Clearing the Air on How Wood Pellet Factories Affect Their Neighbors and the Climate

By Noah Vickers

Wood pellet manufacturers have been purchasing forested land and building processing plants since 2010, causing air quality, water quality and forestry issues in low-income communities across southern states.

In recent years, wood pellet production has increased in the U.S. to fulfill usage demands in European countries. Wood pellets come from processed raw material like lumber, sawdust, wood chips, and mill scrap which is ground up into hamster-food-sized pellets. Wood pellet biomass is a plant-based material used as fuel for heat or energy. While less energy-dense than coal and ethanol, when burned the heat from the pellets can power generators and heaters.

Since its classification as a renewable energy source in Europe in 2009, wood pellets have slowly filled the role of other burnable fuels like coal for some power companies, according to public radio program The World. But while the European Union may consider wood pellets to be a renewable fuel, many scientists and environmental advocates disagree because it takes decades for newly planted forests to replace the carbon-capturing capacity of the forests cut down for biomass.

There are also local environmental concerns. The production of wood pellet biomass creates mass amounts of sawdust that can be harmful to air quality. This has led to local communities seeing health and safety problems.

Sampson County

In 2016, Enviva opened their third processing plant in the South in Sampson County, North Carolina. The plant produces 600,000 metric tons of pellets per year, according to Enviva.

“Here in Sampson County, they’ve installed a few controls, but not enough to control the dust because people are still complaining,” says Ruby Bell, a resident and activist near the Sampson County plant.

When Bell gets close to the plant, her asthma acts up and her eyes get irritated. She ended up having to buy an expensive air purifier for her home five miles from the plant. While this has helped air quality within her home, Bell says that others in her community cannot afford air purifiers and they “should not need one in order to help keep the air clean inside their homes.”

“For people who live extremely close, I feel really bad for them because there is absolutely nothing that they can do,” Bell says. “The lady who indicated that she and her husband said they had to wash [sawdust from] their car. She’s a cancer survivor. She’s still struggling with that. And she said, ‘I can’t even sit outside.’”

Bell says she feels that there is nothing people living close to the plants can do.

The Sampson County plant, like most wood pellet plants, has installed some pollution control devices to reduce emissions of chemicals that can leach into water and hazardous air pollutants like methanol, acrolein, and formaldehyde, according to Southern Environmental Law Center Attorney Heather Hillaker.

Enviva, North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and the environmental group CleanAIRE NC, represented by the Southern Environmental Law Center and Environmental Integrity Project, came to a settlement agreement in 2019. The settlement required installing additional control technologies to Enviva’s plant in Hamlet, North Carolina, to reduce emissions by at least 95%.

Enviva has since acknowledged the need for similar technologies at every new proposed wood pellet plant, according to Hillaker.

In January 2022, North Carolina DEQ granted an air quality permit to Enviva’s Sampson County plant requiring no major changes.

Robeson County

In March, Active Energy Group, an international biomass energy company, sold the site of their planned facility in Robeson County, North Carolina, amid community opposition and legal troubles.

“We started educating folks about really what was going on and the impact to our North Carolina, not just to the North Carolina forest, with the destruction of our forest, but to the community itself, and a lot of the harm that was caused from the impacts of the facility being in those communities,” says Anita Cuningham, an activist and Robeson resident who advocated to prevent the facility’s construction.

Educating the Robeson community on the potential impacts of facility construction was important to Cuningham. She says that Active Energy overlooked air, water, and noise pollution in the permitting process.

Cuningham said she was ecstatic when Southern Environmental Law Center announced Active Energy would not be moving forward with the facility and that she was thrilled to be able to prevent harm to her community.

The population of Robeson County is 23.2% Black and 46.3% American Indian, according to the 2020 U.S. Census. Many of the sites for wood pellet plants are located in Black and Brown communities. As many as 24 wood pellet production sites in the South are in or within four miles of an environmental justice community, according to a study published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Justice.

Cuningham has some advice for others looking to prevent local harm done by wood pellet biomass facilities.

“I think that partnerships and collaborations with other groups that have the same vision in terms of environmental justice, social justice, climate justice, and partnering with those organizations, finding out what resources can be shared — non-financial resources or financial resources — so that everyone can come together,” she says. “Because we know that collectively, our voices are strong, and that the folks that have been going through a lot of different kinds of campaigns stopping these dirty industries here in North Carolina, we know it’s not new, they’re continually doing it as we speak.”

Deforestation

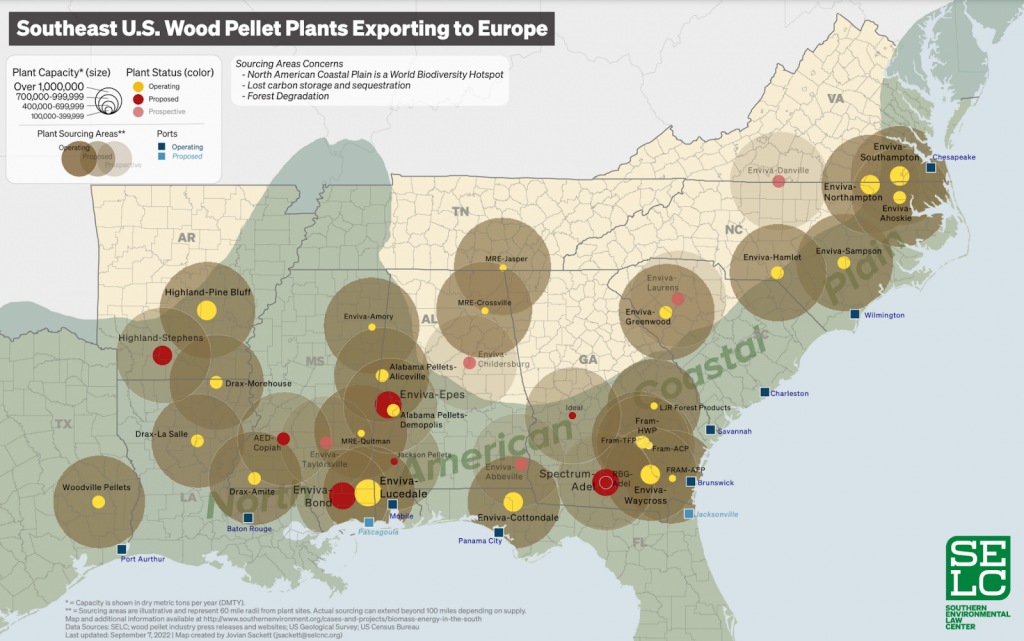

Currently 13 wood pellet processing plants are under consideration for construction across the Southeast and five plants are in the prospective phase of development in southern communities, according to the SELC.

Map of proposed and operating wood pellet sourcing areas, updated September 2022. Map produced by Southern Environmental Law Center.

“The wood pellet industry in general has really ran kind of this greenwashing campaign where they promote themselves as being clean and green, renewable energy, you know, even the name ‘biomass,’” says Emily Zucchino, director of community engagement at Dogwood Alliance, a nonprofit that works to protect southern forests. “I think that in the beginning, a lot of people were really kind of bought into this idea.”

Despite the wood pellet industry’s efforts to market this energy as clean, wood pellet companies still have “massive impacts on the region,” according to Zucchino.

“In North Carolina, [Enviva] destroys 164 acres a day. That’s massive, massive amount of forest land,” Zucchino says, adding that wood pellet companies “are logging and destroying forests” in almost every county east of Raleigh.

A Carbon-Intensive Fuel

Though wood pellets are classified as a renewable source of energy by the European Union, old forests hold a lot of carbon, and the trees planted by Enviva to replace them will not consume the level of carbon of the old trees for another 60 to 100 years, according to research from Chatham House, a policy institute.

This means that wood pellet biomass’ renewable potential does not fit within the Paris Climate Accords’ timeline to decarbonize energy grids by 2050.

After the trees are cut down, the processing, international shipping, and burning of the low energy dense biomass causes high rates of carbon emissions, according to a report from the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies.

Meeting global climate goals requires a move from coal and other fossil fuels, but woody biomass actually increase carbon emissions compared to other fuel sources in the short term, making effective emission reductions a hurdle, according to the National Resource Defense Council.

In 2021, Enviva, Equustock and other biomass-producing companies processed 14,634,100 Metric tons of wood pellets in the U.S., according to the trade publication Biomass Magazine.

The 13 plants proposed as of September 2021 would have produced approximately another 11,368,000 metric tons, according to the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“[Enviva] exports our forest overseas to Europe, but it is incredibly lucrative for them to come in, set up, destroy forests, pollute communities, and profit immensely off of it,” Zucchino says.

On November 17, Bell along with scientists, activists and residents told their concerns about Enviva to the North Carolina Environmental Justice and Equity Board, a board formed to advise the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s secretary on how to better serve vulnerable, at-risk and marginalized residents.

Bell says the meeting was exhilarating because she got to share her concerns. She remains optimistic that her activism will make changes and is motivated to keep moving forward with the challenges she and her community face.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment