Indian Trails of Appalachia

By Kathleen Marshall & Lamar Marshall

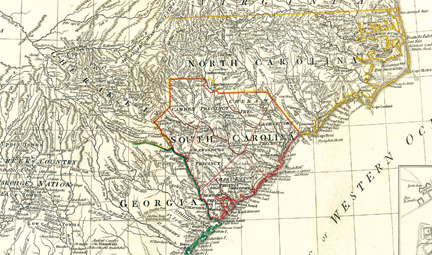

This map is a snapshot of the major trails and roads centered around western North Carolina in the late 18th Century. (A New and General Map of the Southern Dominion Belonging to the United States of America, Laurie & Whittle, London, 1794. Courtesy of the David Rumsey Collection)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Three hundred years ago the southern Appalachians were home to the sovereign Cherokee people. Over fifty towns and settlements were connected by a well-worn system of foot trails, many of which later became wagon roads built by Cherokee turnpike companies. This Indian trail system, which climaxed around 1800, was the blueprint for the basic circuitry of the region’s modern road and interstate system.

Stagnant European economies and the discovery of new natural resources sparked competitive world markets that led to wars between nations to procure land, gold, furs, and slaves from North America. By the 1700s, the British, French, and Spanish were fighting over what we call the Southeast.

The early Indian trails had evolved logically and inevitably— the result of thousands of years of Native Americans’ interactions with animals, tribal migration, relocations, population shifts, and lifestyle changes due to European contact and trade. They evolved within a landscape of obstacles and destinations, following corridors that combined efficiency with the path of least resistance.

Geological features were the key factors that led to the establishment and development of village sites and trail locations. Dividing ridges, passes and gaps, springs, river shoals, shallows, waterfalls, fords, and valleys all determined ultimately where trails and sometimes even tribal boundaries were established.

Travel routes considered good camping sites had springs and sometimes natural shelters, such as rock overhangs along bluffs.

In Europe, deerskins had become the material of choice for the “designer jeans” of the day. Fad and fashion in the streets of London were the beginning of the end of freedom for the Native Americans from whom we inherited our first road system. From the late 1690s on there was fierce competition between the French and the English to monopolize the trade of the Native Americans.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

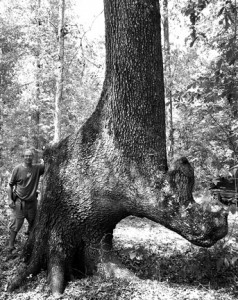

A remnant section of Gunter’s Landing trail near Wills Town Alabama used by 1100 Cherokee Indians in the Trail of Tears 1838. Rick West stands in the road for scale. Photo by Lamar Marshall

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The demand for deerskins would seduce the Indian tribes of Alabama and the Southeast into a dependency on manufactured European trade goods. The traditional industries and crafts that were the foundation of native economic freedom began to be abandoned. Pack trains leaving from Charles Town, South Carolina delivered manufactured European goods such as metal pots, cloth, knives, blankets, guns, powder balls, and rum. Traders returned laden with deer, beaver, bear, and other animal skins. Deerskins served as currency, and the value of a traded item was measured in deerskins. In 1732, a pistol traded for five buckskins or 10 doeskins, and a knife for two buckskins or four doeskins.

Cherokee Roads

The Cherokee world was divided into clusters of towns that were separated by mountain ranges. The Overhill Towns were located on the Tennessee River just south of Knoxville. Across the Unaka Mountains to the east were the Valley Towns of the Valley and Hiwassee Rivers, near Murphy in western North Carolina.

The Middle Towns lay along the Little Tennessee River north and south of the modern town of Franklin. Out Towns were located farther north and east along the Tuckasegee River in Swain and Jackson counties. The Lower Towns were located between Charles Town, South Carolina, and northern Georgia. An intricate trail network radiated out in every direction, connecting all the Cherokee towns and linking into a vast, continental Indian trail system.

In the mid-1700s, John Stuart listed fourteen Middle Towns, among which were Cowee and Nikwasi (also Nuqose, Nuquose) on the Little Tennessee River, north of present-day Franklin, North Carolina. The Middle Towns along the Little Tennessee River were destroyed by the English General Grant in 1761. Surviving Indians fled into the mountains and returned later to rebuild their homes. James Adair, in his History of the American Indians, wrote in 1775, “I have gathered good hops in the woods opposite Nuquose, where our troops were repelled by the Cheera-kee, in the year 1760. There is not a more healthful region under the sun, than this country; for the air is commonly open and clear, and plenty of wholesome and pleasant water . . . almost as transparent as glass.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

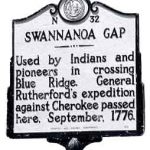

A marker on a trail near Swannanoa Gap, a major pass over the Blue Ridge Escarpment used by animals and native peoples for thousands of years. This trail served as a connecting gap for the Catawba River settlements and the Middle Towns of the Cherokee Nation. Photo by Lamar Marshall

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Wilderness Road

As treaties and cessions allowed the white planters and traders to inch their way to the escarpment of the Appalachians and Blue Ridge, Native Americans realized this mountain range was a natural boundary the white man must not pass. On the other side were Tennessee and Kentucky.

For a time, the Appalachian Mountains were an insurmountable obstacle to white expansion. But “hide hunters” like Daniel Boone and others coveted the buffalo and other game that abounded in the “Kaintucke” wilderness and the discovery of the Indian passage across the Cumberland Gap changed the course of history in British expansion in the Appalachians. In 1775, while in the employment of a land speculation company known as the Transylvania Company, Boone traveled from Fort Chiswell in Virginia, through the Cumberland Gap and into central Kentucky, often following Indian trails. The team of 35 loggers he led widened the trail through the Cumberland Gap, near the borders of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia. This became known as the Wilderness Road. From the Cumberland Gap to Flat Lick, Kentucky, Boone’s Trace followed a well established Indian trail. In the 1790s, the Wilderness Road was widened again to accommodate wagons. As a result, an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 white settlers poured through the Cumberland Gap before 1810.

The Great Warpath

Another principal artery was the Great Warpath, which connected the Gulf of Mexico with the Great Lakes. It skirted the Great Smoky Mountains on the western flank. Later, sections of it became the Federal Road in Tennessee. Ted Franklin Belue, noted in The Long Hunt, “Alabama Creeks hunkered along its bends to attack the Overhill Cherokees who lived in the Blue Ridge. The war road led to Long Island, in east Tennessee, then forked. One prong went past the Holston Valley to what is now Saltville, Virginia; the other cut into Pennsylvania.” As with other war roads, some of the trees along the Great Warpath were marked with blazes, and with arborglyphs smeared with red paint.

Indian Trails Today

Where these trails today remain natural and un-obliterated, old beech trees with carvings and trail marker trees might still be found nearby. Abandoned segments meander though fields and forests, and loops that followed the natural contours of the land can be found veering off of paved highways.

Today, it is not uncommon to find abandoned road banks that are 10 or 15 feet deep. A principal example is the Natchez Trace in Tennessee and Mississippi, yet there are perhaps thousands of remnants and hundreds of miles of preserved trails in the backwoods of Appalachia.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation estimates that only a small slice of about 2 million “cultural resources” that sit on 193 million acres managed by the U.S. Forest Service have been properly preserved. Yet many Indian trails on national forests, instead of being inventoried and studied, have been turned into collector roads for timber harvesting. These trails are a living nexus of cultural landmarks, and these trail-beds, along with their arborglyphs, rock cairns, bluff shelters, and ecological context must be preserved and studied. North Carolina and other states with significant quantities of public land in national forests contain the corridors and remnants of Indian trails. The historical corridors and remnants of these trails and roads should be identified, mapped, recorded, and their history preserved as a valuable element of Native American heritage. The historical landmarks of our ancestors are priceless and they are being eradicated even before we can identify them.

The cultural heritage department of Wild South, a non-profit conservation organization, is partnering with the Mountain Stewards and the Southeastern Anthropological Institute to work with the Eastern Band of the Cherokees to document the Cherokee Indian trail and road system. The project includes research, mapping, and the production of a comprehensive database with historical documentation integrated into Google Earth.

The Cherokee country of the 18th century was a magnificent mosaic of fully-functioning ecosystems that served as pharmacy, hardware, and grocery store.

These diverse ecosystems with their thousands of various plants, animals, and birds were veined with trails that were used not only for general travel, but for hunting, gathering food and medicine, for fishing and warring. The Southeastern Indian Trail System is a standing monument to the old ways, and should be preserved for future generations.

At the time this article was published, Lamar Marshall was Cultural Heritage Director for Wild South.

Related Articles

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

9 responses to “Indian Trails of Appalachia”

-

Much gratitude for sharing this information with the world. I am currently thru hiking the AT and it felt like much of what I have walked in Georgia has been travelled by people for millennia. Thank you!

-

I have seen a lot of these trees around. I like to wander through the woods and that’s when I see them.

-

The trail trees I have found point to a camp site and graves along the New River in a place called Raven’s Rock, a large 3-5 acre field beside a large bend in the river, my Dad use to take us camping there when I was a kid, the trail trees are on a ridge SW of the field, they are 1/4 mile from where I live now, I have found several came sites, and numerous artifacts at these sites, and what I think are 4 or 5 grave sites on a ridge, over looking the Raven’s Rock area, I go after a good rain and search, every time I go I find something new, I would love to do a dig at one of the sites, I’m positive that there are all kinds of good stuff still to be found.

-

Hey I would love to see these especially if there in the watauga or Ashe county area

-

I have photos of the trail trees I’ve found over the years, if you want them and the location’s I would be happy to send them to you.

-

I have found a few trail trees in Watauga Co.

-

There was a Tribe before Cherokee my Granma called them The Old Ones. What was the Tibe Name?

-

Dear Mr. Blackley,

Lamar Marshall, who originally wrote this article, is the Cultural Heritage Director for WildSouth.org and would definitely know the answer or know where you could find the answer. Best of luck with your search, we would also be curious to know what you find out!

Best regards,

Jamie Goodman

Editor, The Appalachian Voice -

Dear Sir/Ms, I’m curious to know if there were any Indian Trails passing through Elkin, North Carolina going west or north south? We are at the confluence of the Big Elkin Creek (know for two centuries as the Elkin River) and it was on land once owned by the father of Becky Boone, Daniel Boone’s father in law. There are a lot of arrowheads around here along the Yadkin River but no Indians and not much history. Can you direct me to some readings please. Best, Bill Blackley, MD

Leave a Comment