To Stop an American Extinction Crisis, the Southeast Must Pivot Away From Fossil Fuels

Guest column from Perrin de Jong, attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity

Few species better encapsulate the urgency of the extinction crisis in America’s Southeast — and the entrenched resistance to conservation efforts by industry and government political appointees — than the Guyandotte River and Big Sandy crayfishes.

Both species have been pushed to the brink of extinction by habitat loss caused primarily by mountaintop removal and other forms of coal mining. Yet despite these crayfishes winning federal protections under the Endangered Species Act in 2016, state officials have worked with federal appointees to ensure that mining can still take place in their habitat — which, for the Guyandotte River crayfish, now consists of only two streams in Wyoming County, West Virginia.

The dominance of fossil fuel companies across Appalachia has reached an inflection point. For the first time in American history, renewable energy is cheaper than coal. Yet despite the market pressures pushing fossil fuels into the realm of expensive obsolescence, many forces at all levels of government across Appalachia remain committed to extracting every last ounce of coal and fracked gas from the region, regardless of the consequences for human health and wildlife.

It doesn’t have to be this way for Appalachia, a region whose people have benefitted so little from the wealth that coal and gas companies have ripped out from under their feet. Nearly a quarter of Appalachia’s residents live in poverty, and unemployment rates here are consistently higher than the national average.

Further, a staggering number of species are staring down the barrel of extinction because of ongoing mining and fossil fuel development across Appalachia and the greater Southeast.

We have the tools to prevent this mass loss of life and the climate havoc it perpetuates, primarily through the use of the federal Endangered Species Act. What we lack is a government with the political will to follow the law, even when that means saying no to fossil fuels.

For many in the United States, the extinction crisis is an abstraction, an event happening in a poorly defined, faraway place — maybe around the melting polar icecaps or in the slash-and-burn destruction of the Amazon rainforest. Yet one of the worst chapters of this crisis is playing out here in America’s Southeast, a region that rivals the rainforests with its staggering array of aquatic biodiversity.

The Southeast contains more than two-thirds of North America’s species and subspecies of crayfishes and more amphibians and aquatic reptiles than any other region. Nearly all U.S. mussel species, 91%, are found here, as are 62% of the nation’s freshwater fish species.

While the warming of the Arctic and destruction of Amazonia have commanded headlines around the world, the ongoing destruction that the Southeast has endured at the hands of mining companies, frackers, factory farms, dams, logging and development captures only a tiny fraction of the attention.

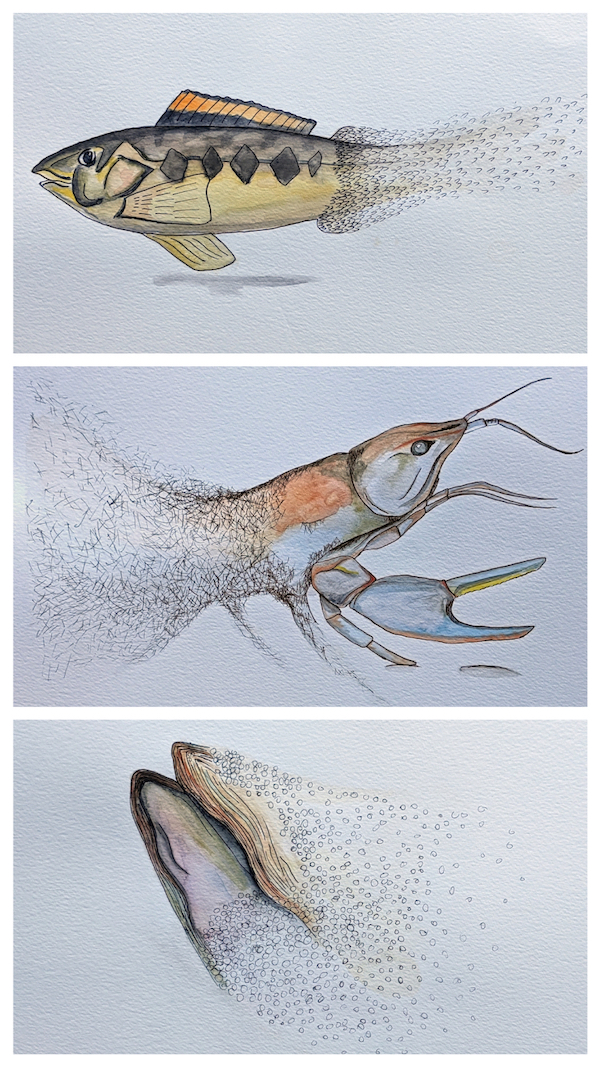

More than 1 million acres of hardwood forest and more than 2,000 miles of streams have already been wiped out by surface coal mining alone in Appalachia. Nearly a third of the region’s fishes, half of its crayfish, and more than 70% of its mussels face looming extinction.

Nearly a third of Appalachia’s fishes, half of its crayfish and more than 70% of its mussels face looming extinction. Art illustration by Courtney Alley

The Southeast can combat this extinction crisis, first, by tapping into the protections offered by the Endangered Species Act. Hundreds of imperiled plant and animal species, from the eastern black rail to the Atlantic pigtoe mussel, are locked in a bureaucratic limbo waiting for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to perform its legal duty to list them under the Act.

Protecting even a single species under the Act can make a difference, especially when critical habitat is designated. This requires a federal agency that’s funding or permitting any project to consult with the Service to make sure threatened or endangered species and their critical habitat would not be harmed before the project can be implemented.

Threatening the Southeast’s biodiversity is an entrenched, corrupt bureaucratic regime at the state and federal level that has long conspired to undermine the effectiveness of our environmental laws.

This resistance has been bolstered by new proposals by the Service to weaken the Endangered Species Act by changing the definition of “habitat,” severely limiting the government’s ability to protect habitat that imperiled animals and plants will need to survive and recover. Another proposal would give special weight to requests from industries like mining companies to reject habitat designations in areas eyed for development. We can’t allow these changes to be made.

At a time when everything seems to be heading in the wrong direction, we need to recognize our power to bring about a future worth living for. Conservationists and academics can pool money, staff and expertise with state and federal agencies to not only protect our imperiled aquatic species, but restore their habitat and expand their range.

Related: Get to Know Appalachia’s Vulnerable Species

That’s exactly what the Center for Biological Diversity has done in a recent initiative that provides over $45 million in state money to protect and restore habitat while funding captive propagation for eastern North Carolina’s dwindling aquatic species. The fund also provides for extensive water-quality testing so that newly bred individuals are reintroduced into clean, new habitat where they can thrive.

This initiative will promote the protection, expansion and recovery of imperiled aquatic North Carolina species like the dwarf wedgemussel, yellow lance, Atlantic pigtoe, Carolina madtom, Neuse River waterdog and magnificent ramshorn for years to come.

Conditions are dire, and civil society must respond with vigilant and defensive measures while advancing forward-thinking, proactive initiatives that give us all reason to hope for a livable future. But first, residents of Appalachia and the greater Southeast who care about the future of our region must stand in the breach and ensure that the proposed rollbacks to the Endangered Species Act never see the light of day. Protecting the wild plants and animals that make our region unique also helps ensure the long-term wellbeing of the people who call it home.

Perrin de Jong is a Center of Biological Diversity attorney based in Asheville, North Carolina.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment