An Indigenous-led initiative seeks to reintroduce bison to the region on a reclaimed mountaintop removal coal mine in Eastern Kentucky

Many people believe wild bison have only ever lived and roamed in Yellowstone National Park or the vast open spaces depicted in Western films. Yet, Indigenous and archaeological records indicate that bison were found in nearly every state of what is now the United States — sorry, Hawaii — including in Appalachia.

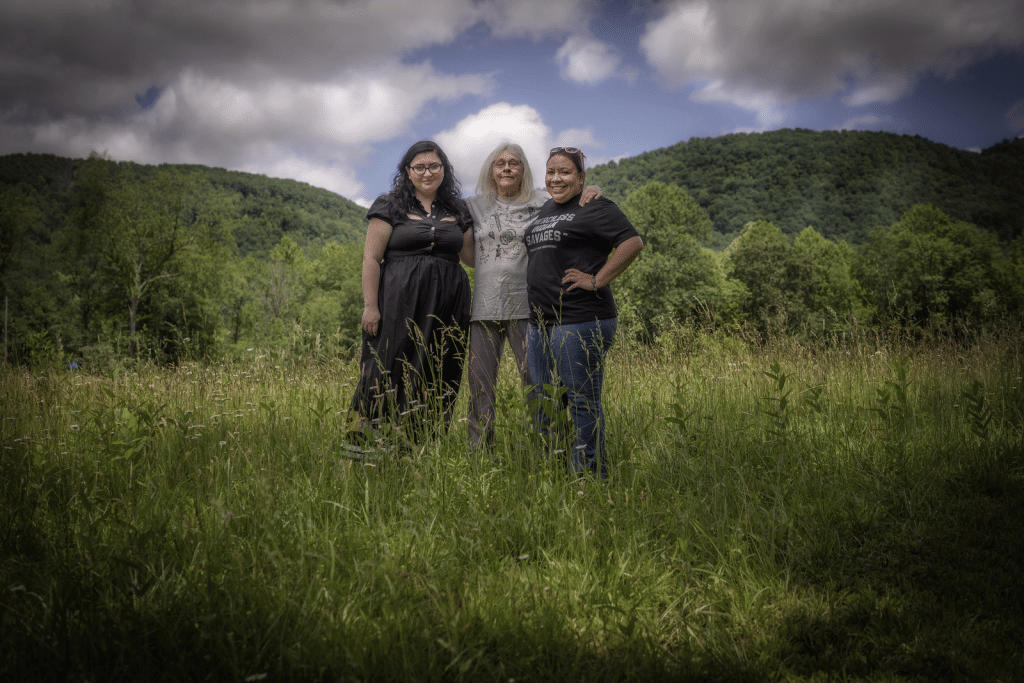

In Letcher County, Kentucky, the Appalachian Rekindling Project, an Indigenous, women-led organization, is seeking to reintroduce bison to the region on 63 acres of a reclaimed mountaintop removal coal mine.

“Eastern Kentucky is a place where bison were native to, but they were removed at the same time that many of our people were removed, and it did upset the ecosystem,” says Tiffany Pyette, a Cherokee descendant and founder and co-executive director of ARP, during a January webinar.

The group’s goal is to reintroduce four bison on the property this summer, along with restoring native grasses, such as big bluestem, for them to eat.

“Their survival here creates survival for so many other species, including us,” continues Pyette. “And so it’s really, really important that we bring them back. We’re bringing them back for a lot of reasons, but mostly because the land needs them.”

Did bison live in Appalachia?

“Bison are an animal that can adapt to both living on the prairies and grasslands, but they also live in other ecosystems as well,” says Rosalyn LaPier, an award-winning Indigenous writer, environmental historian, ethnobotanist and professor. “But they eat grass, so they primarily have to live in places where there’s grass that they can eat.”

When people talk about bison, they usually are referring to the Plains bison, known by its repetitive scientific name Bison bison bison, according to LaPier. It is one of two subspecies of American bison currently found on the continent. The other subspecies, Wood bison, or Bison bison athabasca, is native to the northwest portion of the continent, including Western Canada, Alaska and First Nations lands.

“As westward expansion was happening, that is when we saw bison really kind of retreat to the Great Plains,” says LaPier.

Overharvesting, territory loss and habitat changes from increased farming — all attributed to European settlers — led to the species’ decline overall and eradication from the wild in the Eastern U.S.

‘Rekindling’ Appalachia’s relationship with bison through Indigenous land management

The disappearance of bison from Appalachia and overall species decline over the centuries is inextricably tied to the forced removal and cultural and physical genocide of Indigenous people in the U.S.

“Indigenous communities today are working to rebuild and working to revitalize some of their cultural practices from the past and religious practices,” LaPier says, adding that this involves their relationship to the natural world, including bison.

A common misconception or stereotype is that Indigenous populations only lived in the natural world as it existed. However, they played an active role in shaping their environment.

“When European settlement first came to the East Coast, what they were viewing was not sort of this ‘Garden of Eden,’ as was often described, but a place that was really managed by Indigenous peoples,” LaPier says, providing examples like controlled burns and plant transplantation.

To ensure that certain animals would flourish, Native people would practice habitat enrichment, such as maximizing the types of grasses that animals like bison would eat, LaPier explains.

“They don’t have to ‘go on the hunt or go chase bison down,’” they say. “They know exactly where they’re going to be because they’ve created pastures for them to go and eat.”

Some Tribal nations in the Great Plains have been working to revitalize their relationship with bison since the 1990s, LaPier explains, and their experience can provide direction for those beginning this work.

“As [Indigenous groups are] rebuilding and kind of revitalizing those relationships, I think they can look to other tribes who have been doing this now for a while and have been doing it successfully,” LaPier says.

Pyette and her ARP co-executive director, Taysha DeVaughan, have been learning from other bison programs, visiting herds on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming and The Nature Conservancy’s Nachusa Grasslands in Illinois. But ARP’s project on a former mountaintop-removal site is fairly unique. Some of the best comparable data to support their efforts is found in the Țarcu Mountains of Romania.

In 2014, Rewilding Europe and World Wildlife Fund Romania launched an initiative to reintroduce European bison, or Bison bonasus, to the mountainous region. A 2024 study found that the herd of 170 bison could capture 54,000 tons of carbon per year, equating to the removal of an estimated 84,000 average gas-powered vehicles.

“It’s one thing to say,’ I know [this will work] because my family and the people that I look up to in my community say that bison would be a good fit,’” Pyette says. “It’s another thing to be able to say … when they reintroduced them to Romania again, this is what happened — and this is how much better that forest did afterward.”

Bison as ecosystem engineers

Pyette refers to bison as “ecosystem engineers” that offer numerous benefits to the land, from their hooves that help till the soil to their fur that stores seeds, which are dispersed to the land.

The reintroduction of bison to Appalachia, especially on former mine land, should be approached holistically, LaPier emphasizes. This work includes considering how Indigenous populations maximized the habitat so that bison could thrive.

“It’s not just, ‘Let’s put some bison on a sterile piece of land that’s been disturbed, and wonderful things will happen,’” LaPier says.

ARP’s herd will rotationally graze, and the organization will plant native grasses and plants for both the animals and ecological improvements to the land. Some include aronia, persimmon, plum, Kentucky coffee tree, spicebush, bundleflower, false indigo, hazel and senna. Their diet will be supplemented with hay, which will be grown on another property APR owns in Virginia.

After testing the property’s water and plants, ARP determined that while the plants are safe for consumption, the water is not — it contains high levels of aluminum. For the first three years, ARP will truck in clean water for the bison, while the team works to create healthier water conditions on the property.

“We want them to be as wild as possible,” Pyette says.

Recently, ARP met its fundraising goal of $60,000 to build a fence around its property. The fence is less about keeping the bison in and more about keeping people off the property to protect the animals.

“They’re not that interested in leaving if they have everything they need,” Pyette says. “Now, if they don’t have what they need, they will leave to go find it.”

They are starting with only four bison because of their small land mass compared to the wide-open spaces out west.

“Ideally, for one bison, you should have about 20 acres,” Pyette says. “So, with our 63 [acres], we’re pushing it.”

As the bison breed and the herd grows naturally, Pyette hopes to share bison with other Indigenous-led organizations looking to reintroduce bison in the future.

‘The land deserves better’

Not so coincidentally, ARP’s property falls within the designated boundaries of the proposed construction site for a 1,408-bed federal prison. The organization acquired the land with support from the grassroots coalition Building Community Not Prisons.

“We have other plans for this land, because our community deserves better, the land deserves better, and we have Indigenous knowledge on how to fix what was wrong,” Pyette shared on a January 2026 webinar.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons still intends to move forward with the proposed prison, and U.S. Rep. Harold “Hal” Rogers of Kentucky recently applauded the inclusion of $610 million for construction funding in the 2026 federal funding package. But, Pyette points out, the agency won’t be able to build using its original blueprint because of ARP’s property — and she won’t sell. To date, ARP hasn’t been approached about selling the land.

Their bison herd won’t offer as many jobs as a federal prison, according to Pyette. But their goal is to create opportunities for the community and the greater economy of Eastern Kentucky.

“We want Appalachian artisans to be able to spin down [bison] wool and sell it or use it in their projects,” they say. Other ideas include meat sales from cultural harvests or products made from bison, and hunting permits to control the local deer population.

Ultimately, Pyette says, “bison are everything” for Indigenous populations and “truly a sacred animal.” Reintroducing bison to their homelands and being able to be around them once again feels powerful.

“It’s deeply healing not to imagine what times were like — our ancestors’ relationship with them — but to see it,” Pyette says. “That’s incredibly healing.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment