The Impacts of Coal Bankruptcies

A valley fill near the Rush Creek coal mine in Kanawha County, W.Va. This is one of 60 mines that bankrupt Revelation Energy and its affiliate Blackjewel had not sold as of Feb. 5. Unfinished reclamation at the mine has led to extensive water pollution in nearby waterways. Photo courtesy of Kanawha Forest Coalition

The year had scarcely begun when Eastern Kentucky coal miners once again stood in the way of a train full of coal to demand pay for weeks of work. About a dozen current and former American Resources miners took to the tracks on Jan. 13 in Pike County, Ky., and stated that they had not been paid since Dec. 27, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader.

This came not even six months after a worker-led protest in Harlan County, Ky., against Revelation Energy and its affiliate Blackjewel, LLC, for unpaid wages in 2019. The companies clawed back paychecks after declaring bankruptcy in early July, leaving many of their roughly 1,700 employees with overdrawn bank accounts.

In October, Blackjewel agreed to pay the miners the $5.1 million they were owed after months of squabbling in bankruptcy court. In American Resources’ case, the company paid all wages owed after two days and the state closed four of the company’s mines in late January for failing to have workers’ compensation coverage and not paying all employees.

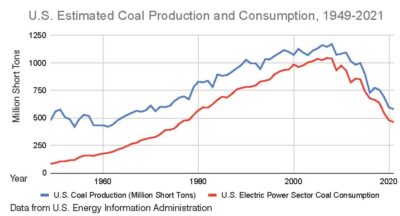

This turmoil is yet another sign of the industry’s struggles. Eight coal companies declared bankruptcy in 2019, including Murray Energy, the nation’s largest privately held coal company at the time of its bankruptcy. This marks 11 coal bankruptcies since President Donald Trump took office in 2017 with the promise of reinvigorating the declining industry — and 2020 looks worse for coal companies, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

When Congress passed surface mining regulations in 1977, federal and state rules included bonding requirements to ensure that mines would no longer be abandoned without sufficient cleanup funds. Ever since, mine operators have been required to post bond money upon opening a new mine to ensure that regulatory authorities can reclaim the land if the operator is unable to, typically due to bankruptcy. The 1977 law requires companies to reclaim the land in order to get their bonds back, which happens in phases as reclamation proceeds and inspectors sign off on the results.

Now that the coal industry is in its twilight years, a few companies have been unable to fulfill their reclamation obligations. If this continues, Kentucky and Virginia are among those that could face massive cleanup costs that outweigh the millions of dollars set aside for reclamation.

Blackjewel Debacle

Revelation Energy and Blackjewel hold $164 million in reclamation bonds in Kentucky. This is according to a Jan. 13 letter from the state Energy and Environment Cabinet to the federal court sorting out the companies’ 2019 bankruptcies. But Kentucky’s bond amounts are not always high enough to cover the real cost of repairing damage to land and water. When the state agency analyzed the cleanup costs for only 20 percent of Blackjewel’s mines in Kentucky, it found that reclamation would cost at least $202 million — a $38 million shortfall that does not include the majority of the company’s mines.

A contour cut at Revelation Energy’s Rush Creek coal mine in Kanawha County, W.Va. Photo courtesy of Kanawha Forest Coalition

While 161 other Blackjewel permits in Kentucky have buyers as of Feb. 5, state regulators told the court in a letter that they had only received six permit transfer applications. Additionally, the Energy and Environment Cabinet stated in its letter that Blackjewel had failed to pay any fees into Kentucky’s bond pool for any of its permits, and that those fees must be paid in full before any permits can be transferred.

Blackjewel stated in a December letter to the court that the reclamation costs of any unsold permits would be left to the third-party surety companies that insured them. In practice, this means that the surety companies will determine whether it is more cost-effective to hire out the reclamation work themselves with the bond funds or release the bonds to the state.

The bankrupt company’s environmental problems continue. When Blackjewel declared bankruptcy in July, it already had 121 environmental violations in Kentucky alone. While it had resolved 12 of those by mid-January, Kentucky regulators stated that Blackjewel had racked up 280 new violations in the state since declaring bankruptcy, according to a Jan. 13 letter from the Kentucky agency to the court.

The company’s attorneys have claimed that Blackjewel does not have the financial resources to address these violations. But the state found that the company has approximately $19.9 million in liquid assets and stated that those funds should go toward environmental cleanup.

At a Jan. 15 bankruptcy hearing, Mary Cromer with the nonprofit Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center spoke on behalf of several community groups including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper.

“As these mine sites are sitting, their conditions are degrading, the failure to maintain them is ultimately increasing the cost of reclamation. And that increased cost of reclamation, for the mines that are going to be abandoned, is going to fall on the citizens that we represent,” said Cromer.

Complicating the case, former Blackjewel CEO Jeff Hoops claims that the company owes him nearly $30 million — but Blackjewel attorneys asserted that Hoops fraudulently transferred tens of millions of dollars to his personal accounts prior to the bankruptcy. In 2019 alone, Hoops and one of his other companies allegedly took more than $41 million, according to Blackjewel attorneys.

Former employees are still dealing with the fallout of Blackjewel’s mismanagement. The company and its affiliates stopped making timely payments toward their employee health insurance plan after declaring bankruptcy. This means that health care providers are seeking payment for healthcare costs that employees incurred between early July and the plan’s cancellation on Aug. 31.

As of Dec. 11, there were more than $9.5 million in unpaid claims filed by medical providers of the former employees. As a result, the miners could be on the hook for thousands of dollars in medical bills.

On Jan. 21, Blackjewel lawyers asked the court to stop individual healthcare providers from taking debt collection measures for four months. The dispute between Blackjewel and UnitedHealthcare remained unresolved as of press time in mid-February.

The mess left behind after a coal company declares bankruptcy is far-reaching in terms of both the effects on the land and on the people. While these situations can vary, they are unfortunately becoming more common.

“More companies are going to go bankrupt, and more permits will get forfeited,” says Appalachian Voices’ Central Appalachian Senior Program Manager Erin Savage. “In the past, most bankruptcies have been reorganizations, where companies sold off permits to other companies. Since coal is dropping even more in 2020, reorganizing and selling failing mine permits to other companies is not a viable strategy anymore.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment