick to respond to habitat improvements,” Orr said.

The study found fishing pressure to be the least of the trout’s problems from Maine to Georgia. Urbanization, however, has threatened streams all along the mountain chain.

The venture’s partners hope to use the information to develop conservation strategies for state and federal agencies to restore the fish. The venture also plans to collect additional data, promote policies geared for the brook trout and carry out watershed-improvement projects in hopes of restoring this wonderful, fragile resource.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment