Citizen Air Monitoring Network Grows Stronger in West Virginia’s ‘Chemical Valley’

Individual and organizational efforts are giving Appalachians more information about the air they breathe

By Joe Severino

Kathy Ferguson’s family had always attributed her grandfather’s health issues to air pollutants from the nearby rubber plant.

A longtime resident of Institute, West Virginia — a small, unincorporated town just west of Charleston on the Kanawha River — Daniel L. Ferguson suffered from cancer of the larynx later in his life. Kathy Ferguson remembers how when she was a child, her family members would discuss the mysterious black residue they would often find caked on their cars. She also remembers two environmental emergencies stemming from leaks at local factories.

The nearby Union Carbide plant, now owned by Dow Chemical, has long been a mainstay in Kanawha Valley, nicknamed “Chemical Valley” for the many petrochemical plants situated along the valley floor and Kanawha River.

For more than 75 years, it’s also been a major source of environmental hazards for local communities.

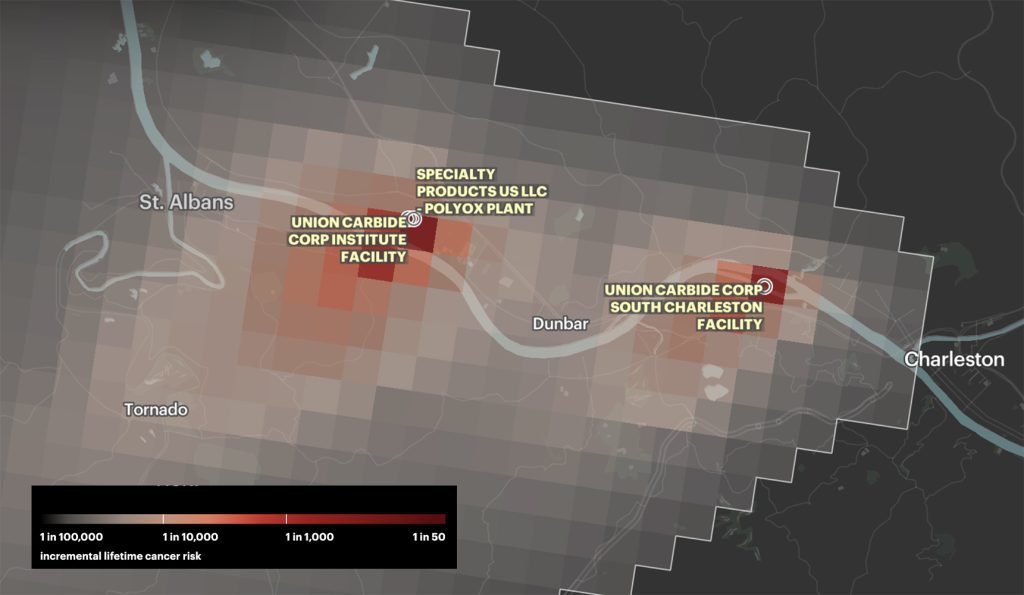

Residents of Institute, the only majority-Black census tract in all of West Virginia, have long been exposed to disproportionately high levels of air and water pollution. The risk of cancer near the Dow Chemical plant is 36 times higher than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s acceptable level, according to a ProPublica analysis. Other health issues are also prevalent in Institute — right next door to the plant.

In 1985, more than 100 residents near the then-Union Carbide plant were treated for eye, throat and lung irritation after a gas leak that garnered national attention. It came on the heels of a Union Carbide plant gas leak in Bhopal, India, just months before, which killed more than 2,000 people.

Pam Nixon, an Institute resident and former environmental advocate for the state Department of Environmental Protection, said her sickness resulting from the 1985 leak turned her into the activist she would become over the next 40 years.

“All I could think of was, [the death toll in Bhopal] was something that could have happened in Institute,” Nixon says.

Ethylene oxide, a cancer-causing chemical used by the Dow Chemical plant to make antifreeze, has been linked to increased risk of diseases like breast cancer, leukemia and lymphoma. Short-term exposure can lead to respiratory and skin irritation.

Kathy Ferguson, now a prominent community advocate one generation younger than Nixon, has picked up the torch and made environmental justice one of her top priorities.

“Our health outcomes are tied to the quality of our land, water, air,” she says.

Monitoring air quality

West Virginia Citizen Action Group, a civic engagement organization active since the 1970s, is one of a few community groups taking matters into their own hands. Through the strategic placement of PurpleAir monitors — devices that track and record levels of certain common airborne pollutants — the group is building a network of citizen air monitoring sites and volunteers throughout Kanawha County. PurpleAir monitors provide real-time data on a publicly available interactive map to track by-the-minute changes in air quality.

Morgan King, climate and energy program manager for WV Citizen Action Group, explains that her organization has helped place 41 air monitors around the state over the last couple of years. These monitors stretch from places like Lewisburg and Davis, where there is little nearby industry affecting typical air quality, to multiple neighborhoods throughout the Kanawha Valley.

According to King, they plan to place 30 more this summer. Four of the group’s PurpleAir monitors are in Institute. They have placed 15 total monitors throughout the Kanawha Valley.

Appalachian Voices, the regional nonprofit organization that publishes The Appalachian Voice, has also been collecting data with community partners from its own PurpleAir monitors since late 2023 as part of the Upper South and Appalachia Citizen Air Monitoring Project, or USACAMP. In West Virginia, those partners include Coal River Mountain Watch, a grassroots environmental organization in a community affected by coal mining, and the Institute Pinewood West Dunbar Sub Area Planning Committee, a community development organization focused on infrastructure and other community assets in Institute and surrounding communities.

More than 60 USACAMP monitors are currently installed at sites across Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. In the Mountain State, these monitors are dispersed throughout coal-mining areas in McDowell and Raleigh counties, with additional monitors in Beckley and Institute. Data from these monitors is being collected over a three-year period and analyzed against the federal standards for fine and coarse particulate matter, or PM2.5 and PM 10, respectively.

The goal of the project is to evaluate particulate matter levels in communities where the EPA is not actively collecting its own data.

Projects like the USACAMP and WV Citizen Action Group’s air monitoring network will give the public a better understanding of air pollutants in their neighborhoods in real time, according to King. A few years ago, many people in West Virginia could not find local information, as the state Department of Environmental Protection’s current ambient air quality monitoring network only covers portions of 12 of the state’s 55 counties. Though PurpleAir devices are less precise and reliable than the more expensive and complicated equipment used by regulators, West Virginians can now view the nonprofit organizations’ monitors publicly.

A vital step in growing WV Citizen Action Group’s air monitoring network will be storing this data and finding ways to use it effectively, King explains. Currently, they do not have enough data to track air quality trends over time. Once they acquire sufficient data, advocates will have a clearer picture of which neighborhoods and regions are most affected by air pollution.

King points to the success of citizen use of “methane sniffers,” which are small tools that the public is using to point inspectors in the right direction when looking for gas releases coming from unplugged wells. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection lists 16 oil and gas inspectors who are responsible for monitoring more than 100,000 wells.

Similarly, WV Citizen Action Group wants the community air monitoring network to help track air pollutants.

Facing headwinds

Community air monitoring has barriers in a place like West Virginia. PurpleAir sensors retail for nearly $300 and require a stable internet connection. In a rural state where average household incomes are some of the lowest in the nation, organizers said there are financial and logistical hurdles to expanding this program.

The West Virginia Manufacturers Association has also sought to thwart community air monitoring as these projects take form. Industry lobbyists have worked in the West Virginia statehouse in recent years to craft legislation barring any official use of this data, including as evidence in lawsuits and regulatory enforcement.

Mountain State Spotlight, an investigative news outlet in West Virginia, reported the Manufacturers Association worked with the Chemours Company to lobby for this legislation. Chemours operates a chemical plant in Belle, a small town about 20 miles upstream from Institute.

The bill failed to pass in 2024, with some lawmakers citing concerns that the attempt to bar courts from considering community air monitoring data violates the equal separation of powers amongst the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government. In 2025, proponents of the anti-community air monitoring bill agreed to drop the provision restricting courts, but the legislation failed to pass for the second year in a row.

Passing down knowledge

Back in Institute, Ferguson describes her efforts in recent years to inform the area’s newer residents of the risk of air pollutants. Over the past couple of decades, the town has lost much of the “old guard,” Ferguson says, and new families have moved in without knowing much about Institute’s history.

“Institute was a very homogeneous place,” she says. “It just wasn’t really that kind of community anymore.”

Ferguson explains that concerns about the environment can be tough to relay to working-class families who are trying to just put food on the table.

“I think there is a lot of resistance and a lack of capacity to really be interested in this issue beyond just knowing. Folks in West Virginia, across the board, irrespective of race, are dealing with bread and butter issues,” she says. “To have this other thing that you can’t see — it’s easy to sort of ignore it.”

People are generally appreciative of her advocacy, Ferguson adds. But the conversation usually ends there.

“It’s one of those things where unless something really happens, folks are okay to just know, and not do,” she says.

Ryan Kirkpatrick, 22, is one of the Generation Z environmental advocates working in West Virginia. A lifetime resident of nearby Charleston and current student at West Virginia State University, Kirkpatrick said he became aware of the issue of air pollutants in Institute at a young age. He went door-to-door in the community conducting surveys about health outcomes, and found that nearly every person either had cancer themselves, had a relative with cancer, or had a relative who had died in recent years of cancer.

“I related to them,” says Kirkpatrick, whose mother suffers from Crohn’s disease, which has been linked to chemical air pollutants.

Kirkpatrick said his mother attended an alumni event at West Virginia State University years ago to find a half-dozen classmates were also suffering from Crohn’s disease. WVSU, a historically Black university, is adjacent to the chemical plant.

He is also concerned about severe flooding worsened by a warming atmosphere. Kirkpatrick has volunteered with flood recovery efforts in the past, and comments that there is a “hopeless” feeling when helping children and families sort through the remains of their water-ravaged homes. But he thinks it’s important to keep doing the work necessary to fight climate change and air pollution that started generations ago.

Kathy Ferguson’s father, Warne Ferguson, and Mildred Holt were two community icons Pam Nixon named most essential to first bringing awareness to the environmental racism happening in Institute. Nixon thanked “the old guard” that came before her — principled advocates who championed their community throughout their lives, reminding naysayers that Institute was a thriving community and college town long before the Union Carbide plant moved in.

“The community and the school were there before the facilities moved there. That community has been around for 140-plus years,” Nixon says.

As for solutions, Ferguson supports legislation that would put a moratorium on new chemical or energy plants in Institute. She argues that addressing the air quality and negative health outcomes that have come from these plants is far more critical than any jobs a new facility would create.

Additionally, Kirkpatrick believes financial compensation should be directed toward Institute residents who have suffered from cancers and other diseases linked to increased air pollution.

Community air monitoring is one big step in the right direction toward keeping chemical companies honest with their neighbors next-door, according to Nixon.

“We still have to be vigilant in holding the companies accountable for what they’re doing when they’re working within our communities,” she says.

Citizen air monitoring in the Mountain State could be more important than ever, as West Virginia Gov. Patrick Morrisey has deemed data centers the critical centerpiece of his economic development agenda. These data centers, which are largely unregulated and require copious amounts of energy and fresh water, also release air pollutants into nearby neighborhoods.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment