Following Cherokee Footpaths

A quest to document and preserve Southern Appalachia’s indigenous trails

By Kevin Ridder

“This trail system is the circuitry and the main arteries of all the main transportation systems today, especially the older transportation systems,” Lamar Marshall says, standing in an ancient Cherokee footpath later used as a U.S. Army wagon road and a Trail of Tears corridor. Photo by Kevin Ridder

Hundreds of years ago, before interstate highways drove through the mountains, a network of trails winding around the Southern Appalachians served as the arteries of the sovereign Cherokee nation. Carved by man and beast alike, the trails evolved following the curves and contours of the land.

Lamar Marshall, cultural heritage director of Wild South, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting the South’s wild places, has spent the last eight years pairing historical maps, surveys, journals and oral histories with geospatial mapping technology to bring this vast interconnected web to life. A background in engineering and land surveying provides him with an expertise in map reconstruction — a lifetime as an outdoorsman gives him everything else.

“What really got me was reading about Native Americans and how free they were,” Marshall says. “They lived off the land, they were totally independent and self-sufficient before the Anglos came in. I just admired the way they could live in the outdoors.”

Winding around the Appalachians with very little help from my GPS to Marshall’s homestead in Cowee, N.C., I soon found that his admiration extends far beyond that of a casual scholar; Lamar and his wife Kathleen live almost completely off the land.

Luckily, Marshall sensed my status as a city-dweller and had sent me in-depth instructions to his little house on the mountainside. After only three wrong turns and one stop for directions, I was pulling up their driveway with a trio of baying hounds close behind.

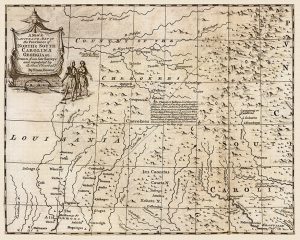

A 1747 canvas map of the Provinces of North and South Carolina drawn by Englishman Emanuel Bowen. It shows several historic Cherokee towns and settlements. Scan courtesy of Lamar Marshall

“Most of the food we eat is either hunted or grown out back in our organic garden,” Marshall says as we walk into his house. “Deer season starts up soon so we’ll have to make some space in our freezers. Remind me to give you a few bags of veggies.”

Walking upstairs to his office, Marshall pushes aside a heavy blanket that he says prevents their small but powerful wood stove from overheating the bedroom.

Countless papers and artifacts are stacked around his office, with just enough room for two people to sit in front of the four monitors lining the desk. Near the window hang several name badges from conferences where Marshall has presented his life’s work.

Various scans of 18th-century era maps and journals pop up on the monitors as the computer starts up. Marshall double checks the Wi-Fi hotspot on his phone; the fact that the internet company has yet to extend their service this far up the road hardly slows him down.

“In 1991, I moved into the Bankhead National Forest in Alabama, and the [U.S. Forest Service] was mowing it down,” Marshall says. “They were cutting down 200-year-old hardwood ridges, replacing them with monocultures of loblolly pine. Converted 90,000 acres into these plantations.”

Except it wasn’t just trees they were cutting down, Marshall explains. One of those clearcuts exposed Indian Tomb Hollow, an archaeological site in the heart of Bankhead National Forest sacred to regional Native Americans. Looters soon invaded the area and dug up several of the graves.

Outraged, the Blue Clan of the Echota Cherokee teamed up with Marshall and other locals to form the publication Bankhead Monitor and the nonprofit group Wild Alabama, with the goal of preventing future clearcutting of sensitive areas. Their efforts led to the protection of roughly 180,000 acres in the Bankhead National Forest.

In 2007, Wild Alabama became Wild South, an Asheville-based nonprofit that currently has more than 15,000 members dedicated to preserving the South’s environmental and cultural landscape. Since its inception, Wild South has helped protect half a million acres of land and numerous species of wildlife in North Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee and beyond.

Delving into the Archives

With grants and a seal of approval from the Cherokee Preservation Foundation, a nonprofit group funded by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Marshall and his team from Wild South have used archival records to map well over 1,000 miles of Cherokee foot trails and around 60 historic Cherokee towns and settlements in the last eight years.

“I not only map the trails and towns, but we also go to archives all over the East, including the National Archives in D.C., photographing old records to the extent that I have over 100,000 images,” Marshall says. “Instead of trying to pick and choose records, we go box to box and photograph them all for study when we get back. We’d never have time to go through them all when you’re at the archive.”

“By reading these old documents, letters and affidavits, you glean out these tidbits of geography and ecology,” he continues. “You begin to put together the big picture: that the trail system is continental wide.”

These files don’t just gather dust on Marshall’s hard drive, either. Every archival document he photographs is gifted to the Qualla Boundary Public Library in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians for genealogical research.

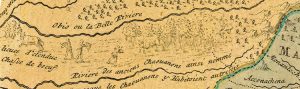

Lamar Marshall compares archival materials like this 1759 hand-drawn map to archival journals and land surveys to help find the location of old Cherokee trails and towns. Scan courtesy of Lamar Marshall

Russell Townsend, tribal historic preservation officer with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, says his work has benefitted greatly from having access to these files.

“We use those archive materials daily to research Cherokee history and culture,” Townsend says. “They run the gamut from some of the earliest English activity in the area in the late 1600s up to [Bureau of Indian Affairs] activities in the 20th century.”

“The knowledge gained from them is really important because it shows [the Cherokee foot trails] connected these communities in ways that the automobile roads don’t,” Townsend continues. “You realize that some places divided today by a 15 or 20 mile drive around a long ridge was really just four or five miles of a hard walk. Back in the 20th century and before, that kind of hike was nothing. So really a lot of communities are more connected historically than we thought, and that affects linguistic patterns, cultural patterns, material patterns — everything.”

Stepping Through Time

After exploring the history behind the trails, Marshall and I drive to the Needmore State Lands to hike a section of an ancient Cherokee foot path that eventually became part of the Trail of Tears.

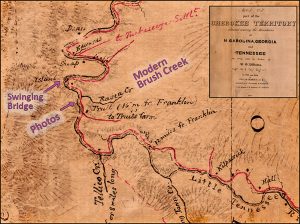

Coming to a stop by a swinging foot bridge, we cross the Little Tennessee River and begin our trek through the trees. Marshall deftly outpaces me as I attempt to fend off the thorny underbrush. Reaching the edge of the trail, I stop next to Marshall as a feeling of reverence settles over me.

“What you’re seeing right here are the exact mountains, the exact views that the Cherokee thousands of years ago saw,” Marshall says, looking off into the distance. “This is the vantage point where they were when they moved through the woods. To me, this isn’t just something that connects you to the past — it’s a portal to it.”

The path is clearly defined, with banks up to four feet high carved by a millennia of hooves and silent footfalls. A resounding crunch amplifies each step I take through the autumn river of leaves.

Lamar Marshall stands near the mouth of Brush Creek as he looks out over the Little Tennessee River. Photo by Kevin Ridder.

Once a Cherokee foot trail has been mapped and turned over to the U.S. Forest Service, Marshall tells me, it is automatically protected under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 until it has been studied for its significance. Afterwards it can be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. All of these trails are open to the public, save for the sections that run through private land. Many continue to be in use today as roads and hiking paths.

Due to its status as a Trail of Tears corridor, Marshall informs me, the trail we are walking on will almost certainly be nominated.

“There’s no way to tell how old these trails are,” he says. “They say Paleo-Indians got here 13,000 years ago. Now I don’t know if they’re that old, but it dates at the very least back to the Mississippian culture [between 800 CE and 1600 CE].”

“This is a natural walkway, too,” Marshall continues. “The buffalo could’ve even tunneled it. This right here is a jewel, it’s priceless. Not only to the Cherokees, but to everybody. And it could’ve easily gotten bulldozed away if we hadn’t identified it, mapped it and turned it into the state.”

To date, Marshall has mapped over 1,000 miles of trail with GIS and topographic maps and field-mapped over 200 miles by foot. He inputs each trail’s GIS data into a yet unfinished ArcGIS Story Map with the hope that it can eventually be used as an educational tool. Its completed form will have narrative, text, images and multimedia content layered over the trail network to provide a glimpse into our region’s past. Samples of the maps Marshall has created are available on the Wild South website. Out of respect for the Cherokee people, no sensitive, sacred or archaeological sites are shared with the public.

As this 1837 U.S. Army map to the left shows, Brush Creek was once known as Raven Creek. This map was used by Marshall to help put together the storied history behind the trail section we hiked. Scan courtesy of Lamar Marshall.

To thank him for his contributions to Cherokee cultural preservation, members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians gave him a name: Usdi-nvno Awatisgi, or “Trail Finder.”

“It’s really cool when you look at a map and see how interconnected things really were,” Russell Townsend of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians says. “There are stories about people who traveled on them regularly, various incidents that happened on them that are prominent to our history and culture. I think our elders are very pleased that the knowledge of these old foot trails is not going to be lost.”

To view some of the maps Lamar Marshall has created and find out more about the Cherokee journey, visit cherokee.wildsouth.org.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

4 responses to “Following Cherokee Footpaths”

-

Really enjoyed reading about Cherokee my very favorite place

-

How important for us to know…..

-

This is nice. I’d liked them to mention the British named the local Indians, Cherokee in 1693. I’d like to know the names of the people before given the name Cherokee.

-

This is a wonderfully written article. I enjoyed reading it and very thankful for Mr. Marshall’s efforts in helping preserve these trails and history.

Leave a Comment