Mountian Justice Summer

Documentary cameras rolled as heart-wrenching stories met a steely resolve to organize and stop mountaintop removal mining.

Several hundred participants met at this year’s Healing Mountains conference in West Virginia, organized by the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, Heartwood, the

Coal River Mountain Watch, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth and dozens of other organizations.

Keynote speakers Dorris “Granny D” Haddock and former Congressman Ken Heckler challenged participants to organize.

“Can the planet be saved … despite those who insist on staying the course of destruction because it profits them?” Granny D asked. “You will see the outcome in your lifetime.”

One problem, she said, is that “there are more Washington lobbyists than tree frogs – and with stickier fingers.”

Heckler noted that mountaintop removal “is in essence war on the environment.” And he noted that by externalizing the costs of coal mining through mountaintop removal, all mining had been made more dangerous.

“In order to compete with operators of mountaintop removal mines, [the deep mine owners] have to cut costs,” Heckler said. “They use foam instead of proper seals. If you abolished mountaintop removal, you’d have safer mines.”

Many other speakers talked about the problems mountaintop removal had caused for them.

“Somebody asked me,” said Patty Sedok, “if we had any endangered specied in our area. I said, you’re looking at one.” She compared mountaintop removal to a kind of genocide. “Just because we’re not dropping dead on the spot, people think we shouldn’t use that word. But our water supply is being poisoned and our air is being poisoned… They’ve tried to blast us, dust us, poison us and blow us up. Now they are trying to bribe us. They say if you move away we’ll pay for your kids college education. But you can never move back, and neither can your children.

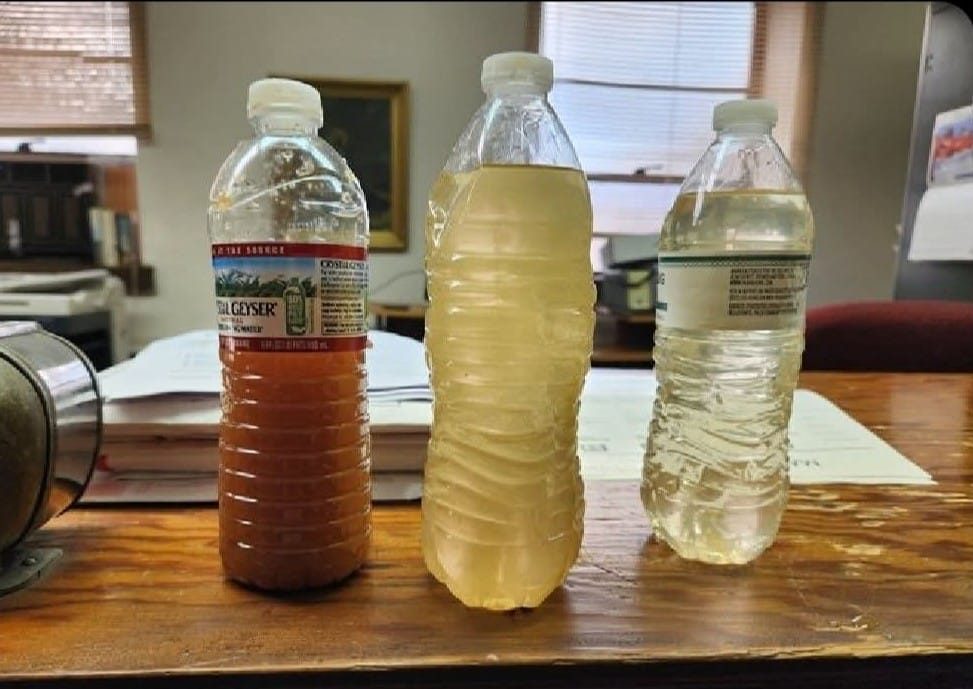

Donetta Blankenship, a resident of Rawl, West Virginia, has experienced liver failure, osteoperosis, and many other physical problems, allegedly from toxic chemicals being injected into the aquifer.

“I myself am dying,” she told the crowd. “It could only be the water.”

Pointing to a map and describing the destruction of the mountains behind her home, Maria Gunnoe said: “These tears are not of sadness, they are tears of rage for what they did to my home, to my culture. This is the land where my daddy was laid. How can they do this to us? This is my back yard. When is it going to be yours?”

As if the long term heath effects were not enough, others are worried about devastating flooding from weak sludge dams.

“I fear there will be a disaster,” said mine safety expert Jack Spadaro, who noted that there are 225 slury impoundments sitting on top of old mine workings. “There aren’t any mines that are operating legally in the sense of operating fully within the law,” he said.

One of the worst prospects for disaster is the Marsh Fork Elementary School. A new initiative to begin building a new school, called Pennies of Promise, was announced by Ed Wiley at the conference.

What can people do? For one thing, according to Coal River Mountain Watch’s Judy Bonds: “Don’t let anyone get away with saying “clean coal.” It doesn’t exist.”

For another, according to Lenny Kohm, there is a need to support the federal Clean Water Protection Act. “They’re blowing up our mountains and there ought to be a law against it,” Kohm said. “There. I just told you our whole plan.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment