A Quest to Protect At-Risk Bats

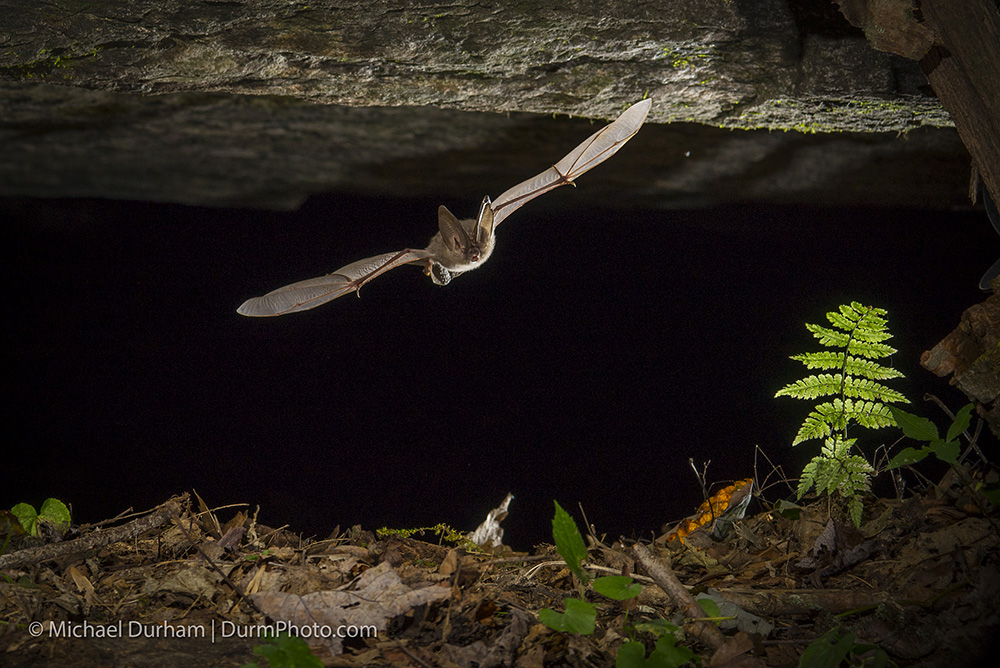

A Virginia big-eared bat swoops out of a cave in North Carolina. Researchers estimate that there are only 19,000 of this endangered species left in the wild. Photo by Michael Durham | DurmPhoto.com

“When I got in there, there were probably 150 bats on the ceiling, and at that point I basically knew that that was the spot,” says Weber.

The project began when the state proposed widening part of state Highway 105 in northwestern North Carolina in 2010, which triggered a study on how endangered species might be affected.

“We knew the [bats’] hibernation site was near there, but we didn’t know where the maternity site was, and we had concerns about that,” says U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife Biologist Sue Cameron. The bats use different caves for hibernating in the winter and for birthing and raising pups in the summer.

“We had concerns about whether the widening project could act as a barrier to the bats or impact their foraging habitat at all,” she says.

Finding the Roost

Joey Weber listens for signals from the radio tags he and other researchers attached to 19 Virginia big-eared bats in 2013. Photo courtesy of Indiana State University

“It sends out a pulse every couple of seconds, and with that you can listen for a louder signal,” says Joey Weber. “Whichever way your louder signal is coming from is the direction of the bat.”

The researchers knew that the bats hibernate in a cave on Grandfather Mountain. So in late March and early April 2013, they went in with special gear and plucked several bats off the ceiling. If the bat looked to be a healthy adult, researchers would trim the fur on its back and use surgical glue to attach a tiny radio tag about the size of a fingernail, with an antenna sticking out several inches.

“It doesn’t seem to impair their flight, as far as we can tell,” says Joy O’Keefe, lead researcher of the project and director of Indiana State University’s Center for Bat Research, Outreach, and Conservation.

Researches in protective gear attached radio tags to 19 Virginia big-eared bats. Photo courtesy of Indiana State University

To prevent bites, O’Keefe’s technicians wear leather batting gloves — more commonly used to handle bats on baseball fields — which allow more dexterity than work gloves. These are also boiled between visits and are worn under latex gloves that are discarded between bats.

Many individuals in this population of Virginia big-eared bats already carry white-nose syndrome. But strangely, O’Keefe states, no related fatalities have been recorded.

“We’re not really sure, this is just speculation on my part, but possibly the fact that they live in caves all the time has helped them to ward off the disease whereas other bats that move out of caves in the summer are less resistant,” says O’Keefe.

Researchers are careful when handling bats, as they are surprisingly delicate — O’Keefe notes that Virginia big-eared bats weigh about the same as 10 paper clips. When picking up a bat, she states that they can often be “pretty squirmy,” but that this species is typically more docile.

“It seems like each bat has their own personality,” says Joey Weber. “Some of them don’t react much at all, they just kind of sit still and let you do your thing until you let go, but then some of them will try to bite you and get offended by you handling them.”

“Some of them try to look mean, but it’s really hard for them to be mean when they’re so small,” he adds.

A cluster of hibernating Virginia big-eared bats in Pendleton County, W.Va. Photo by Craig Stihler/WVDNR

Once the bats were tagged, finding the maternity roost was no easy task — according to Sue Cameron with the Fish and Wildlife Service, researchers had been searching for more than 30 years.

“The rocks in that area can really throw you off,” says O’Keefe. “You could be standing at the side of the road pointing your antenna at the mountain and it might sound like the bat is there, but it’s actually completely 180 degrees behind you and it’s just the signal bouncing off the mountain.”

But Joey Weber was able to track the bats to an area near North Carolina’s Beech Mountain roughly eight miles from Grandfather Mountain as the bat flies. Weber credits much of the success to the multiple radio receiver towers the team erected around the area to record the bat signals.

“That was pretty new and different than most other bat studies,” he says.

Protecting the Land

The maternity roost and the surrounding 174 acres of land became a North Carolina state natural area in 2017. Had the roost not been found in 2013, however, this story could have a very different ending — the land was slated to become a housing development.

“The Virginia big-eared bat is known to be highly sensitive to disturbance,” says O’Keefe. Housing development around the cave could severely affect the bats’ foraging territory, and the bright lights could make the bats more susceptible to predation. The bats might even abandon their pups.

“Sometimes people go and close off holes in the ground like that, which would be really devastating for the bats,” says O’Keefe.

Once researchers discovered that the area might be developed, they reached out to the Blue Ridge Conservancy, a nonprofit land trust dedicated to protecting natural spaces in North Carolina’s High Country. The conservancy and multiple state and federal agencies collaborated to purchase the 174 acres from eight separate landowners and transfer it to the state park service. In a rare turn of events, all eight landowners agreed to sell their property to the state for conservation purposes.

Four Incredible Facts About Bats

- Bats are the only major predators of night-flying insects. A summer colony of 1,000 bats can consume 22 pounds of insects each night, or as many as 4.5 million insects.

- The heart rate of a hibernating bat slows to only one beat every four or five seconds, while the heart rate of a bat in flight is over 1,000 beats per minute.

- Because their bodies are so well-adapted to hibernation, a bat can survive on only a few grams of stored fat for a five-month winter.

- Most bats breed in autumn but females will store the sperm until fertilization takes place in the spring.

— Amy Renfranz, Grandfather Mountain

“It was very pleasantly surprising,” says Eric Hiegl, the conservancy’s director of land protection and stewardship.

While the groups raised enough funds, a private philanthropist purchased and held the land to ensure no development took place.

“It’s really an awesome example of partnership with all the organizations,” says Nikki Robinson, communications and outreach associate for the conservancy. “They each had something really important to bring to the table.”

Since the Virginia big-eared bat is sensitive to disturbance, the conservancy is not disclosing the cave’s location.

“This isn’t going to be a campground or hiking trails, that kind of place,” says Hiegl. “Resource protection is the number-one reason for this.”

O’Keefe states that it’s important to preserve the maternity roost because this endangered species is native to North Carolina’s High Country.

“There’s no other places in North Carolina where you can find that species, so it’s a really unique and iconic species for the region,” says O’Keefe. “I think that’s important, the character or flavor of that area that is found nowhere else.”

Blue Ridge Conservancy and Appalachian State University Documentary Film Services produced a short film about this project. View it online at tinyurl.com/brc-bats-video.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment