The Significance of the Battle of Blair Mountain, 100 Years Later

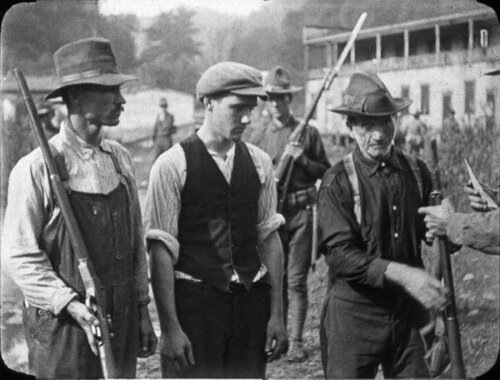

The National Guard confiscated these arms from pro-union miners during the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912. Photo courtesy of West Virginia & Regional History Center

Organizers of the centennial commemoration of the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain — a five-day clash between pro-union coal miners and anti-union forces that included state police, mine guards, Logan County Sheriff’s deputies and, eventually, U.S. troops — wanted to do more than mark an important historical anniversary.

“We wanted to bring together a whole bunch of partners across the state, region and even the country to put on some programming that will get people thinking, talking and wondering more about this era in history,” says Catherine Moore, president of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum Board of Directors.

Dozens of events across West Virginia will be happening in the weeks before and after Labor Day to commemorate the battle and its legacy. The current listing of events can be found at blair100.com/events.“I hope the events surrounding the centennial can bring the Battle of Blair Mountain back to the forefront,” says Brian Lacy, International District 17 vice president of the United Mine Workers of America. “That kind of history isn’t taught in schools. It’s kind of forgotten. I hope these events get people thinking about what the actual march was and the importance for the labor movement.”

The Battle of Blair Mountain followed years of tension, hostility and outbreaks of violence as the UMWA and its supporters worked to unionize the West Virginia coalfields in the face of fierce opposition from coal companies and the local politicians who were often deep in the coal companies’ pockets.

“The Battle of Blair Mountain was the culmination, the climatic event of the West Virginia Mine Wars,” says Chuck Keeney, a West Virginia historian whose great-grandfather Frank Keeney helped lead the fight on behalf of union miners. “At its core, the revolt was a challenge to the industrial power structure in the United States, with the miners trying to gain individual liberties denied under the mine guard system.”

Detectives from Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, a private security agency, were used by coal companies as muscle, enforcers and spies. They often helped evict striking miners from company housing — an act that in 1920 led to the Matewan massacre when Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield tried to intervene. The shootout resulted in the deaths of Matewan’s mayor, two miners and seven detectives.

The murder of Hatfield by a Baldwin-Felts detective on the steps of the McDowell County Courthouse in Welch is widely recognized as the spark that ignited the battle.

Ammunition shells from the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain are on display in Matewan, West Virginia, at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. Photograph by Roger May, Collection of the WV Mine Wars Museum.

The article continues, “As many as ten thousand of them tied red bandanas around their necks, took up arms, and began to march from Marmet, West Virginia, towards Mingo County, where they were intent on freeing their imprisoned union brothers and unionizing all the territory along the way. One observer estimated that about a quarter were African Americans, a quarter were immigrants and the rest were local whites.”

The army didn’t make it to Mingo County. At Blair Mountain, they were confronted by an anti-union army led by Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin — who was paid handsomely by the Logan Coal Association to keep the unions out of the county.

The ensuing battle raged for five days. It was the largest armed conflict on American soil since the Civil War. Chafin’s army had machine guns and biplanes that dropped tear gas and bombs on the miners. The fight didn’t end until U.S. Army soldiers arrived. Union miners — many of them veterans recently returned from World War I — were unwilling to fire on U.S. troops.

Many miners who took part in the battle were charged with treason and other crimes.

“The immediate consequences were that the treason trials bankrupted the UMWA in West Virginia and gave enormous momentum to the open shop movement,” says Keeney. “There were injunctions against the union in West Virginia mines. West Virginia went from 50,000 union miners down to less than 1,000 in less than five years.”

This still image from a 1921 Kinogram newsreel shows pro-union miners turning in their weapons. The footage was filmed after the Battle of Blair Mountain, and would have been shown to theater audiences across the United States. Collection of Kenneth King, West Virginia Mine Wars Museum

The union made a comeback under the New Deal during the 1930s when labor rights were strengthened, but there were long-lasting consequences in West Virginia.

“Coal got a stranglehold over the legal systems in the state,” Keeney says. “It sets the tone for the power structure that exists in the coalfields to this very day. Little county fiefdoms are essential to maintaining coal’s hold over this region. Local politicians profit greatly from the industry and jealously guard its interests.”

Christy Bailey, executive director of the National Coal Heritage Area & Coal Heritage Trail, a West Virginia-based unit of the National Parks Service, hopes one legacy of the commemoration will be a renewed interest by the people of the coalfields in working together.

“One of the things in our work is that we try to unite people in 13 counties and get them to see themselves as connected,” she says. “The commemoration has made people think about how solidarity improved the lives of miners, their families and communities. Reuniting the coalfields and maybe coming up with more large-scale common events or a common purpose — that would be a great long-term outcome to continue that connection across the coalfields.”

The centennial celebration, made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, has been in the works for years, according to West Virginia Mine Wars Museum Director Mackenzie New-Walker.

“We want to make sure Blair Mountain takes its rightful place in the state’s and nation’s memory,” she says. “It’s grown way beyond Mingo County. It’s incredible to see how many people and organizations have lined up in support — museums, unions, individuals, other organizations.”

The kick-off event is Friday, Sept. 3, at the Charleston Coliseum & Convention Center. Doors open at 4 p.m. There will be vendors and exhibits, as well as string bands, dance workshops, mine war reenactors, storytelling and historical interpretation. Admission is free. Due to the current rise in COVID-19 cases, masks and social distancing are required and the event will be at half capacity.

At 7 p.m., there will be a concert featuring Phil Wiggins and Gerry Milnes, who worked on the soundtrack for John Sayles’ 1987 film “Matewan,” and Heather Hannah, a songwriter who grew up in West Virginia’s coal-impacted region. In between musical acts, there will be presentations from folklorists and documentarians and a remote performance from poet Crystal Good. Tickets for the concert are $15.

On the same day, organizers are hosting events in Beckley, Madison and Morgantown, and UMWA members will begin a recreation of the miners’ 50-mile march from Marmet to Blair Mountain.

“Over the weekend, there will be events in Mingo, Boone, Logan, Kanawha, McDowell, Raleigh and Monongalia counties,” says New-Walker. “There is something for everyone.”

New-Walker encouraged those interested in attending events to keep an eye on the event calendar for updates.

“We are event planning in a very fluid time,” she says. “We have to be flexible in our plans because of Covid considerations. We are committed to keeping our volunteers and our visitors safe. We will keep the website up-to-date with any last-minute changes.”

On Sunday, there will be a walking tour of Matewan. UVA-Wise put together a lecture series and Marshall University will be hosting a a film festival about labor history and Blair Mountain.

“There’s a ton happening,” says New-Walker.

The UMWA annual Labor Day picnic and rally will cap off the weekend. UMWA President Cecil Roberts will speak, and there will be free food and activities for children.

Organizers hope the commemoration will serve to connect the events of Blair Mountain with the labor struggles of today.

“Obviously, we’re in different times than we were in the early 1920s,” says Lacy. “But we are still fighting some of the same struggles with workplace safety, shorter hours, fair pay, good benefits.”

Keeney agrees. “Many of the predicaments that we’re in right now from a labor-management standpoint — worker rights, private security companies, forced child labor — what we’re seeing is that these conditions are the result of a collective lack of remembrance of Blair Mountain,” he says. “I hope this commemoration is the beginning of a reevaluation of our region’s history, our relationship to coal, our local political structures and the need for reform at the local level — and also, of course, that these issues are relevant today at various places all around the world.”

Catherine Moore of the Mine Wars Museum is concerned about today’s labor environment. “Today in America in 2021, we’re seeing an erosion in workers’ rights that has been really troubling to me,” she says. “We had a golden moment in this country where unions had power and rights guaranteed to them. Those rights have been struck down across the country. In a lot of ways, under very different conditions, the Battle of Blair reminds us what the country looked like the last time unions didn’t have much rights or security.”

For Keeney, Blair also showed what happens when marginalized groups work together.

Emphasizing that he doesn’t want to romanticize or exaggerate it, Keeney states that it was remarkable for the time for immigrants, Black people and poor local White people to join together for a common cause.

“The Battle of Blair Mountain demonstrates a glimpse of what is possible when those groups unite,” says Keeney. “In our system and in the culture wars, those groups are often pitted against one another.”

New-Walker also hopes the centennial will result in changes at the location of the battle. “If you go to Blair Mountain today, if you blink, you’ll miss it,” she says. “I hope the 100th anniversary will serve as a springboard for future projects that will help us remember Blair Mountain.”

The Battle to Preserve Blair Mountain

In 2011, more than 1,000 advocates marched on Blair Mountain in an effort to save the historic site. Participants also called for an end to mountaintop removal, stronger labor rights and more sustainable jobs in the region. Photo by Appalachian Voices

The National Register of Historic Places listed the 1,600-acre Blair Mountain Battlefield in 2018 — for the second time.

The site was originally placed on the historic register in 2009, protecting the site from surface mining by the two coal companies that held permits for the area. But just months after Blair was first placed on the historic register, in December 2009 the National Park Service revoked the designation after a formal request from former West Virginia State Historic Preservation Officer Randall Reid-Smith.

A number of environmental and history groups became involved in legal proceedings to restore protections to the site. Supporters of the historic designation — including Appalachian Voices, which produces this publication — gathered in 2011 to recreate a portion of the storied march to Blair Mountain and raise awareness about the threat that mining posed to the site.

“Reaffirming the Blair Mountain Battlefield’s status on the National Register honors those brave West Virginia workers who fought for the right to organize for fair and safe working conditions,” said Cindy Rank, chair of West Virginia Highlands Conservancy Mining Committee, in a 2018 press release when the relisting decision was announced. “It also serves as an important reminder for all of us that the struggle is never easy.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “The Significance of the Battle of Blair Mountain, 100 Years Later”

-

Great article, thank you.

Leave a Comment