Full Disclosure?

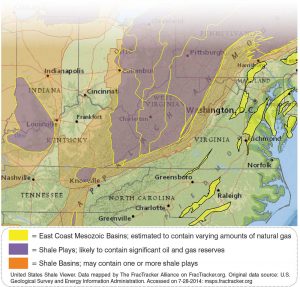

As North Carolina considers its first natural gas drilling rules, a survey of the region shows how states are — and aren’t — regulating fracking

By Molly Moore

When Denise der Garabedian heard that fracking could come to the area near her home in the Smoky Mountains of Cherokee County, N.C., she began researching the controversial method of gas drilling and talking to neighbors who had seen the effects of the fracking boom in other states. The more she learned, the more determined she became to speak out against the practice.

Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, involves drilling a well into shale rock formations and injecting a mixture of water, sand and chemicals at high pressure to fracture the rock, prop open the fissures, and then withdraw the natural gas and less than half of the fracking fluids. The rest of the fracking brine remains underground, where some scientists are concerned that it could migrate into groundwater.

The relative abundance of natural gas has made it a cheap source of power. But as shale gas production has skyrocketed — from 169,026 million cubic feet in 2007 to 902,405 in 2012 — concerns about water contamination have grown.

In January, an Associated Press investigation of water contamination in Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Texas found that some states have confirmed a connection between oil and gas drilling and well-water contamination.

Independent research points to similar conclusions. “A range of studies from across the United States present strong evidence that groundwater contamination occurs and is more likely to occur close to drilling sites,” states a compendium of research on fracking’s environmental and public health effects assembled by the Concerned Health Professionals of New York in July. Last year, a Duke University study in northeastern Pennsylvania found that higher levels of methane in wells near gas drilling sites were linked to shale gas extraction.

Proponents of fracking point to alternate studies — such as one conducted by the drilling company Cabot Oil and Gas — that they say disprove the conclusions drawn from other scientific research.

Still, there is no overarching scientific statement on how frequently fracking affects drinking water supplies or how those chemicals impact public health. In 2010, Congress ordered the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to conduct a comprehensive study on how fracking affects groundwater, but the release date for that study was pushed back from 2014 to 2016.

While they wait for answers, Appalachian states are moving ahead with fracking, their paths determined by a mix of geological happenstance, political will and citizen pressure. State-level decisions are even more important given a lack of federal oversight — fracking is exempt from federal laws that typically protect water, air and public health, such as the Clean Water, Clean Air, and Safe Drinking Water Acts. The industry is even exempt from Department of Transportation rules that set safety standards for the number of hours truck drivers can work. When states begin fracking, they venture into the Wild West of regulation.

Entering the Fracking Frontier

In 2012, the North Carolina legislature overturned the state’s fracking moratorium and created the Mining and Energy Commission to draft the state’s first natural gas drilling rules. Now, as the legislature accelerates the rulemaking process, the commission is at the center of a statewide debate.

“When the MEC formed and set out on this path they said they were going to make the strongest and most restrictive rules in the nation and since then everything they’ve done has been a step back from that,” says Mary MacLean Asbill, a North Carolina attorney with the nonprofit Southern Environmental Law Center.

The MEC proposals, released in July, would prohibit gas companies from injecting fracking waste underground, but would allow open waste pits. In fact, Asbill says, the draft rules don’t adequately address many areas of concern, including air emissions, liability for spills and baseline water quality testing to determine whether any water pollution problems are pre-existing.

The fracking industry’s exemption from the Clean Water Act also means that companies are not federally required to disclose the chemicals used in the fracking process. Instead, states have discretion to set chemical disclosure standards. North Carolina’s MEC proposals provide some safeguards on this front, but in June the state legislature passed a law making it a misdemeanor for anyone to reveal fracking chemical trade secrets, including doctors who would be granted access to the information in case of emergency.

In August and September, the commission is planning to hold public hearings to solicit input on the draft rules. Three hearings are scheduled in the Piedmont, and, after pressure from western North Carolina residents, the commission agreed to hold a fourth in the mountain town of Cullowhee.

Attention is centered on the natural gas potential of the Deep River and Dan River basins, where test drilling could begin this fall, but the state environmental agency also plans to test for indications of gas in seven western counties.

In the meantime, a recently formed grassroots organization called Coalition Against Fracking in Western North Carolina is organizing town hall meetings and urging local governments to take a stand against the practice. In July, several local governments stated their opposition to fracking, beginning with the Swain County Commission and the town of Webster in Jackson County. The North Carolina law passed in June invalidates local ordinances regarding fracking, but in other parts of the country such ordinances are gaining ground. New York’s top state court recently ruled that towns could use zoning laws to ban fracking near their borders.

As citizens in the western counties of North Carolina prepare for the public comment hearing in September, Denise der Garabedian will keep encouraging her neighbors to pay attention during the rulemaking process and beyond. “I know I can’t save the world, but I might be able to save my backyard and my neighbors’ maybe,” she says.

Science of Setbacks

Along with New York and Pennsylvania, West Virginia has been at the epicenter of fracking in the Eastern United States for a half-dozen years. The Associated Press reported that from 2009 to 2013, the state received roughly 122 complaints that drilling contaminated water wells and found that “in four cases the evidence was strong enough that the driller agreed to take corrective action.”

To address the boom, West Virginia passed a new set of rules in 2011 that environmental and property-rights groups criticized as being too weak; the West Virginia Citizens Action Group called them a “Christmas gift to drillers.”

Among their concerns, critics said that the buffer zones — designed to protect residents and water supplies from air and water pollution — were insufficient. In a 2013 study, Dr. Michael McCawley, a chairman at West Virginia University’s School of Public Health, found contaminants such as the carcinogen benzene in the air at seven drilling sites. Based on his research, he advised the DEP to stop relying on the boundary zones and instead conduct direct air quality monitoring near the sites.

His study was undertaken because of the 2011 law which required the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection to research several aspects of the oil and gas industry, including air pollution, and then use the results to implement additional rules if necessary. After reviewing McCawley’s findings, however, the DEP reported to the legislature that no rule changes were needed. McCawley then took his concerns directly to state legislators in the fall of 2013, where he says he received an encouraging response. He is continuing to pitch the idea to decision-makers in West Virginia and neighboring states.

Wastewater Worries

Although Kentucky and West Virginia share a long border of similarly rolling mountain ridges, their geology is distinct enough that the Bluegrass State hosts far fewer hydraulic fracturing wells. But that may be changing. Recently, successful tests in the state’s northeastern corner have led to more fracking in the area, and applications to drill are increasing.

Tim Joice, water policy director at the nonprofit Kentucky Waterways Alliance, notes that the state’s oil and gas drilling regulations are decades old and do not consider how modern processes could allow gas or fracking fluids to migrate into aquifers or wells.

Essentially, the existing regulations were written to address nitrogen-foam fracturing, not hydraulic fracturing. In much of the state, hydraulic fracturing doesn’t work very well because the high clay content in some of the state’s shale formations absorbs water. So, beginning in 1978, eastern Kentucky drillers began to combine nitrogen and comparatively small amounts of water — roughly 120,000 gallons — with other chemicals and sand to create a briny foam that is then injected underground at high pressure.

Nitrogen-foam wells have the advantage of using less water and producing less chemical-laden brine for disposal. Yet whether a well is fracked with nitrogen foam or hydraulic fracturing fluid, the resulting toxic waste needs to go somewhere. Often, it’s injected back underground in designated wastewater wells, but companies have also dumped the waste into streams and gullies near drilling sites.

When Kentucky Waterways Alliance requested information about complaints of improper disposal of fracking brine from the state, the Kentucky Division of Water responded with a spreadsheet of 360 incidents between January 2012 and May 2014, six of which have resulted in formal violations.

The 200,000-Gallon Question

In Tennessee, the greatest problem with regulations is simple — the rules don’t apply to most drilling operations in the state. Fracking rules the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation passed in 2012 only apply to wells that use more than 200,000 gallons of water. The relatively sparse fracking happening in Tennessee uses the nitrogen process, which uses far less water than the limit, so most operations are exempt from the rules.

“It’s a partial regulatory scheme but they don’t apply it most of the time, so what we’re left with is virtually nothing,” says Anne Davis, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center who had recommended stronger regulations. “If you frack with nitrogen you’re not doing more than 200,000 gallons.”

Operations that use more than 200,000 gallons must issue public notice of new fracking operations, test nearby water wells and provide monitoring reports. Fracking operations using less water still need to file a permit stating their intention to frack, but no public notice is required and the permits are not available online. Once drilling is complete, operators are obliged to disclose the chemicals they use, but this requirement only applies to those chemicals that aren’t classified as trade secrets.

Reviewing Regulation

In Virginia, as part of an ongoing review of fracking, a state regulatory advisory committee recently agreed to recommend that the Virginia Gas and Oil Board change state regulations to require full public disclosure of all ingredients in fracking fluids. In their ongoing meetings, the committee also discussed whether baseline groundwater sampling should be required before the agency can authorize drilling and fracking.

As the rules review continues, several natural gas proposals are keeping the issue in the spotlight. Oil and gas companies are interested in fracking the Taylorsville Basin in eastern Virginia, and one Texas company has already leased 84,000 acres. In the George Washington National Forest, which overlies part of the Marcellus Shale formation, the U.S. Forest Service is considering whether to limit hydraulic fracturing in the area.

New pipelines to carry natural gas from the Marcellus Shale through Virginia have also generated controversy. Routes for the three pipeline proposals aren’t final, but some nearby communities are already organizing to express concerns about oil and gas leaks. And Dominion Resources’ proposed 450-mile project would transport natural gas through the George Washington National Forest, which environmental organizations such as Wild Virginia say endangers natural areas and drinking water supplies.

Efforts to expand fracking and natural gas infrastructure in Appalachia are forcing residents and decision-makers to confront basic questions about the role of natural gas in the region. Whether the industry grows will depend on how strongly states adopt energy efficiency and renewable sources of power and how citizens respond to new fracking and pipeline proposals. If the growing movement in western North Carolina is any indication, the future of fracking in Appalachia will be continue to be fraught with controversy.

Correction: This article has been updated to note that less than half of fracking fluids are withdrawn from wells after drilling — more than half remains underground.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment